Translate this page into:

Anticandidal and anti-carcinogenic activities of Mentha longifolia (Wild Mint) extracts in vitro

⁎Corresponding author at: Botany and Microbiology Department, College of Science, P.O. Box 2455, Riyadh 11451, Saudi Arabia. ashraf812@yahoo.com (Ashraf A. Mostafa),

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Vulvovaginal candidiasis is a common health problem affecting about 75% of women at reproductive age. Teratogenicity and fetal toxicity resulting from antifungal therapy during pregnancy necessitates formulation of novel therapeutic agents. Disk diffusion method was performed to evaluate the antifungal activity of Mentha longifolia extracts against different candidal strains. Moreover, the anticancer activity of different M. longifolia extracts against MCF7 breast cancer cell line was evaluated by MTT assay. The M. longifolia n-hexane extract exhibited the highest antifungal activity, while the methanolic extract showed no antimicrobial activity against the tested Candida strains. Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of n-hexane extract was 250 µg/disk against C. tropicalis while it was 500 µg/disk against C. albicans and C. glabrata. Minimum fungicidal concentration (MFC) was 0.5 mg/disk against C. albicans and C. tropicalis, and 1 mg/disk against C. glabrata. GC–MS analysis of the n-hexane extract was performed to detect the active phytochemical components. Menthone (18.37%) was the main phytochemical active component of n-hexane extract followed by butyloctanol (16.13%), 1,5-(1-Bromo-1-methylethyl)-2-methyl-2-cyclohexen-1-one (14.89%), α-tocopherol (13.13%), eugenol (12.21%), α-resorcylamide (11.56%), citronellal (3.71%), butylated hydroxytoluene (3.21%), isocaryophyllene (2.81%), 2-hexyldecanol (2.12%) and tau-cadinol (1.87%). The methanolic extract exhibited the highest anticancer activity against MCF7 breast cancer cell line while diethyl ether extract exhibited the lowest activity with IC50 of 91.67 and 244.70 µg/ml respectively. M. longifolia extracts could be used as a potential source of novel anticandidal and anti-carcinogenic therapeutic agents.

Keywords

Vulvovaginal candidiasis

Mentha longifolia

Anti-candida

Minimum inhibitory concentration

Cytotoxicity

Phytochemicals

1 Introduction

Vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) is a frequent vaginal infection that commonly occurs among women of childbearing age (Adesiji et al., 2011; Gandhi et al., 2015). About 6–9% of women have suffered from recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis during their lifetime (Foxman et al., 2013). Candida albicans is the most frequent fungal pathogen, causing 85–95% of vaginal candida infections (Hong et al., 2014; Behzadi et al., 2015). Symptoms of VVC include: soreness, itching, burning, and abnormal vaginal discharge (Barousse et al., 2005). Apart from C. albicans, C. tropicalis and C. glabrata were reported as the most frequent strains associated to VVC (Jackson et al., 2005; Boatto et al., 2007; Mohanty et al., 2007; Rad et al., 2011). Virulence factors of Candida species that contributes to fungal pathogenicity include hyphal formation, biofilm formation, and extracellular hydrolytic enzyme production (Kumamoto and Vinces 2005; Ramage et al., 2009; Silva et al., 2012). Pregnant women are more susceptible to vaginal candida infections than non-pregnant women (Grigoriou et al., 2006; Ahmad and Khan 2009; Vijaya et al., 2014). Several researchers attributed the high infection rate of VVC among pregnant women to the high hormonal secretion that may promote yeast growth (Babić and Hukić 2010). However, treating pregnant women with antifungals is still challenging arised from the fetal toxicity and altered maternal pharmacokinetic parameters that may affect drug efficacy or increase toxicity to both the mothers and fetuses (Pilmis et al., 2014). There have been increasing reports stating that candida species, especially C. glabrata, have become resistant to different conventional antifungal drugs (Arendrup and Patterson 2017). Azole resistant strains were reported recently as a main cause of candidal infections (Whaley et al., 2017). Medicinal plants represent a potential source of novel therapeutic agents, being also the basis of indigenous healing systems, still widely used by the majority of populations in many countries (Malterud 2017). Mentha longifolia (L.) Huds. (family Lamiaceae) is a medicinal plant, commonly known as wild mint, that possess various pharmacological activities (Naghibi et al., 2010; Mokaberinejad et al., 2012). Previous studies have reported that M. longifolia extracts have a potential antimicrobial activity (Asekun et al., 2007; Gulluce et al., 2007). The essential oil of M. longifolia showed antifungal activity against C. albicans at a concentration of 7120 µg/ml (Mimica-Dukić et al., 2003). Such result was confirmed by Džamić et al., 2010 who reported that antifungal activity of the wild mint essential oil had minimum inhibitory (MIC) and minimum fungicidal (MFC) concentration values of 2.5 and 5 μl/ml, respectively. Natural products have been reported as a promising source for the production of novel anti-cancer therapeutic agents (Gordaliza 2007; Newman 2008).

Regarding to the high incidence of resistant candida strains and the teratogenic hazards of antifungal treatment during pregnancy, novel therapeutic agents for VVC are needed. The present study aimed to evaluate the antifungal efficiency of different M. longifolia extracts against the etiological agents of candidal vaginitis, investigate the anti-cancer activity of M. longifolia extracts against MCF-7 human breast cancer cell line and detect the phytoactive components of the different M. longifolia extracts.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Preparation of plant extracts

Leaves of M. longifolia were obtained from a local market in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Identification of plant material was performed by the Saudi herbarium of the Botany Department, College of Science, King Saud University, where vouchers were deposited (KSU_14683). Extraction procedure was performed using four organic solvents (diethyl ether, ethyl acetate, methanol and n-hexane) with different polarities to allow extraction of all phytochemical active components. Leaves of M. longifolia were disinfected using 0.5% sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl), washed using sterile distilled water for three consecutive times, and allowed to dry. Leaves were then macerated using a mechanical mortar to obtain a homogenous powder. 50 g of plant powder were soaked into four 500 mL Erlenmeyer flasks, each containing 200 mL of the four different organic solvents. Each flask was stirred over a magnetic stirrer at 25 °C for 48 h and then centrifuged at 9000 rpm for 10 min to get rid of plant residues. Supernatant of each solvent was filtered using Whatman filter paper no. 1 to attain clear filtrates. Finally, the clear filtrates were concentrated using a rotatory evaporator and kept at 4 °C until use. Calculation of the extract yields was carried out according to the following equation: Extract yield = (R/S) × 100;Where R is the weight of the plant extract residue and S is the weight of raw plant sample.

2.2 Fungal strains

Candidal strains (C. albicans, C. tropicalis and C. glabrata) were obtained from the culture collection of Botany and Microbiology Department, College of Science, King Saud University. The fresh inoculum was prepared by subculturing each Candida species onto Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA) medium at 35 °C for 48 h.

2.3 Preparation of candidal inocula

Previously prepared SDA slants were inoculated with different Candida species. The Candida specimens grown on the SDA slants were harvested using a sterile saline solution. The absorbance of microbial suspension was adjusted at 560 nm using a spectrophotometer to obtain a viable cell count of 107 colony forming unit (CFU)/mL for each Candida species.

2.4 Screening of the antifungal activity of different M. longifolia extracts

The disk diffusion method was performed to evaluate the antifungal activity of different M. longifolia extracts against different Candida strains. M. longifolia extracts were screened for their anticandidal activity in which 15 mL of SDA medium was poured into sterile petri dishes (base layer) followed by 10 mL of SDA containing a Candida suspension (1 mL of Candida for each 100 mL of medium to obtain a viable cell count of 105 CFU/mL). Sterile filter paper disks (8 mm in diameter) were loaded with 10 mg of M. longifolia extracts then placed over the seeded layer once it had solidified (Mansourian et al., 2014; Mostafa et al., 2018). Fluconazole antifungal drug was used as a positive control with a concentration of 25 µg/disk according to the Clinical & Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI, 2007). Fungal susceptibility to fluconazole, as an antifungal drug, was determined based on the inhibition zone diameter as follows: for C. albicans and C. tropicalis, a diameter ≥19 mm was interpreted as sensitive, 15–18 mm as dose dependent, and ≤14 mm as resistant; while for C. glabrata, a diameter ≥15 mm was interpreted as dose dependent, and finally a diameter ≤14 mm was interpreted as resistant. Plates were incubated at 4 °C for 2 h to allow the M. longifolia extracts to diffuse throughout the medium. Finally, plates were incubated at 35 °C for 48 h and the inhibition zone diameter was measured using Vernier caliper. Inhibition zone diameters were recorded and considered as an indication of antifungal efficiency of the mint extracts against different candidal pathogens.

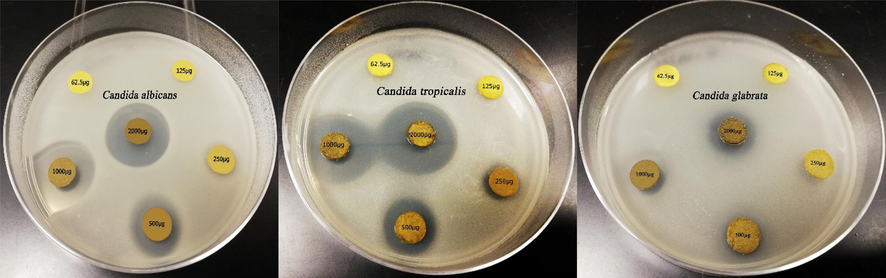

2.5 Determination of the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC)

The lowest concentration of M. longifolia extract exhibiting anticandidal activity was identified as the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC). The MIC was evaluated for the n-hexane extract of M. longifolia as it showed the highest antimicrobial efficiency. For such, 15 mL of SDA medium was poured into sterile petri dishes (base layer) and 10 mL of seeded SDA was poured on top and left to solidify. Sterile filter paper disks (8 mm in diameter) with different concentration of n-hexane extracts of M. longifolia (62.5, 125, 250, 500, 1000, 2000 µg/disk) were placed over the seeded medium. Plates were stored at 5 °C for 2 h to allow the mint extracts to diffuse. Finally, plates were incubated at 35 °C for 48 h and the inhibition zone diameters were measured. MIC was recorded for the different Candida strains tested.

2.6 Determination of the minimum fungicidal concentration (MFC)

The lowest concentration of the M. longifolia n-hexane extract in which pathogens show no growth is defined as MFC. Freshly prepared SDA plates were inoculated with streaks taken from the inhibition zone area of the MIC and the two successive concentrations. Plates were then incubated at 35 °C for 48 h and examined for candidal growth. The lowest concentration of the n-hexane extract of M. longifolia showing no Candida growth was recorded as the minimum fungicidal concentration (MFC).

2.7 Cytotoxicity assay

Human breast cancer (MCF7) cell lines were obtained from the collection of the zoology department, college of science, King Saud University, Saudi Arabia. The anti-cancer activity of Mentha longifolia (diethyl ether, ethyl acetate, methanolic and n-hexane) extracts against MCF7 cell lines was evaluated using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay (Famuyide et al., 2019). The cells were cultured in minimal essential medium (MEM, Highveld Biological, South Africa) supplemented with 0.1% gentamicin (Virbac) and 5% foetal calf serum (Adcock-Ingram) in a 5% CO2 incubator. Incubation of MCF7 cells in 96-well plate at 37 °C for 24 hr. in 5% CO2 incubator to allow adherence of cells. The crude M. longifolia extracts were dissolved in methanol (10 mg/mL), and appropriate dilutions were prepared. MCF7 cells were treated with the M. longifolia extracts at concentration range of (0.0065–1 mg/ml). After a 48hr exposure, removal of supernatant was performed and MTT solution was added to the wells at a concentration of 5 mg/ml. Incubation of plates at 37 °C for 4 hr and then supernatants were removed. Finally, 50 μl of DMSO was added to the wells to allow the solubilization of the formed formazan crystals. Absorbance was measured at wavelength of 570 nm. The concentration causing 50% inhibition of cell viability (IC50) was calculated.

2.8 Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) of M. longifolia extracts

Phytochemical analysis of the extracts was carried out using (an Agilent 7890 gas chromatograph and an Agilent 5975C Mass Spectrometer, USA) to investigate the phytochemical active components of different M. longifolia extracts. The gas chromatograph was set as follows: a HP-5MS UI capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm; 0.25 μm film thickness), helium carrier gas with a flow rate of 1 mL/min, an oven temperature of 40 °C and adjusted to 250 °C at 5 °C/min, an injection volume of 1 μl, injector and detector temperatures of 250 °C, and a split ratio of 1:50. The mass spectrometry was set as follows: an ionization potential of 70 eV, a mass range from 40 to 400 amu, and an electron multiplier energy of 2000 V. Identification of the phytochemical components of leaf extracts of M. longifolia was determined by comparing the results of the GC–MS analysis with the reference retention time and spectral mass data of the NIST database.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Extract yields

The highest yield of M. longifolia extracts was obtained using methanol (5.49%) as solvent, followed by diethyl ether (3.82%), ethyl acetate (1.27%), and n-hexane (0.29%).

3.2 Antifungal activity

In our current study, C. albicans strain expressed resistance to fluconazole and that was coincident with the results reported by Nasrollahi et al., (2015) in which 94% of C. albicans strains isolated from vaginitis patients were resistant. Moreover, the resistance of C. glabrata strain to fluconazole drug was detected and the previous result was similar to that of Hasanvand et al., (2017) who reported the fluconazole resistance of three C. glabrata strains isolated from vaginitis patients.

Screening of the antifungal potency of ethyl acetate, diethyl ether and n-hexane extracts of M. longifolia exhibited a high efficiency at concentration of 10 mg/disc against different candidal strains with different susceptibility patterns. The M. longifolia extract using n-hexane as a solvent showed the highest antifungal activity against C. albicans, C. glabrata, and C. tropicalis, with inhibition zone diameters of 27.43, 16.33, and 22.63 mm, respectively (Table 1). These results were in accordance with that of Carretto et al. (2010) who proved the antimicrobial activity of Mentha sp. against Candida strains at concentration range of 7.8–250 mg/ml with inhibition zone diameters ranging from 5 to 10 mm.

M. longifolia extracts

(10 mg/disc)Inhibition zone diameter (mm) of Candida pathogens

C. albicans

C. glabrata

C. tropicalis

Diethyl-ether extract

14.93 ± 0.15

12.17 ± 0.14

21.67 ± 0.43

Ethyl acetate extract

13.43 ± 0.32

13.20 ± 0.23

16.57 ± 0.49

Methanolic extract

0.0 ± 0.00

0.0 ± 0.00

0.0 ± 0.00

N-hexane extract

22.63 ± 0.67

16.33 ± 0.29

27.43 ± 0.32

Fluconazole (25 μg/disc)

13.77 ± 0.31

9.67 ± 0.42

23.87 ± 0.37

On the other hand, the methanolic extracts of M. longifolia exhibited no antifungal activity against the three Candida strains which was ascertained by Gulluce et al., (2007) who found that methanolic extracts of M. longifolia leaves have no antimicrobial activity against C. albicans. In contrast, the diethyl ether extract of M. longifolia showed high antifungal activity against all three Candida strains with inhibition zone diameters of 14.93, 12.17, and 21.67 mm for C. albicans, C. glabrata, and C. tropicalis, while a moderate efficacy was detected for the ethyl acetate extract against the tested strains with inhibition zone diameters of 13.43, 13.20, and 16.57 mm respectively. Furthermore, the antifungal activity of the n-hexane extract of M. longifolia against non-albicans strains (C. glabrata and C. tropicalis) was significantly higher (p < 0.05) than that of fluconazole (control).

3.3 Determination of the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of the M. longifolia n-hexane extract

The n-hexane extract of M. longifolia was the most effective extract against the concerned Candida strains and its MIC against C. albicans was 500 µg/disk, a value lower than that previously ascertained by Bakht et al., (2014) who reported MIC value by 2 mg/disk. MIC of n-hexane extract against non-albicans strains (C. tropicalis and C. glabrata) was 250 and 500 µg/disk respectively (Table 2). MIC results confirmed that C. tropicalis exhibited the highest sensitivity to the n-hexane extract of M. longifolia (Fig. 1).

Concentration of plant extract (µg/disc)

Inhibition zone diameter (mm) of Candida strains

C. albicans

C. glabrata

C. tropicalis

62.5

0.00 ± 0.00

0.00 ± 0.00

0.00 ± 0.00

125

0.00 ± 0.00

0.00 ± 0.00

0.00 ± 0.00

250

0.00 ± 0.00

0.00 ± 0.00

11.40 ± 0.17

500

13.17 ± 0.28

9.63 ± 0.07

15.38 ± 0.23

1000

17.27 ± 0.24

12.35 ± 0.32

21.65 ± 0.26

2000

20.97 ± 0.12

14.25 ± 0.20

23.97 ± 0.27

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of the Mentha longifolia n-hexane extract against the three Candida pathogens tested.

3.4 Determination of the minimum fungicidal concentration (MFC) of the M. longifolia n-hexane extract

The n-hexane extract of M. longifolia was tested for MFC against the three Candida strains used in order to detect the lowest concentration of the extract that shows no fungal growth. The minimum fungicidal concentration was achieved at 0.5 mg/disk against C. albicans and C. tropicalis while it was 1 mg/disk against C. glabrata. These results were contrasted with the previous study which reported the fungicidal activity of Mentha sp. extract at concentration range of 0.5–8 μl/mL against Candida pathogens (Saharkhiz et al., 2012).

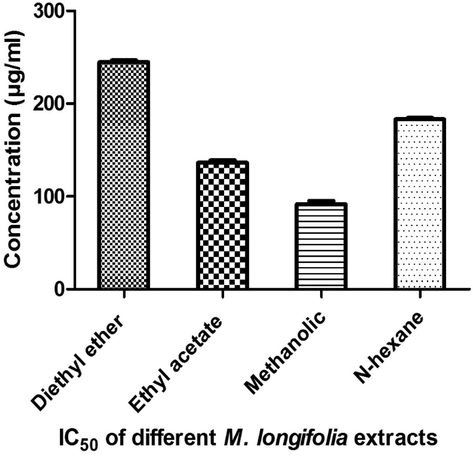

3.5 Cytotoxicity assay

Methanolic extract exhibited the highest cytotoxic activity against MCF7 breast cancer cell line with IC50 of 91.67 µg/ml (Fig. 2). Our results were in accordance with that of Al-Ali et al., (2013) who reported that the methanolic extract of M. longifolia possess potential anti-cancer activity against MCF7 cell line at concentration range of 20–320 µg/ml. Diethyl ether extract exhibited the lowest activity against MCF7 cell line with IC50 of 244.7 µg/ml. Moderate cytotoxic activities of ethyl acetate and n-hexane extracts were detected with IC50 of 136.3 and 183.2 µg/ml respectively. Our results were in accordance with that of Sharma et al. (2014) who reported the anticancer activity of Mentha sp. extracts against eight human (breast, colon, glioblastoma, lung, leukemia and prostate) cancer cell lines. Stringaro et al. (2018) ascertained that Mentha spp. extracts were a potential source of novel anticancer agents due to their high activity against different cancer cell lines.

IC50 of different M. longifolia extracts against MCF7 cancer cell line.

3.6 GC–MS analysis of M. longifolia extracts

Phytochemical analysis of the M. longifolia n-hexane extract exhibiting the highest anticandidal activity showed that menthone (18.37%) was the main phytochemical active component followed by butyloctanol (16.13%), 1,5-(1-bromo-1-methylethyl)-2-methyl-2-cyclohexen-1-one (14.89%), α-tocopherol (13.13%), eugenol (12.21%), α-resorcylamide (11.56%), citronellal (3.71%), butylated hydroxytoulene (3.21%), isocaryophyllene (2.81%), 2-hexyldecanol (2.12%), and tau-cadinol (1.87%) (Table 3). These components were similar to that reported by Okut et al. (2017) who reported that the chemical composition of M. longifolia extract was compromised of Menthone as a predominant chemical constituent (19.31%) followed by Pulegone (12.42%), Piperitone (11.05%), Dihydrocarvon (8.32%), Limonene (6.1%), 3-Terpinolenone (5.66%), 1,8-Cineole (4.37%), Germacrene D (3.38%) and Caryopyllene (3.19%), respectively. Other study reported that wild mint oil was mainly composed of menthone (34.13%) (Salman et al., 2015). Variation in the chemical composition of wild mint between our findings and previous studies may be attributed to a variety of factors, such as geographic variation, harvest time, environmental and agronomic conditions, the botanical parts of plants, and extraction methods (Kurihara et al., 2003; Fang et al., 2011; Xi et al., 2014; Bessada et al.,2016; Liu et al., 2016).

Compounds

Chemical formula

M.W

RT

% of Total

Menthone

C10H18O

154.16

4.699

18.37

Citronellal

C10H18O

182.30

4.911

3.71

α-Resorcylamide

C7H7NO3

154.25

6.433

11.56

1,5-(1-Bromo-1-methylethyl)-2-methyl-2-cyclohexen-1-one

C10H15BrO

153.14

8.604

14.89

Eugenol

C10H12O2

245.16

8.923

12.21

Isocaryophyllene

C15H24

164.20

10.508

2.81

Butylated Hydroxytoulene

C15H24O

204.36

12.681

3.21

T-cadinol

C15H26O

222.37

16.130

1.87

Butyloctanol

C12H26O

290.50

26.829

16.13

α-Tocopherol

C29H50O2

224.34

32.707

13.12

2-Hexyldecanol

C16H34O

376.6

35.794

2.12

The reported potential antimicrobial activity of M. longifolia can be attributed to the presence of oxygenated monoterpenes in their phytochemical compounds (Mimica-Dukić et al., 2003; Şahin et al., 2003). However, Samber et al. (2015) reported that the main phytochemical components of Mentha sp. essential oil are menthone and carvone, and both of them act as antifungal agents due to their effect on ergosterol of cell membrane biosynthesis leading to microbial cell death.

Moreover, the diethyl ether extract of M. longifolia that exhibited a moderate anticandidal activity against the tested strains was composed of 3,5-dihydroxybenzamide (42.89%) as a main phytoactive component, followed by 5-(7a-isopropenyl-4,5-dimethyl-octahydroinden-4-yl)-3-methyl-pent-2-en-1-ol (11.03%), isoledene (10.91%), butylated hydroxytoluene (9.20%), epizonarene (4.92%), lycopersen (5.27%), epizonarene (4.92%), pyrrolo [3,2-d]pyrimidin-2,4(1H,3H)-dione (3.69%), naphthalene,1,1/-(1,10-decanediyl)bis*decahydro (3.37%), 1,1-naphthyl isocyanide (2.84%), benzenemethanol,3-hydroxy-5-methoxy- (2.09%), phosphinic acid, diisopropyl-,menthyl ester (1.89%), and phytol acetate (1.89%) (Table 4).

Compounds

Chemical formula

M.W

RT

% of Total

Benzenemethanol,3-hydroxy-5-methoxy-

C8H10O3

154.16

4.891

2.09

Phosphinic acid, diisopropyl-,menthyl ester

C16H33O2P

288.41

5.141

1.89

Naphthalene,1,1/-(1,10-decanediyl)bis*decahydro

C30H54

414.70

5.211

3.37

3,5-Dihydroxybenzamide

C7H7NO3

153.14

6.978

42.89

1,1-Naphthyl isocyanide

C11H7N

153.18

7.410

2.84

Pyrrolo[3,2-d]pyrimidin-2,4(1H,3H)-dione

C6H5N3O2

151.12

9.240

3.69

Lycopersen

C40H66

547.00

10.940

5.27

Butylated Hydroxytoluene

C15H24O

220.35

12.959

9.20

Isoledene

C15H24

204.36

13.067

10.91

Epizonarene

C15H24

204.36

16.544

4.92

5-(7a-isopropenyl-4,5-dimethyl-octahydroinden-4-yl)-3-methyl-pent-2-en-1-ol

C20H34O

290.50

27.120

11.03

Phytol acetate

C22H42O2

338.57

34.075

1.89

The M. longifolia ethyl acetate extract that exhibited a moderate antifungal activity against the concerned Candida strains whose GC–MS analysis showed that piperitone (15.75%), menthone (15.28%), and citronellal (14.87%) were the main active components (Table 5). Other study attributed the potent anticandidal activity of M. longifolia to their constituents of citronellal which could be used as a chemotherapeutic agent for the treatment of VVC or RVVC (Medeiros et al., 2017). The n-hexane and ethyl acetate extracts of M. longifolia were rich in menthone with percentage of 18.37% and 15.28% respectively. Menthone is a phenolic monoterpene that was reported to possess hydrophobic characteristics causing disruption of microbial selective permeability through its incorporation into microbial cell membranes (Saharkhiz et al., 2012).

Compounds

Chemical formula

M.W

RT

% of Total

3-Hepten-2-one, 3-ethyl-4-methyl-

C10H18O

154.25

4.891

4.04

Menthone

C10H18O

154.25

4.991

15.28

Citronellal

C10H18O

154.25

5.103

14.87

Endo-3-acetamido camphor

C10H18O

154.25

6.806

7.02

Piperitone

C10H16O

152.23

6.847

15.75

Pyrrolo[3,2-d]pyrimidin-2,4(1H,3H)-dione

C6H5N3O2

151.12

8.822

14.80

Menthol crotonate

C14H24O2

224.33

10.636

1.71

Isoledene

C15H24

204.36

12.018

4.97

γ-Muurolene

C15H24

204.36

12.820

3.78

T-Cadinol

C15H26O

222.36

16.223

9.95

5-[7a-Isopropenyl-4,5-dimethyl-octahydroinden-4-yl]-3-methyl-pent-2-en-1-ol

C21H44O3S

376.60

26.887

7.82

The methanolic extract of M. longifolia exhibited the highest cytotoxic activity against MCF7 breast cancer cell line so can be used as a potential source of novel anticancer therapeutic agents. The main phytoactive compounds of methanolic extract were caryophyllene, t-cadinol, menthone, eugenol and menthol crotonate (Table 6). The potential anti-cancer activity of M. longifolia extracts may be attributed to their constituents of eugenol which possess the ability to induce apoptosis against the cancer cells Jaganathan and Supriyanto (2012).

Compounds

Chemical formula

M.W

RT

% of Total

Menthone

C10H18O

154.25

4.777

9.36

Decalin,1-methoxymethyl-

C12H22O

182.30

4.995

5.29

Isothujol

C10H18O

154.25

5.358

6.62

3,5-Dihydroxybenzamide

C7H7NO3

152.23

6.648

22.33

2-Adamantanol,2-(bromomethyl)-

C11H17BrO

245.16

8.819

7.98

Eugenol

C10H12O2

164.20

9.022

6.09

Caryophyllene

C15H24

204.36

10.541

11.30

T-Cadinol

C15H26O

222.36

16.206

10.72

5-(7a-Isopropenyl-4,5-dimethyl-octahydroinden-4-yl)-3-methyl-pent-2-en-1-ol

C20H34O

290.50

26.862

6.56

Menthol crotonate

C14H24O2

224.34

29.768

5.51

Sulfurous acid, hexyl pentadecyl ester

C21H44O3S

376.60

30.959

8.22

4 Conclusions

Mentha longifolia extracts can be considered as a potential source of natural antifungal drugs where the tested extracts showed a highly antifungal potency- against fluconazole resistant strains like C. albicans and C. glabrata. Hexanic extract of M. longifolia exhibited the highest antifungal activity against all tested candidal strains compared with the other solvents. Moreover, these solvent extracts of M. longifolia were found to possess a potent anticancer activity against MCF7 human breast cancer cell line. The potential anti-Candida and anti-Cancer activities of M. longifolia extracts may be attributed to their chemical constituents of phytoactive components such as menthone, citronellal and eugenol. From the all solvent extracts, methanolic extract showed the highest cytotoxic activity against human breast cancer cells. Results of the anticandidal and anticancer activities highlight the potential of utilizing these extracts as a safe and effective antifungal and anti-cancer therapeutic agents.

Acknowledgement

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research in King Saud University for funding this work through research group No. (RGP-1440-094).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Isolation and antifungal sensitivity to Candida isolates in young females. Open. Med.. 2011;6(2):172-176.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of Candida species and potential risk factors for vulvovaginal candidiasis in Aligarh, India. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. X. 2009;144(1):68-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytotoxic activity of methanolic extract of Mentha longifolia and Ocimum basilicum against human breast cancer. Pak. J. Biol. Sci.. 2013;16(23):1744-1750.

- [Google Scholar]

- Multidrug-resistant Candida: epidemiology, molecular mechanisms, and treatment. J. Infect. Dis.. 2017;216(suppl_3):S445-S451.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of drying methods on the quality and quantity of the essential oil of Mentha longifolia L. subsp. Capensis. Food Chem.. 2007;101(3):995-998.

- [Google Scholar]

- Candida albicans and non-albicans species as etiological agent of vaginitis in pregnant and nonpregnant women. Bosnian J. Basic Med. Sci.. 2010;10(1):89.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial potentials of Mentha longifolia by disc diffusion method. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci.. 2014;27(4)

- [Google Scholar]

- Vaginal epithelial cell anti-Candida albicans activity is associated with protection against symptomatic vaginal candidiasis. Infect Immun.. 2005;73(11):7765-7767.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phenolic profile and antioxidant activity of Coleostephus myconis (L.) Rchb. f.: an underexploited and highly disseminated species. Ind. Crops Prod.. 2016;89:45-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Correlação entre os resultados laboratoriais e os sinais e sintomas clínicos das pacientes com candidíase vulvovaginal e relevância dos parceiros sexuais na manutenção da infecção em São Paulo, Brasil. Rev. Bras. Ginecol. Obstet.. 2007;29(2):80-84.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial activity of Mentha piperita L. against Candida spp. Braz. Dent. Sci.. 2010;13(1/2):4-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- CLSI, 2007. Zone diameter interpretative standards, corresponding minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) interpretative breakpoints, and quality control limits for antifungal disk diffusion susceptibility testing of yeasts: informational supplement. CLSI document M44-S2 Clinical & Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA.

- Antifungal and antioxidant activity of Mentha longifolia (L.) Hudson (Lamiaceae) essential oil. Bot. Serb.. 2010;34(1):57-61.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antibacterial and antibiofilm activity of acetone leaf extracts of nine under-investigated south African Eugenia and Syzygium (Myrtaceae) species and their selectivity indices. BMC Complement Altern. Med.. 2019;19(1):141.

- [Google Scholar]

- Provenance and temporal variations in selected flavonoids in leaves of Cyclocarya paliurus. Food Chem.. 2011;124(4):1382-1386.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis in 5 European countries and the United States: results from an internet panel survey. J. Low Genit. Tract. Dis.. 2013;17(3):340-345.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antifungal susceptibility of Candida against six antifungal drugs by disk diffusion method isolated from vulvovaginal candidiasis. Int. J. Curr. Res. Rev.. 2015;7(11):20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Natural products as leads to anticancer drugs. Clin. Transl. Oncol.. 2007;9(12):767-776.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of clinical vaginal candidiasis in a university hospital and possible risk factors. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol.. 2006;126(1):121-125.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial and antioxidant properties of the essential oils and methanol extract from Mentha longifolia L. ssp. longifolia. Food Chem.. 2007;103(4):1449-1456.

- [Google Scholar]

- Molecular epidemiology and in vitro antifungal susceptibility of candida isolates from women with vulvovaginal candidiasis in northern cities of Khuzestan province, Iran. Jundishapur J Microbiol.. 2017;10(8)

- [Google Scholar]

- Vulvovaginal candidiasis as a chronic disease: diagnostic criteria and definition. J. Low Genit. Tract. Dis.. 2014;18(1):31-38.

- [Google Scholar]

- The epidemiology of mycotic vulvovaginitis and the use of antifungal agents in suspected mycotic vulvovaginitis and its implications for clinical practice. West Indian Med. J.. 2005;54(3):192-195.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antiproliferative and molecular mechanism of eugenol-induced apoptosis in cancer cells. Molecules. 2012;17(6):6290-6304.

- [Google Scholar]

- Contributions of hyphae and hypha-co-regulated genes to Candida albicans virulence. Cell Microbiol.. 2005;7(11):1546-1554.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hypolipemic effect of Cyclocarya paliurus (Batal) Iljinskaja in lipid-loaded mice. Biol. Pharm. Bull.. 2003;26(3):383-385.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of light regime and provenance on leaf characteristics, growth and flavonoid accumulation in Cyclocarya paliurus (Batal) Iljinskaja coppices. Bot. Stud.. 2016;57(1):28.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ethnopharmacology, chemistry and biological properties of four Malian medicinal plants. Plants. 2017;6(1):11.

- [Google Scholar]

- The comparative study of antifungal activity of Syzygium aromaticum, Punica granatum and nystatin on Candida albicans; an in vitro study. J. Mycol. Med.. 2014;24(4):e163-e168.

- [Google Scholar]

- Study of the antifungal potential of (r)-(+)-citronellal and its association with therapeutic agents used in the treatment of vulvovaginal candidiasis. Biosci. J.. 2017;33(2)

- [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of three Mentha species essential oils. Planta Med.. 2003;69(05):413-419.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence & susceptibility to fluconazole of Candida species causing vulvovaginitis. Indian J. Med. Res.. 2007;126(3):216.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mentha longifolia syrup in secondary amenorrhea: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trials. DARU J. Pharm. Sci.. 2012;20(1):97.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial activity of some plant extracts against bacterial strains causing food poisoning diseases. Saudi J. Biol. Sci.. 2018;25(2):361-366.

- [Google Scholar]

- Labiatae family in folk medicine in Iran: from ethnobotany to pharmacology. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. 2010:63-79.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fluconazole resistance Candida albicans in females with recurrent Vaginitis and Pir1 overexpression. Jundishapur J. Microbiol.. 2015;8(9)

- [Google Scholar]

- Natural products as leads to potential drugs: an old process or the new hope for drug discovery? J. Med. Chem.. 2008;51(9):2589-2599.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chemical composition of essential oil of Mentha longifolia L. Subsp. Longifolia growing wild. Pak. J. Bot. 2017;49(2):525-529.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antifungal drugs during pregnancy: an updated review. J. Antimicrob. Chemother.. 2014;70(1):14-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- The epidemiology of Candida species associated with vulvovaginal candidiasis in an Iranian patient population. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol.. 2011;155(2):199-203.

- [Google Scholar]

- Our current understanding of fungal biofilms. Crit. Rev. Microbiol.. 2009;35(4):340-355.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chemical composition, antifungal and antibiofilm activities of the essential oil of Mentha piperita L. ISRN Pharm.. 2012;2012

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of antimicrobial activities of Satureja hortensis L. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 2003;87(1):61-65.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chemical composition for hydrodistillation essential oil of Mentha longifolia by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry from north regions in Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Pharm. Chem.. 2015;7:34-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synergistic anti-candidal activity and mode of action of Mentha piperita essential oil and its major components. Pharm. Biol.. 2015;53(10):1496-1504.

- [Google Scholar]

- In vitro anticancer activity of extracts of Mentha spp. against human cancer cells. Indian J. Biochem. Biol.. 2014;55:416-419.

- [Google Scholar]

- Candida glabrata, Candida parapsilosis and Candida tropicalis: biology, epidemiology, pathogenicity and antifungal resistance. FEMS Microbioll Rev.. 2012;36(2):288-305.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antioxidant, antifungal, antibiofilm, and cytotoxic activities of Mentha spp. essential oils. Medicines. 2018;5(4):112.

- [Google Scholar]

- Azole antifungal resistance in Candida albicans and emerging non-albicans Candida species. Front Microbiol.. 2017;7:2173.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phenolic composition of Chinese wild mandarin (Citrus reticulata Balnco.) pulps and their antioxidant properties. Ind. Crops Prod.. 2014;52:466-474.

- [Google Scholar]