Anti-aggregation potential of polyphenols from Ajwa date palm (Phoenix dactylifera): An in-silico analysis

⁎Corresponding authors. qamarbiotech@gmail.com (Qamar Zia), mrehman@ksu.edu.sa (Md Tabish Rehman),

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background

Amyloid β (Aβ) fibril agglomeration is crucial in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) etiology, leading to significant harm to the central nervous system. Polyphenols have been investigated for their capacity to hinder Aβ agglomeration.

Objective

This investigation aimed to assess the potential of Ajwa date palm (Phoenix dactylifera)-based bioactives in binding and disrupting resilient Aβ1-42 fibrils through in-silico studies.

Methods

The primary phytochemicals present in date palms were subjected to molecular docking with three different conformers of Aβ1-42 and Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) analysis. The stability of the system was assessed through molecular dynamics (MD) simulation.

Results

It was noted that Diosmetin, Rutin, and Genistein effectively bind with 2BEG, 2MXU, and 2NAO fibrils, respectively, with docking energies ranging from −7.2 to −8.2 kcal/mol. Diosmetin, Rutin, and Genistein show notable pharmacokinetic variability, with LogP values from −1.69–2.58, with 1–6 rotatable bonds, and total polar surface areas (TPSA) between 112.52 and 240.90 Å2, characteristics important for drug candidacy evaluation. Their ADMET properties include solubility values of −3.238 to −3.595 mol/L, intestinal absorption of 23.4–93.4%, and VDss ranging from 0.094 to 1.663 L/kg. The ensuing MS simulations spanning 100 ns, illuminated the establishment of a robust peptide-chemical complex. Hydrophobic interactions, ionic and hydrogen bonds play a critical role in the ligand binding with their respective targets.

Conclusions

These findings underscore the potential of these botanicals as leads for developing potent Aβ agglomeration inhibitors. However, before introducing into clinical settings, these findings need to be validated further.

Keywords

Alzheimer’s disease

Ajwa dates

Polyphenols

Molecular docking

Molecular Dynamics

- AD

-

Alzheimer’s disease

- Aβ

-

Amyloid β

- ADT

-

AutoDock Tools

- CGenFF

-

CHARMM General Field

- GROMACS

-

Groningen Machine for Chemical Simulations

- Kd

-

Dissociation coefficient

- LGA

-

Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm

- MD

-

Molecular dynamics

- MMFF

-

Merck Molecular Force Field

- Rg

-

Radius of gyration

- RMSD

-

Root-mean-square deviation

- SASA

-

Solvent accessible surface area

- UFF

-

Universal Force Field

- ΔG

-

Binding energy

- APP

-

Amyloid precursor protein

- TPSA

-

Total polar surface areas

- VDs

-

Volumes of distribution

- Fu

-

Fraction unbound

- ADMET

-

Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity

- AGEs

-

Advanced Glycation End Products

- ROS

-

Reactive oxygen species

Abbreviations

1 Introduction

The precise mechanisms that initiate and drive the progression of Alzheimer's disease (AD) remain elusive. Among the clinical hallmarks of AD is the misfolding of agglomerated β-Amyloid (Aβ) proteins and their subsequent accumulation in neurons (Itoh et al., 2022). These aggregated Aβ peptides further organize into different oligomers of cross-β-sheet fibrils, a process that generates extrinsically insoluble plaques (Kurkinen et al., 2023). The formation of these senile aggregates is primarily driven by Aβ1-40 fibrils, although Aβ1-42 species are particularly toxic due to their inherent propensity to self-assemble (Abedin et al., 2021).

Botanicals have been a cornerstone of traditional medicine for centuries. Numerous studies highlight the potential of phytochemicals, particularly polyphenols, in addressing neurological conditions like AD (Muscat et al., 2020). These antioxidants can potentially impede Alzheimer's progression by inhibiting amyloid fibril formation (Sinyor et al., 2020). Date palm trees (Phoenix dactylifera L.), significant in Egyptian and Middle Eastern pharmacopeia, have versatile medicinal uses (Anwar et al., 2022). The Ajwa cultivar, indigenous to Saudi Arabia, contains sugars, minerals, vitamins, and various bioactive substances. Traditionally, Ajwa dates are valued for their anti-oxidative, anti-microbial, anti-inflammatory, hepatoprotective, anti-cancer, and cardiovascular benefits (Aljuhani et al., 2019; Fernández-López et al., 2022).

Machine learning and computational tools represent cutting-edge methods for discovering pharmaceutical agents from botanical sources for managing AD. Molecular simulations predict binding affinities and interactions between compounds and AD-related target proteins, aiding in the identification of promising lead molecules (Gupta and Dasmahapatra, 2020). In a previous study, we investigated the effect of date fruit botanicals on Aβ1-40 fibrils (Zia et al., 2022). However, it is known that the main culprits in AD are Aβ1-42 fibrils. Thus, our current research focuses on the anti-amyloidogenic properties of phytonutrients from date palms against Aβ1-42 fibrils using in-silico methods. We performed docking analysis to identify optimal ligands and used molecular dynamics to assess their binding affinity and stability. We used three distinct conformers of Aβ1-42 to gain insights into the binding interactions between the botanicals and the fibril. Understanding the binding affinities of ligands for each conformer of the Aβ protein can help design targeted therapeutics for AD.

2 Methodologies

2.1 Preparation of proteins and ligands

The 3-D coordinates of target peptides (2BEG: 3D structure of Aβ1-42 proto-filament, 2MXU: a S-shaped 42-residue β-amyloid dodecamer, and 2NAO: a disease-relevant Aβ1-42 amyloid fibril) were acquired from the PDB RCSB database (https://www.rcsb.org). AutoDock Tools (ADT) (https://autodocksuite.scripps.edu/adt/) was employed to prepare protein for molecular docking by adding Kollman charges. It should be noted that there no water molecules and heteroatoms in the structure file of target proteins. Finally, Merck Molecular Force Field (MMFF) was used to reduce the energy of protein molecules. The 2D structures of ligands were downloaded from PubChem (Table 1) (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Ligands were optimized for docking process by designating bond ordering and degrees using ADT. The component charges of Gasteiger were established. Universal Force Field (UFF) was employed to minimize the energy levels of the selected ligands using PyRx (https://pyrx.sourceforge.io).

| S. No. | Ligand | ID Number | Formula | Docking Energy (kcal/mol) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2BEG | 2MXU | 2NAO | ||||

| 1. | Apigenin | 5,280,443 | C15H10O5 | −6.3 | −7.2 | −7.4 |

| 2. | Cianidanol | 9064 | C15H14O6 | −6.3 | −6.8 | −6.9 |

| 3. | Daidzein | 5,281,708 | C15H10O4 | −5.7 | −6.8 | −6.9 |

| 4. | Diosmetin | 5,281,612 | C16H12O6 | −7.2 (−7.9)* | −7.4 (−7.8)* | −6.2 (−7.7)* |

| 5. | Ferulic acid | 445,858 | C10H10O4 | −6.0 | −5.3 | −5.4 |

| 6. | Formononetin | 5,280,378 | C16H12O4 | −6.7 | −7.1 | −6.9 |

| 7. | Gallic acid | 370 | C7H6O5 | −4.7 | −4.9 | −5.1 |

| 8. | Genistein | 5,280,961 | C15H10O5 | −6.2 (−7.6)* | −6.8 (−8.1)* | −8.0 (−7.9)* |

| 9 | Glycitein | 5,317,750 | C16H12O5 | −6.2 | −7.2 | −7.6 |

| 10. | Luteolin | 5,280,445 | C15H10O6 | −6.1 | −7.3 | −7.6 |

| 11. | Quercetin | 5,280,343 | C15H10O7 | −5.9 | −7.1 | −7.0 |

| 12. | Rutin | 5,280,805 | C27H30O16 | −6.2 (−7.2)* | −8.2 (−8.9)* | −6.8 (−7.5)* |

| 13. | Sinapic acid | 637,775 | C11H12O5 | −5.6 | −5.5 | −6.7 |

| 14. | Vanillic acid | 8468 | C8H8O4 | −5.4 | −4.8 | −5.0 |

2.2 Molecular docking studies

Molecular docking was achieved utilizing Autodock-Vina enabled PyRx (https://pyrx.sourceforge.io), where the Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm (LGA) was employed as a scoring function (Trott and Olson, 2010). The molecular docking of ligands with target proteins namely 2BEG, 2MXU, and 2NAO was performed inside a grid-box of dimensions (46 × 23 × 27), (68 × 50 × 66), and (35 × 70 × 64) Å, respectively. The most optimal configuration of each ‘protein–ligand complex’ was created and evaluated using Discovery Studio 2020 (BIOVIA) (https://discover.3ds.com/discovery-studio-visualizer-download). The ligands’ dissociation coefficient (Kd) for the target protein was determined from binding energy (ΔG) employing the following formula (Rehman et al., 2014):

2.3 Molecular dynamics simulation

The stability of the 2BEG-Diosmetin, 2MXU-Rutin, and 2NAO-Genistein complexes was evaluated using GROMACS 2022.4 (https://zenodo.org/records/6451564) for molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. Protein structures were generated with the CHARMM36 force field and TIP3P water models, and the CHARMM General Force Field (CGenFF) was used for the compounds. Simulations were carried out in a dodecahedron-shaped box with the protein–ligand complex centered and at least 1.0 nm from the edges, using TIP3P water and Na+ or Cl- ions to neutralize and mimic physiological conditions with 150 mM NaCl. Energy minimization involved up to 50,000 “steepest descent” steps. The system was equilibrated in NVT and NPT ensembles at 300 K and 1.0 bar, respectively, with temperature and pressure controlled by the Berendsen thermostat and Parrinello-Rahman barostat. A 100 ns production run was performed with a 2-fs time step using the Leapfrog integrator and LINCS for constraints, with a van der Waals cutoff of 1.2 nm. Results were analyzed and presented as means with standard deviations, based on triplicate studies.

2.4 Determination of physicochemical and ADMET properties

The physicochemical and ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) properties of the selected compounds were analyzed using the pkCSM web server, (https://biosig.lab.uq.edu.au/pkcsm/). The pkCSM tool provided predictions for key properties such as molecular weight, logP, and aqueous solubility, along with evaluations of critical pharmacokinetic parameters like gastrointestinal absorption, blood–brain barrier permeability, and hepatotoxicity (Pires et al., 2015).

3 Results and discussion

In AD, Aβ peptide variants generated from the breakdown of the Amyloid precursor protein (APP) form the core of insoluble plaques (Henning-Knechtel et al., 2020). In humans, two prominent isoforms stand out: Aβ1−40 and Aβ1−42, of which Aβ1−42 is of relevance to AD. An augmented Aβ1−42/Aβ1−40 ratio triggers the formation of Aβ amyloid fibrils, fostering neurotoxicity, and inducing tau pathology, culminating in neurodegeneration (Breijyeh and Karaman, 2020). Given the intricate interactions, Aβ1−42 serves as our selected model protein. To account for the protein's diverse conformations, we have opted to focus our investigations on three distinct conformers (PDB Ids: 2BEG, 2MXU, and 2NAO) of the same target, Aβ1−42. This inclusive approach aims to unravel the complex interplay between protein structures and the factors that contribute to AD pathology.

3.1 Molecular docking study

The validity of the docking method utilized in this investigation was established through a validation process involving the molecular docking between 2NAO and a known compound, namely CID_9998128. Our findings demonstrated that CID_9998128 occupied the identical binding site on 2NAO, consistent with earlier reports (Thai et al., 2018). The interaction of CID_9998128 with amino acid residues, including Phe4, His6, Ser8, Gly9, Tyr10, Glu11, Val12, and His13 of chains D, E, and F, was observed. The compound CID_9998128 established three conventional hydrogen bonds and seven hydrophobic interactions (such as Pi-Pi T-shaped, Pi-Pi Stacked, Alkyl, and Pi-Alkyl). Given the reproducibility of these results with the previously published report (Thai et al., 2018), it suggests that the in-silico docking principle employed in this investigation is indeed valid. The analyses of molecular docking of target proteins with natural compounds suggest that all the studied ligands were bound between different filaments of the Aβ1-42 fiber (Table 1, Figs. 1-3). The docking energy of ligands was in the range of −4.7 to −7.2 kcal/mol, −4.8 to −8.2 kcal/mol, and −5.0 to −8.0 kcal/mol for 2BEG, 2MXU, and 2NAO, respectively. In addition, docking energies of the most promising compounds namely Diosmetin, Rutin, and Genistein were calculated using the Glide SP module (Schrodinger, LLC, NY, USA), as reported earlier (AlAjmi et al., 2018). For the 2BEG target, the energies were −7.9, −7.2, and −7.6 kcal/mol for Diosmetin, Rutin, and Genistein, respectively. For the 2MXU target, the energies were −7.8, −8.9, and −8.1 kcal/mol, respectively. For the 2NAO target, the energies were −7.7, −7.5, and −7.9 kcal/mol, respectively.

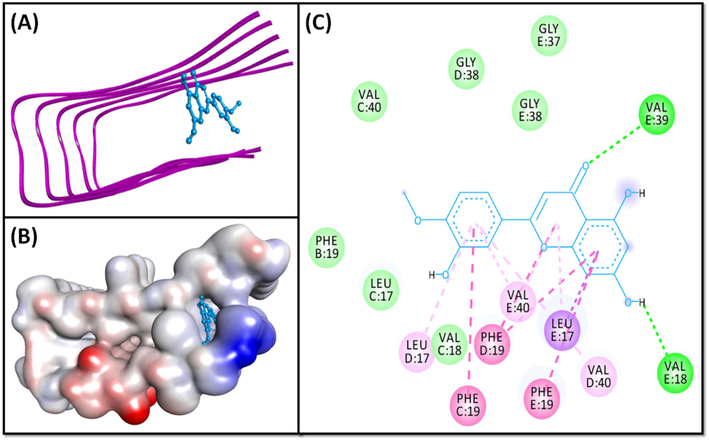

- Molecular docking of Diosmetin with 2BEG. (A) 2D docking pose, (B) 3D docking pose, and (C) Molecular interaction between 2BEG and Diosmetin.

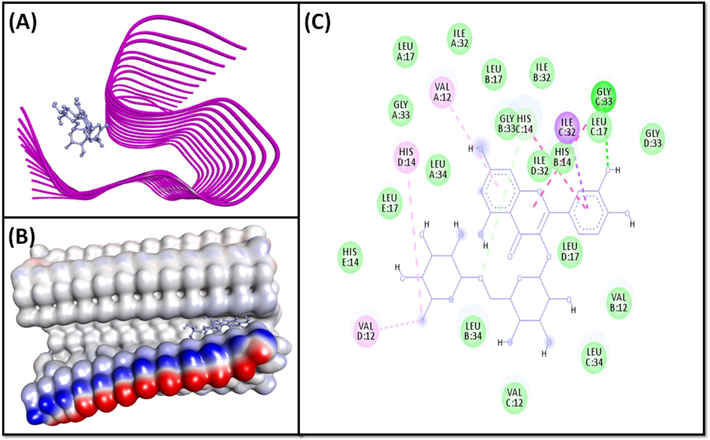

- Molecular docking of Rutin with 2MXU. (A) 2D docking pose, (B) 3D docking pose, and (C) Molecular interaction between 2MXU and Rutin.

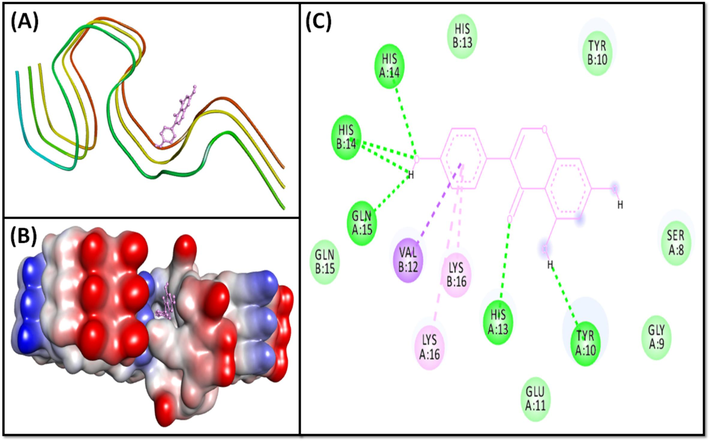

- Molecular docking of Genistein with 2NAO. (A) 2D docking pose, (B) 3D docking pose, and (C) Molecular interaction between 2NAO and Genistein.

Amongst the studied ligands, Diosmetin, Rutin, and Genistein displayed the lowest docking energy towards 2BEG, 2MXU, and 2NAO, respectively. Diosmetin, a bioactive flavonoid, has potential therapeutic applications including anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidant, anti-microbial, and analgesic effects (Garg et al., 2022). Further, Genistein, an isoflavone from legumes, exhibits anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-proliferative, and anti-microbial properties (Khan et al., 2022). Rutin, a flavonol, is known for its anti-oxidant, cytoprotective, anti-carcinogenic, neuroprotective, and cardioprotective properties (Ganeshpurkar and Saluja, 2017). Flavonoids like Genistein (AlFaris et al., 2021) and Rutin (Al Juhaimi et al., 2018) have been reported in Saudi Arabian dates, while Diosmetin derivatives have been extracted from date palms using UPLC/MS/MS techniques (Alshwyeh, 2020).

The 2BEG-Diosmetin pair was held by two standard hydrogen bonds (E:Val39:HN, and E:Val18:O), and ten hydrophobic interactions with E:Leu17:CD2 (one Pi-Sigma interaction), C:Phe19 (one Pi-Pi T-Shaped interaction), D:Phe19 (two Pi-Pi T-Shaped interactions), E:Phe19 (one Pi-Pi T-Shaped interaction), E:Leu17 (one Pi-Alkyl interaction), E:Val40 (one Pi-Alkyl interaction), D:Val17 (one Pi-Alkyl linkage), D:Val40 (one Pi-Alkyl linkage), and E:Val40 (one Pi-Alkyl interaction) (Fig. 1, Table 2). Further, Diosmetin formed several van der Waals’ interactions with B:Phe19, C:Leu17, C:Val18, C:Val40, D:Gly38, E:Gly37, and E:Gly38. The docking energy of the 2BEG:Diosmetin complex is −7.2 kcal/mol, corresponding to a binding affinity of 1.91 × 105 M−1.

| Interaction between donor and acceptor atoms | Distance (Å) | Nature of interaction | Binding energy (ΔG), kcal/M | Binding affinity (Kd), M−1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2BEG-Diosmetin | ||||

| E:VAL39:HN − LIG:O | 2.9424 | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | −7.2 | 1.91 × 105 |

| LIG:H − E:VAL18:O | 2.1186 | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | ||

| E:LEU17:CD2 − LIG | 3.2196 | Hydrophobic (Pi-Sigma) | ||

| C:PHE19 − LIG | 5.1366 | Hydrophobic (Pi-Pi T-shaped) | ||

| D:PHE19 − LIG | 4.3641 | Hydrophobic (Pi-Pi T-shaped) | ||

| D:PHE19 − LIG | 5.3534 | Hydrophobic (Pi-Pi T-shaped) | ||

| E:PHE19 − LIG | 4.5794 | Hydrophobic (Pi-Pi T-shaped) | ||

| LIG − E:LEU17 | 5.0995 | Hydrophobic (Pi-Alkyl) | ||

| LIG − E:VAL40 | 5.0625 | Hydrophobic (Pi-Alkyl) | ||

| LIG − D:LEU17 | 4.8759 | Hydrophobic (Pi-Alkyl) | ||

| LIG − D:VAL40 | 5.4053 | Hydrophobic (Pi-Alkyl) | ||

| LIG − E:VAL40 | 5.2489 | Hydrophobic (Pi-Alkyl) | ||

| 2MXU-Rutin | ||||

| C:GLY33:HN − LIG:O | 2.6673 | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | −8.2 | 1.03 × 106 |

| C:HIS14:CE1 − LIG:O | 3.5188 | Carbon Hydrogen Bond | ||

| C:ILE32:CD1 − LIG | 3.9196 | Hydrophobic (Pi-Sigma) | ||

| C:HIS14 − LIG | 4.8478 | Hydrophobic (Pi-Pi Stacked) | ||

| C:GLY33:C,O; LEU34:N − LIG | 5.605 | Hydrophobic (Amide-Pi Stacked) | ||

| LIG:C − D:VAL12 | 4.7258 | Hydrophobic (Alkyl) | ||

| D:HIS14 − LIG:C | 5.2573 | Hydrophobic (Pi-Alkyl) | ||

| LIG − A:VAL12 | 5.3754 | Hydrophobic (Pi-Alkyl) | ||

| 2NAO-Genistein | ||||

| A:HIS13:HD1 − LIG:O | 2.5571 | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | −8 | 7.37 × 105 |

| A:HIS14:HN − LIG:O | 2.9847 | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | ||

| B:HIS14:HN − LIG:O | 2.8596 | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | ||

| LIG:H − A:GLN15:O | 1.9206 | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | ||

| LIG:H − B:HIS14:O | 2.7283 | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | ||

| LIG:H − A:TYR10:O | 2.4852 | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | ||

| B:VAL12:CG2 − LIG | 3.9002 | Hydrophobic (Pi-Sigma) | ||

| LIG − A:LYS16 | 5.1099 | Hydrophobic (Pi-Alkyl) | ||

| LIG − B:LYS16 | 4.4031 | Hydrophobic (Pi-Alkyl) | ||

The 2MXU-Rutin system was stabilized by one classical hydrogen linkage with C:Gly33:HN, and one carbon-hydrogen bond with C:His14:CE1 (Fig. 2A, 2B). The complex was also stabilized by six hydrophobic linkages with C:Ile32-CD1 (one Pi-Sigma interaction), C:His14 (one Pi-Pi stacked interaction), C:Gly33:C-O; Leu34:N (one Amide-Pi interaction), D:Val12 (one Alkyl interaction), D:His14 (one Pi-Alkyl interaction), and A:Val12 (one Pi-Alkyl interaction) (Fig. 2, Table 2). The system further revealed numerous van der Waals connections , such as A:Leu17, A:Ile32, A:Gly33, A:Leu34, B:Val12, B:His14, B:Leu17, B:Ile32, B:Gly33, B:Leu34, C:Val12, C:Leu34, D:Leu17, D:Ile32, D:Gly33, E:His14, and E:Leu17. The binding free energy of the 2MXU-Rutin combination was −8.2 kcal/mol, consistent with the dissociation constant of 1.03 × 106 M−1 (Table 2). Furthermore, the 2NAO-Genistein complex was stabilized by six conventional hydrogen bonds with A:Tyr10:O, A:His13:HD1, A:His14:HN, A:Gln15:O, B:His14:HN, and B:His14:O; and three hydrophobic interactions with B:Val12:CG2 (Pi-Sigma interaction), A:Lys16, (Pi-Alkyl interactions) and B:Lys16 (Pi-Alkyl interactions) (Fig. 3, Table 2). Genistein also established several van der Waals’ connections such as A:Ser8, A:Gly9, A:Glu11, B:Tyr10, B:His13, and B:Gln15. The docking energy of the 2NAO-Genistein interaction was −8.0 kcal/mol, equivalent to a dissociation constant of 7.37 × 105 M−1 (Table 2).

3.2 Molecular dynamics simulation

3.2.1 Root mean square deviation (RMSD)

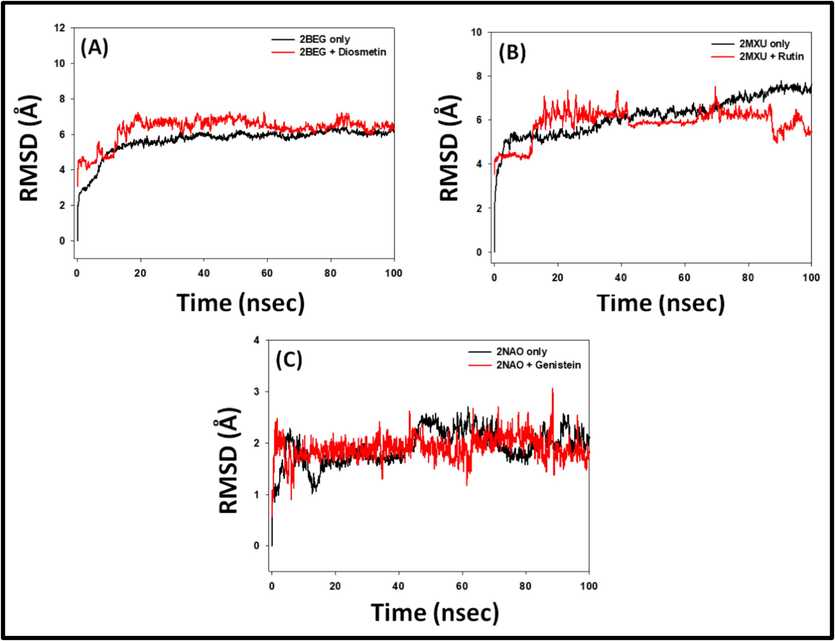

The RMSD value of a protein–ligand pair is commonly used to assess the complex's durability and dynamical character. Thus, we calculated the RMSD of targeted peptides combined with their respective ligand over a time duration of 100 ns (Fig. 4). The RMSD of 2BEG alone displayed some fluctuation during the first 0–15 ns and then achieved symmetry from 20 ns onwards. Also, the RMSD of 2BEG in conjunction with Diosmetin stayed constant during the 20–100 ns simulation time, suggesting the unchanging character of the 2BEG-Diosmetin pair. The mean RMSD values of 2BEG alone, and 2BEG-Diosmetin complex during 20–100 ns were 5.48 ± 0.32 Å, and 6.89 ± 0.48 Å respectively (Fig. 4A).

- Molecular dynamics simulation 2BEG, 2MXU, and 2NAO with their respective bioactive compounds Diosmetin, Rutin, and Genistein. (A) Root mean square deviation (RMSD) of 2BEG in the absence and presence of Diosmetin, (B) RMSD of 2MXU in the absence and presence of Rutin, and (C) RMSD of 2NAO in the absence and presence of Genistein.

Likewise, the RMSD of 2MXU alone displayed some fluctuation during 0–10 ns, afterward attaining stability. The RMSD of 2MXU in the presence of Rutin showed some variation during 0–20 ns and then continued to be steady across 20–100 ns simulation time, hinting at the complex’s stability. The mean RMSD estimates of 2MXU only, and 2MXU-Rutin conjugate during 20–100 ns were 5.97 ± 0.26 Å, and 6.07 ± 0.37 Å respectively (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, the RMSD of 2NAO alone or in the presence of Genistein was consistent during the whole MS study. The mean RMSD estimates of 2NAO only, and 2NAO-Genistein conjugate during 0–100 ns were found to be 2.14 ± 0.13 Å, and 1.88 ± 0.09 Å, respectively (Fig. 4C). During the MD simulation, the steady RMSD values indicated the formation of a strong association between the protein and its ligand. Furthermore, it revealed that there existed no significant alterations in the overall conformation of the peptide-ligand system.

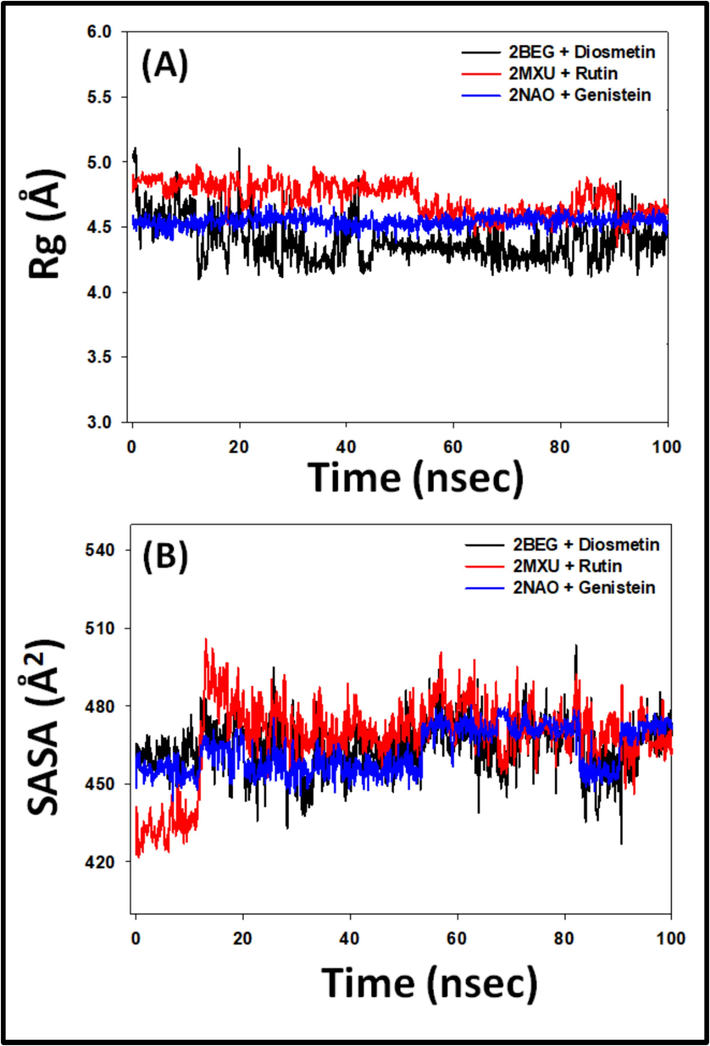

3.2.2 Radius of gyration (Rg) and solvent accessible surface area (SASA)

The Rg represents the peptide-ligand's compact dimensions, whereas the SASA evaluates the protein–ligand complex's interaction with the liquid. Each of them, consequently, offers details on the resilience of the peptide-ligand composite during the MS study. Herein, the Rg of 2BEG, 2MXU, and 2NAO was evaluated in combination with their respective ligands i.e. Diosmetin, Rutin, and Genistein respectively (Fig. 5A). The Rg of 2BEG-Diosmetin, 2MXU-Rutin, and 2NAO-Genistein conjugates varied from 4.14-5.16 Å, to 4.43–4.91 Å, and 4.52–4.64 Å respectively, with a mean value of 4.58 ± 0.34 Å, 4.86 ± 0.17 Å and 4.57 ± 0.06 Å, respectively (Fig. 5A). The SASA of 2BEG, 2MXU, and 2NAO in the company of their respective ligands i.e. Diosmetin, Rutin, and Genistein during 20–100 ns simulation fluctuated in the range of 423.4–503.7 Å2, 491.7–508.5 Å2, and 444.6–476.4 Å2 respectively, with a mean of 470.8 ± 17.3 Å2, 478.3 ± 18.1 Å2, and 467.4 ± 13.9 Å2 correspondingly (Fig. 5B). The robustness of the protein–ligand complex is confirmed by these data, which show that the differences in Rg and SASA of 2BEG, 2MXU, and 2NAO combined with their respective ligands did not diverge considerably.

- (A) Radius of gyration, and (B) Solvent accessible surface area (SASA) of 2BEG, 2MXU, and 2NAO in the absence and presence of Diosmetin, Rutin, and Genistein.

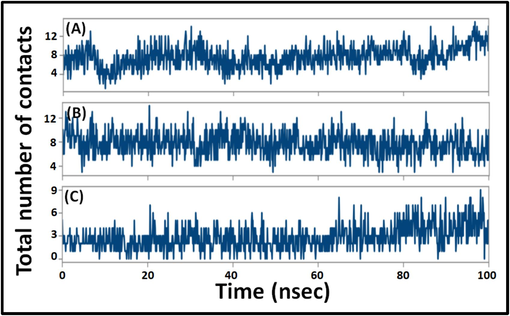

3.2.3 Total number of contacts between proteins and ligands

The overall number of permanent connections that are generated between a specific protein and its binding partner determines how strong the system is. Here, the complete set of interactions between 2BEG and Diosmetin, 2MXU and Rutin, as well as 2NAO and Genistein over simulation time was computed (Fig. 6). In 2BEG-Diosmetin system, the total number of contacts varied in the 1–15 range, with no less than 7 contacts. Likewise, the total contacts between 2MXU and Rutin varied from 3 to 14, with an average of 8 contacts. Further, the contacts between 2NAO and Genistein were in the range of 0–9, with an average of 4 interacting regions. These findings point to the establishment of a persistent ligand–protein combination.

- Variation in total number of contacts between proteins and ligands. (A) 2BEG-Diosmetin, (B) 2MXU-Rutin, and (C) 2NAO-Genistein complexes.

The Aβ peptide exits in several polymorphic forms; each characterized by a unique conformation and motif (Miller et al., 2010). Numerous pivotal conformational features of Aβ1-42 fibrils are now available. For example, Aβ1-42 fibrils can form a trifold-β pattern consisting of three separate overlapping parallel β-sheets (Xiao et al., 2015). Alternatively, they can also adopt a β-sheet–β-turn–β-sheet motif, featuring two inter-molecular, parallel, and in-register β-strands (Lührs et al., 2005). In our investigation, the model peptides 2MXU and 2NAO are S-shaped dodecamers and trimer respectively, whereas 2BEG is a U-shaped fibril. In addition, it was discovered that the residues including Val12, His13, His14, Lys16, Leu 17, Phe19, Ile32, Gly33, Leu34, and Val40 interacted actively with the ligands (Table 2), which are in concordance with previous studies (Kuang et al., 2015; Xi et al., 2016). In 2BEG protofilament, the residues Leu134, Phe19, Val36, and Ala21 of one β-sheet mediate the hydrophobic intermolecular contacts with the even-numbered residues of a parallel β-strand (Petkova et al., 2002). Residue pair Asp23-Lys28, connects these two strands via an intermolecular salt bridge, contributing to the overall stability of the “U” shape of the protofibril (Jarmuła et al., 2022). Further, a framework of inter-and intra-strand connections stabilizes this U-shaped proto-fibril. Notably, this network includes a π–π interaction involving the aromatic rings of internally present Phe19 and Phe20 located on the exterior of the peptide (Ahmed et al., 2010). In our study, Phe19 is involved in binding the ligand via π-π hydrophobic interaction, while Leu17 and Val40 form π-Alkyl bonding with the Diosmetin (Fig. 1).

The 3-D conformation of 2MXU significantly deviates from a typical β-loop-β motif generally obtained in high-resolution structures of Aβ1-40 peptides. For instance, in the 2MXU conformer, specific side chains interactions like those concerning Phe19 and Leu34 that are previously reported in solid state NMR spectra of Aβ1-42 fibrils, are lacking (Villalobos Acosta et al., 2018). Moreover, cross-peaks of several key residues including Val12, His13, and His14 are also absent from the spectra (Lührs et al., 2005). Interestingly, in this study, these residues are shown to be involved in strong binding with the ligand through H-bond (His14) or Pi-Alkyl interaction (Val12) (Fig. 2). Additionally, the 2MXU-fibril structure reveals the presence of an ionic bond between the amino moiety of Lys28 and the C terminus of Ala42 (Xiao et al., 2015); this interaction is absent in Aβ1-40 fibrils. In the secondary structure, Gly33 is present at the loop region connecting the three β-strands, one of which involves residues from Val12 to Phe20. We observed that Gly33 interacts with several atoms of Rutin via both H-bonding and amide-Pi stacked hydrophobic interactions (Fig. 2).

In the 2NAO structure, residues 1–14 are organized in a β-sheet, while residues 15–42 construct a cross–β-sheet with hidden hydrophobic side chains. For both Aβ1-42 peptide types A and B, inter-sheet salt bridges involving Lys16, Glu22, and Ala42 stabilize the structure by linking separate cross-β sheets. Additionally, Met35 of one β-sheet interacts with Leu17 or Gln15 from the second β-strand (Villalobos Acosta et al., 2018). Our research identified hydrogen bonding between the ligand and charged residues His16, His13, and Gln15, with Lys16 engaging in Pi-Alkyl interactions with Genistein (Fig. 3).

As a rule, the lower the docking energy, the better a ligand’s binding affinity. The docking scores in Table 2 reveal that the 2NAO and 2MXU peptides have high binding affinity for the ligands, while 2BEG shows the lowest binding energy. Both 2NAO and 2MXU fibrils are stabilized by strong hydrogen bonds and significant hydrophobic interactions (π-Alkyl and π-Sigma). Previous studies noted that high docking scores were due to pi-pi stacking (in His14), hydrogen bonding between the ligand’s amine and Gly33, and hydrophobic interactions with residues Val12, Leu17, Leu34, and Ile32 (Marondedze et al., 2020). In contrast, 2BEG's stability relies mainly on hydrophobic interactions, with minimal hydrogen bonding, which may account for the lower binding affinity of Diosmetin.

3.3 Prediction of Physicochemical Properties, and Drug-Likeness potential

Molecular descriptors provide critical insights into the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of compounds, key for evaluating their drug candidacy. Diosmetin, Rutin, and Genistein have molecular weights of 300.27, 610.52, and 270.24 g/mol respectively (Table 3), highlighting significant variations in size that could impact their pharmacokinetics. Their LogP values range from −1.69 to 2.58, reflecting differences in lipid solubility that might affect their absorption and membrane permeability. The compounds also differ in structural flexibility, with rotatable bonds ranging from 1 to 6, suggesting they can adopt various conformations that could influence receptor binding. Hydrogen bonding capacities vary, with Diosmetin, Rutin, and Genistein having between 3 and 10 hydrogen bond donors and 5 to 16 acceptors, affecting their potential to form bonds with other molecules. The total polar surface areas (TPSA) of these compounds range from 112.52 to 240.90 Å2, indicating differences in solubility and interactions with aqueous environments (Table 3). These diverse molecular characteristics underscore the unique biological activities and therapeutic potentials of each compound, highlighting the importance of understanding these properties in drug development.

| Property | Diosmetin | Rutin | Genistein | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physicochemical | Molecular Weight, g/mol | 300.27 | 610.52 | 270.24 |

| Partition coefficient, LogP | 2.58 | −1.69 | 2.58 | |

| Number of rotatable bonds | 2 | 6 | 1 | |

| Number of H-bond acceptors | 6 | 16 | 5 | |

| Number of H-bond donors | 3 | 10 | 3 | |

| Topological polar surface area, Å2 | 123.99 | 240.90 | 112.52 | |

| Absorption | Water solubility (mol/L) | −3.238 | −2.892 | −3.595 |

| Caco2 permeability (10−6, cm/s) | 0.326 | −0.949 | 0.900 | |

| Intestinal absorption (human), % | 79.9 | 23.4 | 93.4 | |

| Skin Permeability (log Kp) | −2.735 | −2.735 | −2.735 | |

| P-glycoprotein substrate | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| P-glycoprotein I inhibitor | No | No | No | |

| P-glycoprotein II inhibitor | No | No | No | |

| Distribution | VDss (human), log L/Kg | 0.709 | 1.663 | 0.094 |

| Fraction unbound (human), Fu | 0.068 | 0.187 | 0.087 | |

| BBB permeability, log BB | −0.954 | −1.899 | −0.710 | |

| CNS permeability, log PS | −2.316 | −5.178 | −2.048 | |

| Metabolism | CYP2D6 substrate | No | No | No |

| CYP3A4 substrate | No | No | No | |

| CYP1A2 inhibitor | Yes | No | Yes | |

| CYP2C19 inhibitor | Yes | No | Yes | |

| CYP2C9 inhibitor | Yes | No | No | |

| CYP2D6 inhibitor | No | No | No | |

| CYP3A4 inhibitor | No | No | No | |

| Excretion | Total Clearance, log ml/min/Kg | 0.598 | −0.369 | 0.151 |

| Renal OCT2 substrate | No | No | No | |

| Toxicity | AMES toxicity | No | No | No |

| Max. tolerated dose (human), log mg/Kg/day | 0.420 | 0.452 | 0.478 | |

| hERG I inhibitor | No | No | No | |

| hERG II inhibitor | No | Yes | No | |

| Hepatotoxicity | No | No | No | |

| Skin Sensitization | No | No | No | |

3.4 Analysis of ADMET properties

The ADMET analysis of Diosmetin, Rutin, and Genistein highlights their potential as therapeutic agents (Table 3). Their solubility values of −3.238, −2.892, and −3.595 mol/L suggest good bioavailability. Caco-2 permeability results show Diosmetin (0.326 × 10−6 cm/s) and Genistein (0.900 × 10−6 cm/s) have better potential for oral absorption than Rutin, which has a negative value. This is reflected in their intestinal absorption rates: Diosmetin at 79.9 %, Rutin at 23.4 %, and Genistein at 93.4 %, indicating Rutin’s lower efficiency. All three compounds have a similar skin permeability value of −2.735, suggesting comparable potential for topical use. They are substrates for P-glycoprotein but do not inhibit P-glycoprotein I or II, minimizing concerns about drug interactions.

Regarding distribution, Diosmetin (0.709 L/Kg) and Rutin (1.663 L/Kg) have higher volumes of distribution compared to Genistein (0.094 L/Kg), indicating more extensive body distribution for Rutin (Table 3). The fraction unbound (Fu) values are 0.068 for Diosmetin, 0.187 for Rutin, and 0.087 for Genistein, suggesting that Rutin has a higher proportion of unbound drug in the plasma, which could enhance its activity but also increase the risk of drug interactions. Metabolically, Diosmetin inhibits CYP1A2, CYP2C19, and CYP2C9, while Genistein inhibits CYP1A2 and CYP2C19. These interactions may affect the metabolism of other drugs, necessitating careful consideration in combination therapies. None of the compounds show AMES toxicity or hepatotoxicity. Diosmetin, Rutin, and Genistein have clearance rates of 0.598 ml/min/kg, −0.369 ml/min/kg, and 0.151 ml/min/kg, respectively. Rutin’s negative clearance rate suggests possible elimination issues, and its inhibition of hERG II channels may pose a risk of cardiotoxicity, warranting further investigation (Table 3).

Diosmetin and Genistein exhibit favorable pharmacokinetic profiles for oral use, owing to their higher permeability and absorption rates. Conversely, Rutin's lower absorption rate could limit its effectiveness. Enhancing Rutin's bioavailability and validating these results in vivo are needed. While Diosmetin, Rutin, and Genistein show promising safety profiles with no hepatotoxicity or skin sensitization, further investigation is necessary to assess metabolic interactions and Rutin's potential cardiotoxicity to ensure their clinical safety and efficacy.

3.5 Potential mechanism of action

The therapeutic action of date palm is believed to stem from its diverse botanicals with various physiological effects. Some compounds directly inhibit Aβ fibril formation. Flavonoids like resveratrol can prevent Aβ1-42 fibril formation and convert the peptide into non-toxic aggregates (Phan et al., 2019). Diosmetin reduces Aβ accumulation by protecting against Advanced Glycation End Products (AGEs)-induced reactive oxygen species (ROS), downregulating Aβ production, and promoting its degradation (Lai et al., 2022). Rutin improves cognitive function in mice by reducing tau deposits and modulating its phosphorylation (Sun et al., 2021). Genistein protects against Aβ toxicity by inhibiting protein kinase B inactivation and tau hyperphosphorylation (Petry et al., 2020). Further, Genistein also acts as a dual inhibitor of Aβ and hIAPP aggregation (Ren et al., 2018) and has shown potential in crossing the blood–brain barrier to reduce Aβ-related neurotoxicity in vivo (Duan et al., 2021). These findings suggest that date palm metabolites have potential as treatments for Alzheimer's disease, but further research is needed to clarify the specific roles and mechanisms of each flavonoid in detail.

3.6 Limitations of the study

Computational approaches offer significant potential to streamline drug development and clinical research, reducing the need for animal models and human trials while predicting toxicities more efficiently. Molecular simulations, key to these methods, can predict binding affinities and interactions with Alzheimer's-related proteins. However, molecular docking has limitations, including limited ligand and receptor conformation sampling and reliance on estimated scoring algorithms, which may not always align with experimental results. Moreover, it is important to note that the docking and simulation studies were performed in isolation, without considering the presence of other biomolecules. These studies do not mimic the cellular milieu as interactions inside the cell are different from those encountered in the lab. Therefore, in vitro as well as in vivo studies are required to validate the findings of the present study.

4 Conclusions

Given the strong link between Aβ1-42 aggregation and AD pathogenesis, our study evaluated the anti-aggregation potential of phytochemicals present in Ajwa dates. The molecular docking and dynamics simulation results validate the effectiveness of Diosmetin, Rutin, and Genistein in binding to Aβ1-42 fibrils, with low docking energies indicating strong binding affinities. Among the three, Diosmetin exhibited the most stability in complex with 2BEG, while Rutin and Genistein showed stronger interactions with 2MXU and 2NAO, respectively. The stability of these complexes was supported by consistent RMSD, Rg, and SASA values and a significant number of persistent contacts during the simulation. Additionally, the analysis of physiochemical and ADMET properties suggests these compounds have favorable drug-like characteristics, with varied pharmacokinetics and safety profiles, highlighting their potential as therapeutic agents. However, further studies are necessary to fully explore their neuroprotective potential and in vivo efficacy.

5 Data availability statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Funding

This research was funded by the Deputyship for Research & Innovation, Ministry of Education in Saudi Arabia, grant number IFP-2020–40.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Abdulaziz Bin Dukhyil: Writing – original draft, Validation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Qamar Zia: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Data curation, Conceptualization. Md Tabish Rehman: Writing – original draft, Validation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. Mohammad Z. Ahmed: Writing – original draft, Supervision, Software, Resources, Formal analysis. Saeed Banawas: Writing – original draft, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Data curation, Conceptualization. Azfar Jamal: Writing – review & editing, Software, Resources, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis. Mohammad Owais: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation. Mohammed Alsaweed: Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Methodology, Formal analysis. Yaser E. Alqurashi: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Software, Methodology, Formal analysis. Munerah Hamed: Supervision, Software, Methodology, Formal analysis. Danish Iqbal: Writing – original draft, Software, Investigation, Data curation. Mohamed El Oirdi: Writing – review & editing, Resources, Project administration, Methodology. Mohammad Aatif: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deputyship for Research & Innovation, Ministry of Education in Saudi Arabia for funding this research work (IFP-2020-40).

References

- Effects of Aβ-derived peptide fragments on fibrillogenesis of Aβ. Sci. Rep.. 2021;11:19262.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Structural conversion of neurotoxic amyloid-β1–42 oligomers to fibrils. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol.. 2010;17:561-567.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effect of date varieties on physico-chemical properties, fatty acid composition, tocopherol contents, and phenolic compounds of some date seed and oils. J. Food Process. Preserv.. 2018;42:e13584.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pharmacoinformatics approach for the identification of Polo-like kinase-1 inhibitors from natural sources as anti-cancer agents. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.. 2018;116:173-181.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antioxidant content determination in ripe date fruits (Phoenix dactylifera L.): a scoping review. Food Anal. Methods. 2021;14:897-921.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Protective effects of Ajwa date extract against tissue damage induced by acute diclofenac toxicity. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci.. 2019;14:553-559.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Phenolic profiling and antibacterial potential of Saudi Arabian native date palm (Phoenix dactylifera) cultivars. Int. J. Food Prop.. 2020;23:627-638.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Role of Ajwa date fruit pulp and seed in the management of diseases through in vitro and in silico analysis. Biology (Basel).. 2022;11:78.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Comprehensive review on Alzheimer’s disease: causes and treatment. Molecules. 2020;25:5789.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Study on the neuroprotective effects of Genistein on Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Behav.. 2021;11:e02100.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biological, nutritive, functional and healthy potential of date palm fruit (Phoenix dactylifera L.): current research and future prospects. Agronomy. 2022;12:876.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The pharmacological potential of rutin. Saudi Pharm. J.. 2017;25:149-164.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Comprehensive review on therapeutic and phytochemical exploration of diosmetin: a promising moiety. Phytomedicine plus. 2022;2:100179

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Destabilization potential of phenolics on Aβ fibrils: mechanistic insights from molecular dynamics simulation. PCCP. 2020;22:19643-19658.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Designed cell-penetrating peptide inhibitors of amyloid-beta aggregation and cytotoxicity. Cell Reports Phys. Sci.. 2020;1:100014

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Key residue for aggregation of amyloid-β peptides. ACS Chem. Nerosci.. 2022;13:3139-3151.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Consecutive aromatic residues are required for improved efficacy of β-sheet breakers. Int. J. Mol. Sci.. 2022;23:5247.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Multifaceted Pharmacological potentials of Curcumin, Genistein, and Tanshinone IIA through proteomic approaches: an in-depth review. Cancers (Basel).. 2022;15:249.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Investigation of the binding profiles of AZD2184 and Thioflavin T with amyloid-β(1–42) fibril by molecular docking and molecular dynamics methods. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2015;119:11560-11567.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The amyloid cascade hypothesis in alzheimer’s disease: should we change our thinking? Biomolecules. 2023;13:453.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Diosmetin targeted at peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma alleviates advanced Glycation end products induced neuronal injury. Nutrients. 2022;14:2248.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- 3D structure of Alzheimer’s amyloid-β(1–42) fibrils. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.. 2005;102:17342-17347.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Computational investigation of the binding characteristics of β-amyloid fibrils. Biophys. Chem.. 2020;256:106281

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Polymorphism in Alzheimer Aβ amyloid organization reflects conformational selection in a rugged energy landscape. Chem. Rev.. 2010;110:4820-4838.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The impact of natural compounds on S-shaped Aβ42 fibril: from molecular docking to biophysical characterization. Int. J. Mol. Sci.. 2020;21:2017.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A structural model for Alzheimer’s β-amyloid fibrils based on experimental constraints from solid state NMR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.. 2002;99:16742-16747.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Genistein protects against amyloid-beta-induced toxicity in SH-SY5Y cells by regulation of Akt and Tau phosphorylation. Phyther. Res.. 2020;34:796-807.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Polyphenols modulate Alzheimer’s amyloid beta aggregation in a structure-dependent manner. Nutrients. 2019;11:756.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- pkCSM: predicting small-molecule pharmacokinetic and toxicity properties using graph-based signatures. J. Med. Chem.. 2015;58:4066-4072.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Insight into the binding mechanism of Imipenem to human serum albumin by spectroscopic and computational approaches. Mol. Pharm.. 2014;11:1785-1797.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Genistein: a dual inhibitor of both amyloid β and human islet amylin peptides. ACS Chem. Nerosci.. 2018;9:1215-1224.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s disease, inflammation, and the role of antioxidants. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. Reports. 2020;4:175-183.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Rutin prevents tau pathology and neuroinflammation in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neuroinflammation. 2021;18:131.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Compound CID 9998128 is a potential multitarget drug for Alzheimer’s disease. ACS Chem. Nerosci.. 2018;9:2588-2598.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem.. 2010;31:455.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Recent advances by In Silico and in vitro studies of amyloid-β 1–42 fibril depicted a S-shape conformation. Int. J. Mol. Sci.. 2018;19:2415.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Stability of a recently found triple-β-stranded Aβ1–42 fibril motif. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2016;120:4548-4557.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Aβ(1–42) fibril structure illuminates self-recognition and replication of amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol.. 2015;22:499-505.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effect of date palm (Phoenix dactylifera) phytochemicals on Aβ1−40 amyloid formation: an in-Silico analysis. Front. Neurosci.. 2022;16:915122

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Appendix A

Supplementary material

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2024.103424.

Appendix A

Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article: