Translate this page into:

Anaerobic co-digestion of cow manure and microalgae to increase biogas production: A sustainable bioenergy source

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Abstract

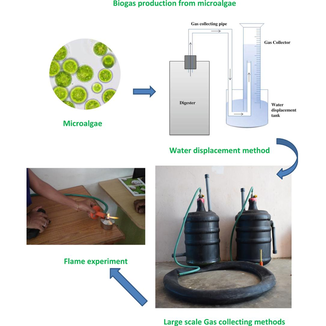

The biogas production from microalgae has gained attention due to fast depleting of fossil fuels and oil reserves. This study evaluated the anaerobic co-digestion of microalgae in various concentrations with cow manure to enhance biogas production. The biogas production of each experiment was measured using the water displacement method. The results indicated that the addition of microalgae significantly enhanced biogas production. Particularly, high methane yield of Anabaena sp. 50 %, Chlorella sp. 50 %, control was 345 ± 2.88 mL CH4/g VS, 297.96 ± 0.49 mL CH4/g VS, 138.32 ± 0.50 CH4/g VS respectively. The slurry produced by 50 % Anabaena sp. biogas plant exhibited the greatest level of seed germination. The current study demonstrated that Sorgham bicolor had the highest seed germination rate (94.2 %) root and shoot length of all crops. Therefore, it is possible to employ Anabaena sp. (50 %) and Chlorella sp. (50 %) in the rapid production of biogas. Moreover, agricultural output would be increased by using biogas slurry.

Keywords

Microalgae

Biogas production

Anaerobic co–digestion

Seed germination

1 Introduction

The ecologically friendly and highly efficient Anaerobic Digestion (AD) technology has garnered considerable attention. Furthermore, it possesses the capability to convert organic waste into biogas, primarily composed of carbon monoxide and hydrogen peroxide, along with digestate, a byproduct produced by diverse bacteria during the anaerobic digestion procedure (Li et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2023). Biogas, an environmentally friendly and sustainable energy source, has the capacity to substitute conventional fossil fuels in the production of heat and electricity. Moreover, the digestate can be utilized for the manufacturing of compound fertilizer (Xu et al., 2020). Incorporating accelerants into the anaerobic digestion (AD) system offers significant benefits and is a very efficient method for enhancing biogas output and digestate use (Wang et al., 2019). The simplicity, safety, and environmental friendliness of anaerobic digestion (AD) have generated no significant interest (Li et al., 2021). Anaerobic digestion (AD) can be classified into four separate stages: hydrolysis, acidogenesis, acetogenesis, and methanogenesis (Yun et al., 2023). The many stages are intricately linked to each other. The performance of anaerobic digestion (AD) is affected by several factors, including substrate characteristics, temperature, buffering capacity, and microbial activity. At each level, these components must satisfy exact criteria and uphold a consistent state. Inadequate modifications can result in a dearth of advancement, incongruity, and the deterioration of the anaerobic digestion process, which can affect the generation of biogas, the efficacy of substrate decomposition, and the utilization of digestate (Wang et al., 2021). Accelerants are commonly employed in AD systems due to their notable accessibility, efficiency, and immediacy, which are significant aspects that contribute to their success in facilitating development. An important area of research is analyzing the improved efficiency of anaerobic digestion (AD) systems with external catalysts by evaluating biogas production, process stability, and the degree of organic matter decomposition. Biogas generation is a dependable indicator of the energy generated by an anaerobic digestion (AD) system (Han et al., 2019). Previous studies have quantified biogas production using several metrics, including milliliters (mL), milliliters per gram of total solids (TS), milliliters per gram of volatile solids (VS), and milliliters per gram of chemical oxygen demand (COD) (Wang et al., 2022). The stability of anaerobic digestion (AD) systems is evaluated and monitored by quantifying various indicators including pH, total alkalinity (TA), volatile fatty acids (VFAs), total ammonia nitrogen (TAN), and the ratio of volatile fatty acids to total alkalinity (VFA/TA) (Gao et al., 2024). The primary objective of these indicators is to ascertain the buffer capacity and acid production that occur during the process of digestion. In addition, the evaluation of the decomposition of organic matter in the anaerobic digestion (AD) process is carried out by measuring biochemical oxygen demand (BOD), chemical oxygen demand (COD), total solids (TS), and volatile solids (VS) before and after the digestion process (Wang et al., 2022).The assessment of the AD process has been conducted utilizing these metrics; yet, there are no established indicators or pertinent thresholds.

In recent decades, there has been a significant proliferation of cow farms due to the global rise in human populations. An estimated global cattle population of 1.5 billion has been recognized (FAOSTAT, 2020). Based on statistics, these cattle farms have the capacity to discharge around 40 million metric tons of waste, with a significant portion of it consisting of manure (Baek et al., 2020). Further, multiple countries in Asia and Europe provide substantial contributions to the generation of cattle-related waste materials because of their farming practices. An example of this would be the fact that European countries have generated over 1.4 billion tonnes of organic waste products (includes manure) associated with livestock (Hangri et al., 2024). A substantial number of cattle farms have been noticed in Saudi Arabia, leading to the annual release of around 335,000 tonnes of cattle manure (Mohammed-Nour et al., 2021). In general, cattle manure has a substantial concentration of a wide range of minerals, carbon, nitrogen, heavy metals, and several kinds of microbial communities. The disposal of livestock waste in open agricultural regions has significant adverse effects on the ecosystem (Jomnonkhaow et al., 2021). A vast majority of countries have been employing cattle manure as a bio-fertilizer that has proven to be the most effective in increasing crop yield. But, improperly applying cattle manure to agricultural soil can cause significant environmental contamination. This is because it leads to the rapidly accumulation of excessive nutritive elements and other heavy metals, which in turn reduces the fertility of the soil (Atienza-Martínez et al., 2020). Since digestates from anaerobic digestion (AD) operations can be utilized as nutrient-rich soil amendments and fertilizers, they can reduce reliance on chemical fertilizers while simultaneously enhancing soil health and crop yields (Wang et al., 2019). This makes the use of digestates from AD processes economically feasible. Additionally, digestates can aid in biogas plant energy recovery, boosting overall energy production. Owners of biogas plants stand to gain more income from the prospective market for selling processed digestates as commercial goods (Zhang et al., 2018). Potential carbon credits and incentives can increase the economic benefits of reduced greenhouse gas emissions and rubbish disposal. In general, the extensive use of digestates in waste treatment encourages sustainability on both an environmental and economic level (Xu et al., 2020).

Therefore, the implementation of mitigation strategies is necessary in order to prevent the pollution that is associated with cattle manure. The production of biogas from manure through an anaerobic digestion (AD) process is one of the most effective strategies for reducing the contamination that is caused by manure. AD treatment is a tremendously effective technique for transforming a wide range of organic waste materials into valuable energy (Kavitha et al. 2015; Wang et al., 2022). For example, cattle manure contains a substantial concentration of carbohydrates (Gao et al., 2024), protein, and lipids (McInerney 1998), which renders it a superior substrate for biogas (bio-methane) production.

Microalgae has garnered significant interest from environmental professionals in recent decades due to their exceptional capabilities. Microalgae are primarily employed as promising source material for the production of biogas and other biological commodities (Erkelens et al., 2014; Ward et al., 2014; Salman et al., 2023). The incorporation of microalgae into cattle manure contained an AD system, which resulted in an increase in the production of biogas. The complex cell structure of microalgae leads to a decline in the biological decomposition during AD (Passos and Ferrer, 2014). In order to achieve efficient production of biogas, it is necessary to implement a pretreatment process when incorporating microalgae into AD (Vargas-Estrada et al., 2022).

Utilizing a particular strain of microalgae that has not been thoroughly researched in conjunction with cattle dung, our manuscript is unusual because it takes an innovative approach to anaerobic co-digestion. This technique is what makes our manuscript so unique. This research fills in a number of critical knowledge gaps that have been identified in the realm of biogas generation. In the first place, we investigate the one-of-a-kind characteristics and prospective potential of a specific strain of microalgae that has not been extensively documented. This strain has the potential to deliver improved biogas production efficiency and stability. In the second part of our research, we investigate a wide range of substrate ratios, retention periods, and operational settings to fully optimize co-digestion parameters. In addition to contributing useful data, this precise optimization also contributes to developing more efficient and effective biogas production techniques.

In addition, we present a comparison analysis between the anaerobic co-digestion of microalgae and cattle manure and with other traditional substrates. This research highlights the benefits of employing these particular substrates as well as the potential constraints that may be associated with their utilization. Regarding the selection of substrates for biogas production, this comparative approach provides a more comprehensive perspective. In addition, our manuscript contains a comprehensive environmental and economic analysis, which takes into account the environmental advantages, such as decreased emissions of greenhouse gases and recycling of nutrients, as well as an economic analysis of the cost-effectiveness and potential market implications of employing microalgae and cattle manure for the production of biogas.

An innovative co-digestion technique that incorporates advanced pretreatment procedures and the utilization of a one-of-a-kind microalgae strain, extensive parameter optimization, holistic impact evaluation, and an emphasis on practical scalability are the distinguishing characteristics of our research effort. The combination of these components helps close large knowledge gaps and contributes to developing more environmentally responsible methods of producing biogas.

The production of biogas from organic waste can be accomplished by employing the process of AD, which is one of the most effective approaches. Many different microbial communities play a significant role in the process of anaerobic digestion (Ravindran et al., 2021). It is interesting to note that AD can be separated into three separate stages: the initial stage is the hydrolysis process, the second phase is acidogenesis, and the third step is the final methanogenesis. During the initial stages, complex biological macromolecules are broken down into smaller micromolecules. subsequently, stabilize the different large chemical molecules into the essential components. In the methanogenesis process, the materials from the second phase are converted into methane (Gomez Camacho et al., 2019). In fact, several countries in Asia and Europe have successfully implemented large-scale AD methods. In China, AD plants involve the utilization of 100,000 t of sewage and 80,000 t of chicken manure to produce a substantial amount of biogas, which in turn generates 14 million KWh of electricity yearly (Chen et al., 2017). In addition, Saudi Arabia contributes significantly to the production of biogas from organic waste materials; this endeavor has increased the country annual revenue by approximately $1.25 billion US dollars (Baig et al., 2019).

This study aims to explore the possibility of using microalgae and cow dung anaerobic co-digestion as a way to increase biogas generation. The goal of the study is to increase the yield and efficiency of biogas by combining these two substrates and taking use of their complementing qualities, providing a renewable and sustainable source of bioenergy. The ultimate goals of the project are to contribute to both ecological integrity and energy independence by demonstrating the feasibility of this strategy for large-scale bioenergy production, optimizing the co-digestion procedure, and assessing the complementary impacts of the substrates.

Previous significant reports have shown that different microalgae species have been employed effectively for biogas production. On the other hand, the production of biogas through anaerobic digestion using a variety of microalgae species and cattle dung is not adequately explored. This study evaluates the hypothesis that anaerobic digestion of a combination of various microalgae species and cattle manure can increase biogas production. The main objectives of the present study are: (i) to collect the different Red Sea microalgae species in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia; (ii) to estimate biogas generation using various combinations of cow dung and microalgae.; (iii) to analyze several chemical parameters from the biogas slurry; and (iv) to assess the quality of the biogas slurry employing seed germination assay with agriculturally valuable seeds.

2 Material and methods

2.1 Collection of substrates

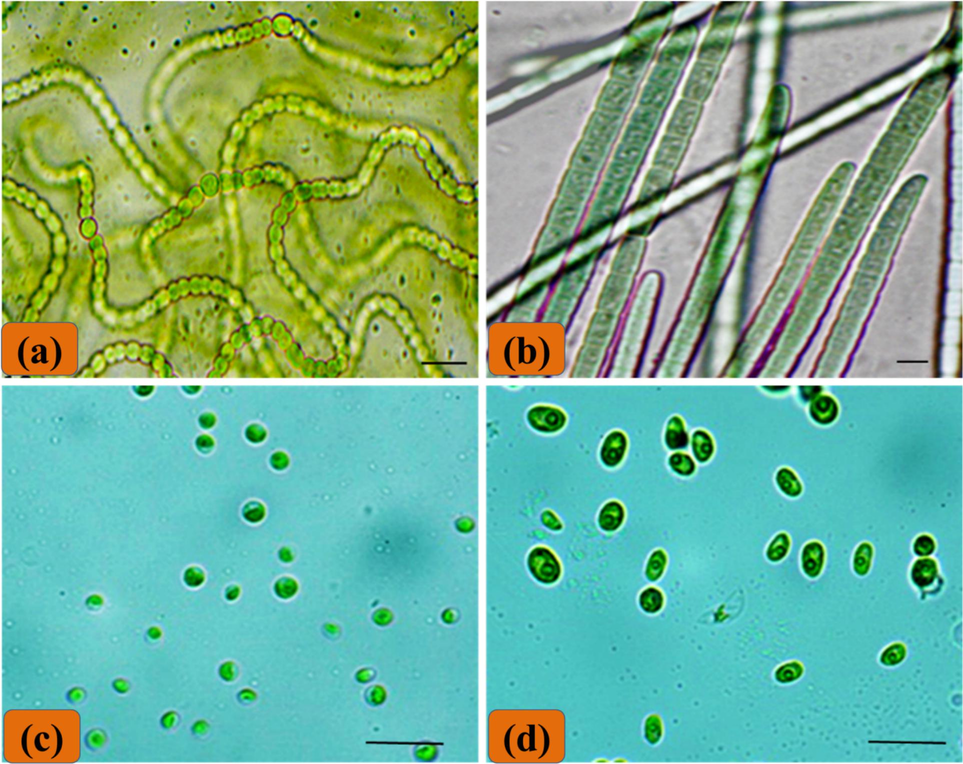

Identification of microalgae necessitates a comprehensive procedure involving several approaches. First, samples were collected and examined under a microscope to document morphological features. These samples are then grown to create pure isolates. The identification of microalgae species has been conducted following the recommended procedures by Bouck (1965), Levring (1946) and Coppejans et al. (2009). The microalgae were cultured employing BG 11 media supplemented with vitamin B12 and maintained at a temperature of 25 °C under a light intensity of 45 µmol/m-2(−|−)S-1 lx for an average of 20 days in order to reach the mid-log phase of growth. By employing FT-IR spectroscopy to examine the microalgae's biochemical composition, complementary data is acquired. The amalgamation of morphological ones such, molecular, and biochemical data ensures accurate and reliable identification, which is necessary for the microalgae species to be utilized successfully in biotechnological processes.

The cow manure was conveyed to the lab after being retrieved from the Ismail cow farm in Dammam City (26.4207° N, 50.0888° E), Saudi Arabia. The tiny plant-based waste materials in the cattle manure have been carefully separated. Then, the collected cattle manure was diluted with de-chlorinated water in equal proportions (1:1), carefully stirred for ten min at 2000 rpm, and subsequently strained through a finer nylon mesh as recommended by Khayum et al. (2018).

The four distinct microalgae species, specifically Anabaena sp., Oscillatoria sp., Chlorella sp., and Tetraselmis sp., were obtained from the Red Sea in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, at coordinates 21.5292° N and 39.1611° E (Fig. 1). The microalgae species were properly stored in uncontaminated zip-lock plastic bags under controlled cooling conditions and subsequently transported to our laboratory. Next, the microalgae species underwent a thorough washing process using mother seawater to eliminate any extra sand and other components.

External morphology of different microalgae. (a) Anabaena sp., (b) Oscillatoria sp., (c) Chlorella sp., and (d) Tetraselmis sp. Scale bar: 10 µm.

2.2 Pre-treatment process for microalgae species

Prior to the integration of microalgae into efficient biogas generation. Pretreatment methods are necessary to achieve high yields of biogas due to the intricate cell structure of microalgae. In the present study, four different species of microalgae were effectively pretreated using a combination of treatment methods, including ultra-sonication (Brand: VEVOR) with water. Sonication was performed using 10–15 % of the microalgae biomass. Additionally, the microalgae were pretreated employing hot water treatment at 120 °C, in accordance with the method (simple modification) outlined by Saleem et al. (2020).

2.3 Experimental setup

The present research was carried out in our laboratory using pilot-scale anaerobic digesters. Mainly, plastic container with a total volume of approximately 20 L was used to assemble the anaerobic digesters (Fig. 2a). The oxygen molecules have been carefully eliminated from the digester and sealed with butyl rubber caps. Further, it is closed with M−seal to ensure anaerobic conditions. Three distinct concentrations (25, 50, and 75 % v/v) have been employed to produce biogas. The production of biogas was measured daily employing the water displacement method. The entire experimental process was carried out in a mesophilic environment at a temperature of 36.85 °C. The experimental containers were shaken for 1–2 min twice daily before biogas levels were recorded (Fig. 2b) as recommended by Zhai et al. (2015).

(a) Anaerobic laboratory digesters; (b) Gas collecting methods (c) Flame experiment.

2.4 Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) analysis

In general, FT-IR (Perkin Elmer, USA) is capable of precisely identifying the numerous chemical functional groups in substrate materials. The FT-IR spectra were observed range of 4000 – 450 cm−1.

2.5 Analytical methods

The pH of the substrate materials (1:10 w/v) was measured using a digital pH meter (model − STARA1117). The estimation of total solids (TS) and total dissolved solids (TDS) was conducted following the APHA (2017) guidelines. To determine the TS, samples were collected from experimental glass bottles and subjected to an evaporation procedure utilizing a drying oven. The dried vaporized sample was exposed to a temperature of 105 °C for 1 h, after that it was allowed to cool and subsequently weighed. Where: A=amount of evaporated residue + dish, mg

B=mass of the dish, mg.

For the analysis of the TDS, samples were meticulously collected from all experimental glass bottles and subsequently cleaned to eliminate any remaining residues. A clean dish (180 ± 2 °C for 1 h in an oven) was utilized. The components that had been filtered were then transferred into the evaporating dish (clean dish), and the evaporation process was then carried out in an oven. To determine the final total dissolved solids, it is necessary to place the sample in an oven at a temperature of 180 ± 2 °C for 1 h. Where: A=amount of evaporated residue + dish, mg

B=mass of the dish, mg.

To assess the amount of nitrate, approximately 50 mL of the sample was filtered, and then 1 mL of hydrochloric acid was added, and the mixture was properly mixed. Then, A standard curve was prepared by utilizing the nitrate solution, ranging from 0 to 35.0 mL. The final samples were analyzed at a wavelength of 220 nm employing spectrophotometry to measure the nitrate concentration (Armstrong 1963). The concentration of ammonia was analyzed using the titrimetric method with the use of a boric acid solution as indicated by Meeker and Wagner (1933).

2.6 Flame test

The flame test is an essential component in the analysis of the biogas produced by the experimental digester (Fig. 2c). This evaluation was conducted carefully in a darkened room. The Bunsen burner was linked to one end of the small plastic pipe, and the bio-digester was connected to the other end of the pipe to complete the connection. Further, the quantity of biogas was determined using the flammable nature.

2.7 Seed germination assay using digested slurry

The determination of phytotoxicity activity requires assessing the quality of the final biogas slurry. We obtained four distinct seed varieties, namely Sorgham bicolor, Paspalum scrobiculatum, Oryza sativa, Zea mays, and Vigna unguiculata, from Local Market. Then, the seeds were subjected to a cleaning process using a 2 % solution of sodium hypochlorite (NaClO) for 10 min, followed by rinsing with distilled water. In order to conduct an experiment, the biogas slurry was obtained from biogas treatments and subsequently combined with distilled water in a ratio of 10:1 (v/w) as recommended by Tiquia et al. (1996). About 10 sterilized seeds of each variety were inserted on glass Petri plates containing Whatman number 1 filter paper. Biogas slurry extraction (5 mL) was added to the Petri plates, while distilled water was used as a control. The Petri plates were incubated under a tightly controlled 16-hour dark cycle for a period of 8 to 10 days. The morphometric characteristics of seeds, including germination %, shoot length, root length, fresh weight, dry weight, and number of leaves were quantified.

2.8 Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS software (version 21). The mean ± standard error was used to represent the combined seed germination and chemical characteristics. In addition, One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to assess the differences between the experimental treatments and the control group. HSD multiple comparison tests were performed at a significance level of P<0.05.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Impact of microalgae on biogas production

There has been a significant increase in the utilization of several types of microalgae in recent years for the production of biogas. In the present study, the production of biogas daily through the use of an anaerobic digester that consists of four species of microalgae (Chlorella sp., Oscillatoria sp., Tetracelmis sp., Anabaena sp.), depicted in Fig. 1, coupled with sewage water and cattle manure. Over the course of six days, experiments were conducted with varying proportions of 25 %, 50 %, and 75 %.

The combination of microalgae and cattle manure can produce a considerable amount of biogas, mainly methane. For example, the Anabaena sp. biomass at a proportion of 50 % yielded a substantial amount of methane, with a recorded value of 345 ± 2.88 mL CH4/g VS. This was followed by Chlorella at 50 % proportion, which yielded 297.96 ± 0.49 mL CH4/g VS. Then, Oscillatoria sp. at 75 % proportion, which yielded 185.0 ± 0.288 CH4/g VS. Tetracelmis sp. at 75 % ratio yielded 100.0 ± 0.577 mL CH4/g VS and the 75 % proportion of control was produced 138.32 ± 0.50CH4/g VS of methane as presented in Table 1. For biogas generation, there was a statistically (one-way ANOVA) significant difference among the various proportions. The incorporation of microalgae biomass into the anaerobic digester resulted in a substantial increase in the production of biogas. Varol and Ugurlu (2016) demonstrated that the utilization of Spirulina platensis, combined with sewage sludge under two-phase digesting conditions led to a considerable increase in methane yield 640 mL/gVS. The microalgae have a substantial number of polysaccharides, a variety of proteins, lipids, and a minimal amount of lignin, all of which contribute to an increase in the production of methane in anaerobic conditions (Perazzoli et al., 2017; Dębowski et al., 2017). In the present study, the insertion of a co-substrate of Anabaena biomass resulted in a twofold increase in the amount of methane. This may be due to the greater digestibility of Anabaena biomass in comparison to other species of microalgae. The generation of efficient biogas depends on the type of microalgae species employed (Mussgnug et al., 2010a,b). The authors recommend that Anabaena sp. is more efficient than other microalgae species such as Oscillatoria sp., Chlorella sp., and Tetraselmis sp. for biogas production. Further, the C/N ratio of the co-substrate materials plays a crucial role in regulating the production of biogas. When the C/N ratio is at an extreme level, it can potentially affect the biochemical pathways. However, previous reports could not accurately provide the optimal level of C/N ratio (Dębowski et al., 2020). In a study conducted by Deublein and Steinhauser (2008), it was found that maintaining a C/N ratio of 16 to 25 can lead to improved biogas production. This study detected a slight reduction in methane production, which may be due to insufficient water in biogas-producing systems. Anaerobic digestion of microalgae (Scenedesmus sp., Nannochloropsis sp., and Chlorella sp.), poultry manure, and sewage sludge results in a significant reduction in the production of biogas when the water content is reduced as revealed by Torres et al. (2023). The authors assert that the production of biogas is contingent upon the specific kind of substrate materials utilized in the anaerobic digestion system. The employment of inappropriate combinations of substrates can diminish the production of biogas.

Microalgae

25 %

50 %

75 %

Anabaena sp.

126 ± 0.577

345 ± 2.88

82.73 ± 0.21

Oscillatoria sp.

88.06 ± 0.26

126.0 ± 0.577

185.0 ± 0.288

Chlorella sp.

266.0 ± 0.115

297.96 ± 0.49

55.0 ± 0.115

Tetraselmis sp.

16.91 ± 0.25

42.20 ± 0.37

100.0 ± 0.577

Control

(Cattle manure)51.54 ± 0.79

87.40 ± 0.21

138.32 ± 0.50

According to the experiment, the burning test of biogas showed that a burnable gas was detected on the 10th day of fermentation in Chlorella sp., specifically in the 25 % digesters treatments. The biogas production commenced on the 10th day following the initiation of the digester. On the 16th day, the biogas ignited for the first time, producing a steady blue flame that burned for approximately 10 s (Fig. 4c). This study examined the continuous anaerobic co-digestion of a mixture of microalgae, cow dung, and sewage water. The co-digestion of microalgae with cow dung shown synergistic effects, resulting in a threefold increase in biogas production compared to the mono-digestion of cow dung.

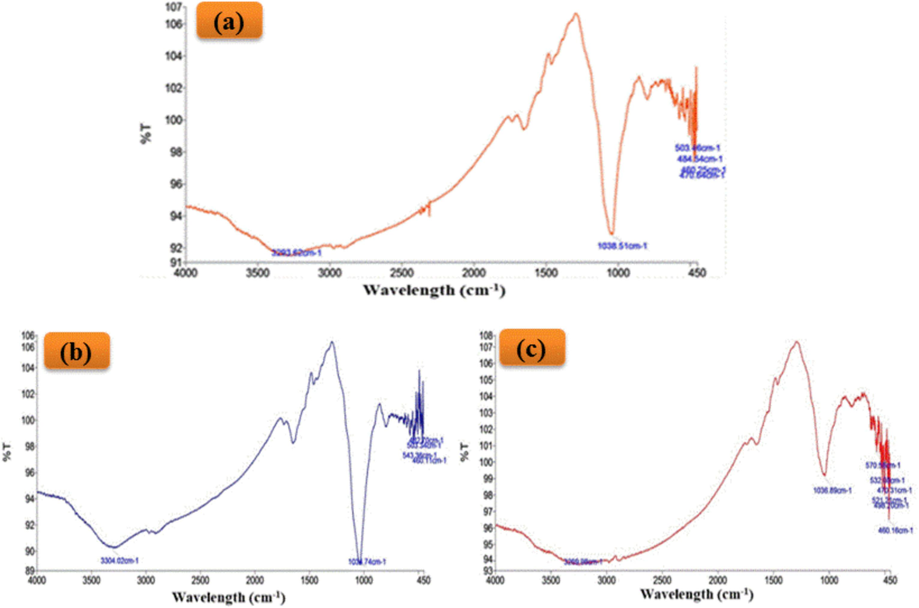

3.2 Analysis of chemical parameters and FT-IR

For determining the quality of the final substrate, it is essential to measure a wide range of chemical properties (total solids, total dissolved solids, nitrate, and ammonia) in sediment produced by biogas treatments. According to the findings of the current study, a significant concentrations of total solids, total dissolved solids, nitrate, and ammonia were found in Anabaena sp., (75 %) and Chlorella sp. (75 %). The high concentration of TS could potentially impact the production of biogas. In a study conducted by Deepanraj et al. (2014), it was found that a TS level of 7.5 % is ideal for maximizing biogas production. A recent study by Torres et al. (2023) has confirmed that a decrease of less than 8.49 % in TS levels can lead to an increase in biogas production.

In this study, the digester sludge was analyzed using FT-IR (Fig. 3). After 25 % digestion with Chlorella sp., the FT-IR spectra revealed peaks at 1645 and 1530 cm−1, indicating vibrations of C=O and N–H bonds of amide, which are related with proteins. The peaks at 3304 cm−1 revealed the presence of C–H bonds associated with polysaccharides and carbohydrates. Khayum et al. (2018) performed a similar FT-IR investigation. Hence, these peaks decrease in the after-digestion suggesting the decomposition of carbohydrates and proteins (Ben Yahmed et al., 2017).

(a) Over all experimental set up of water displacement system (a) FT-IR analysis of cow manure sludge (control) from anaerobic digestion (b) Chlorella sp., 50 % (c) Anabaena sp.,50 %.

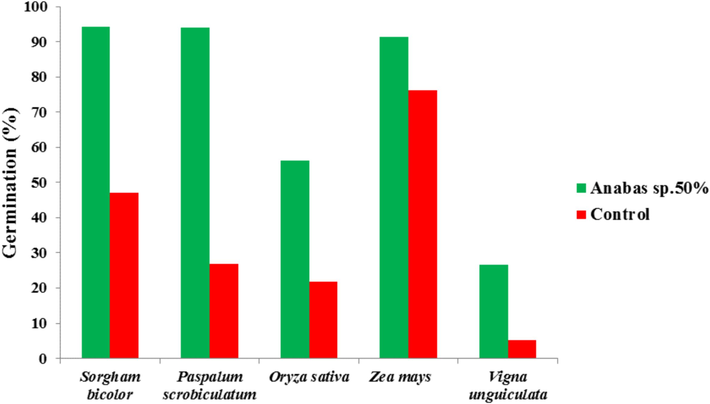

Seed germination percentages for various agriculturally valuable seeds.

3.3 Germination studies

In order to carry out the seed germination test, it is necessary to investigate the quality of the final biogas slurry. The seed germination assay was conducted using biogas slurry consisting of Anabaena sp. 50 % and a control group. The slurry from microalgae biogas plants shows the highest amount of seed germination when compared to the control (cow manure). The current study found that Sorgham bicolor had the maximum seed germination rate (94.2 %) when subjected to microalgae-associated biogas slurry (Fig. 4). In contrast, the lowest seed germination rate (5.2 %) was observed in the control group of Vigna unguiculata as presented in Fig. Microalgae biogas treatments were significantly (P<0.05) different from control biogas treatments. The seed germination can be significantly improved by using the biogas slurry, which contains several essential enzymes and chemical factors. According to Zhao et al. (2014), 75 percent biogas leachate is capable of promoting the germination of Vicia faba L. seeds. The study conducted by Miyuki et al. (2006) suggested that increasing the germination index by around 50 % is a significant indication of the absence of harmful substances in the substrate materials.

The root length of all the crop seedlings ranged from 0.3 ± 0.78 to 15.5 ± 0.02 cm per seedling. The Sorghum bicolor seeds exhibited the greatest root length, measuring 15.0 ± 0.02 cm per planting. The shoot length of all the crop planting ranged from 0.4 ± 0.0 to 12.5 ± 0.33 cm per seeding. The shoot length of Paspalum scrobiculatum reached a maximum value of 12.5 ± 0.33 cm per seedling, which was higher than the shoot length of the control seedlings (Table 2). The sludge from the Anabaena sp.50 % digester may contain numerous substances that promote plant growth, hence enhancing germination and crop development. Moreover, the authors strongly assert that microalgae-based biogas slurry exhibits a significant concentration of nitrogen and phosphorus, which effectively promotes plant growth. A study conducted by Zheng et al. (2016) found that the application of biogas slurry in the field has the potential to enhance the seedling and production of peanuts. Yu et al. (2010) demonstrated that biogas slurry contains plant vital nutritional elements such as N, P, and K, which actively improve the quality of tomatoes. In light of this, Anabaena sp. (50 %) and Chlorella sp. (50 %) have the potential to be utilized in the rapid production of biogas. Furthermore, the utilization of biogas slurry would enhance crop yield.

Biogas slurry

Sorgham bicolor

Paspalum scrobiculatum

Oryza sativa

Zea mays

Vigna unguiculata

Root length

Shoot length

Root length

Shoot length

Root length

Shoot length

Root length

Shoot length

Root length

Shoot length

Anabaena sp. (50 %)

15.0 ±

0.015.0±

0.1714.5±

0.2612.5±

0.035.1±

0.031.5±

0.0213.1±

0.062.3±

0.020.3±

0.120.40±

0.01

Control

11.0±

0.060.0±

0.06.0±

0.289.0±

0.013.71±

0.023.2±

0.0212.1±

0.062.0±

0.121.0±

0.120.2±

0.03

4 Conclusion

The study emphasizes the capacity of microalgal biomass, specifically Anabaena sp. and Chlorella sp., to augment biogas production by co-digestion with cow manure. The results demonstrate a notable enhancement in biogas production, particularly in the early stages of fermentation, when using a 50 % concentration of microalgae. Furthermore, the utilization of microalgal biomass produces a nutrient-dense slurry that is advantageous for organic farming. This study provides a valuable contribution to the progress of generating renewable energy and promoting environmental sustainability. Optimizing these processes in the future could be pivotal in shifting towards a sustainable economy by decreasing dependence on fossil fuels, minimizing emissions of greenhouse gases, and fostering circular bio economies.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Reem M. Alharbi: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation.

Declaration of competing interest

The author declares that she has no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Determination of nitrate in water by ultraviolet spectrophotometry. Anal. Chem.. 1963;35:1292.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pyrolysis of dairy cattle manure: evolution of char characteristics. J. Anal.Appl Pyrol 2020:145.

- [Google Scholar]

- Treatment of cattle manure by anaerobic co-digestion with food waste and pig manure: methane yield and synergistic effect. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2020;17(13):1-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- Enhancement of biogas production from Ulva sp. by using solid-state fermentation as biological pretreatment. Algal Res. Elsevier. 2017;27:206-214.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fine structure and organelle associations in brown algae. J. Cell Biol.. 1965;26:513-537.

- [Google Scholar]

- A sustainable biogas model in China: The case study of Beijing Deqingyuan biogas project. Sustain. Energy Rev Renew.. 2017;78:773-779.

- [Google Scholar]

- Srilanka Seaweeds Methodologies and Field Guide to the Dominant Species. University of Ruhuna, Dept. of Botany, Matora, Srilanka; 2009. p. :1-265.

- The Influence of Anaerobic Digestion Effluents (ADEs) Used as the Nutrient Sources for Chlorella sp. Cultivation on Fermentative Biogas Production. Waste and Biomass Valorization.. 2017;8:1153-1161.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effects of Microalgae Biomass Co-Substrate on Biogas Production from the Common Agricultural Biogas Plants Feedstock. Energies. 2020;13:2186.

- [Google Scholar]

- B. Deepanraj, V. Sivasubramanian, S. Jayaraj, 2014. Solid concentration influence on biogas yield from food waste in an anaerobic batch digester, International Conference and Utility Exhibition 2014 on Green Energy for Sustainable Development (ICUE 2014). https://doi.org/10.13140/2.1.2309.4405.

- Biogas from Waste and Renewable Resources. Weinheim, Germany: WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA; 2008.

- Microalgae digestate effluent as a growth medium for Tetraselmis sp. in the production of biofuels. Bioresour Technol. 2014;167:81-86.

- [Google Scholar]

- FAOSTAT, 2020. Food and agriculture data. Retrieved on 15 October 2020 from http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#home.

- Understanding of the potential role of carbon dots in promoting interspecies electron transfer process in anaerobic co-digestion under magnetic field: Focusing on methane and hydrogen production. Chem. Eng. J.. 2024;489:151381

- [Google Scholar]

- Continuous two-step anaerobic digestion (TSAD) of organic market waste: rationalising process parameters. Int. J. Energy Environ. Eng.. 2019;10:413-427.

- [Google Scholar]

- Steel slag as accelerant in anaerobic digestion for nonhazardous treatment and digestate fertilizer utilization. Bioresource Technology. 2019;282:331-338.

- [Google Scholar]

- Combining pretreatments and co-fermentation as successful approach to improve biohydrogen production from dairy cow manure. Environ. Res.. 2024;1(246):118118

- [Google Scholar]

- Membrane bioreactor-assisted volatile fatty acids production and in situ recovery from cow manure. Bioresour Technol.. 2021 Feb;321:124456

- [Google Scholar]

- Accelerating the sludge disintegration potential of a novel bacterial strain Planococcus jake 01 by CaCl2 induced deflocculation. Bioresour Technol. 2015;175:396-405.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biogas potential from spent tea waste: A laboratory scale investigation of co-digestion with cow manure. Energy. 2018;165(2018):76. 760e768

- [Google Scholar]

- A list of marine algae from Australia and Tasmania. Acta Horti Gothoburg. 1946;16:215-227.

- [Google Scholar]

- A strategy for understanding the enhanced anaerobic co-digestion via dual-heteroatom doped bio-based carbon and its functional groups. Chem. Eng. J.. 2021;425:130473

- [Google Scholar]

- Anaerobic hydrolysis and fermentation of fats and proteins. In: Zehnder A.J.B., ed. Biology of Anaerobic Microorganisms. New York: Wiley; 1998.

- [Google Scholar]

- Titration of ammonia in the presence of boric acid. Ind. Eng. Chem., Anal. Ed.. 1933;5:396.

- [Google Scholar]

- Estimation of maturity of compost from food wastes and agro-residues by multiple regression analysis. Bioresource Technology. 2006;97:1979-1985.

- [Google Scholar]

- Carbon and Nitrogen Dynamics, and CO2 Efflux in the Calcareous Sandy Loam Soil Treated with Chemically Modified Organic Amendments. Molecules. 2021;26:4707.

- [Google Scholar]

- Microalgae as substrates for fermentative biogas production in a combinedbiorefinery concept. J. Biotechnol.. 2010;150:51-56.

- [Google Scholar]

- Microalgae as substrates for fermentative biogas production in a combined biorefinery concept. J Biotechnol. 2010;150:51-56.

- [Google Scholar]

- Influence of hydrothermal pretreatment on microalgal biomass anaerobic digestion and bioenergy production. Water Res.. 2014;68:364-373.

- [Google Scholar]

- Optimizing biomethane production from anaerobic degradation of Scenedesmus spp. biomass harvested from algae-based swine digestate treatment. Int Biodeterior. Biodegradation. 2016;109:23-28.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cleaner production of agriculturally valuable benignant materials from industry generated bio-wastes: A review. Bioresour Technol.. 2021 Jan;320(Pt A):124281

- [Google Scholar]

- The Effects of Hot Water and Ultrasonication Pretreatment of Microalgae (Nannochloropsis oculata) on Biogas Production in Anaerobic Co-Digestion with Cow Manure. Processes. 2020;8:1558.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cultivation of blue green algae (Arthrospira plantensis Gomant, 1892) in wastewater for biodiesel production. Chemosphere. 2023;335:139107

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of composting on phytotoxicity of spent pig-manure sawdust litter. Environ.Pollut.. 1996;93:249-256.

- [Google Scholar]

- A Review on Current Trends in Biogas Production from Microalgae Biomass and Microalgae Waste by Anaerobic Digestion and Co-digestion. Bioenerg. Res.. 2022;15:77-92.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biogas Production from Microalgae (spirulina Platensis) in a Two Stage Anaerobic System. Waste and Biomass Valorization [internet]. 2016;7:193-200. [cited 2022 Feb

- Mesophilic anaerobic co-digestion of acorn slag waste with dairy manure in a batch digester: Focusing on mixing ratios and bio-based carbon accelerants. Bioresource Technology. 2019;286:121394

- [Google Scholar]

- Binary and ternary trace elements to enhance anaerobic digestion of cattle manure: Focusing on kinetic models for biogas production and digestate utilization. Bioresource Technology. 2021;323:124571

- [Google Scholar]

- Use of bag-filter gas dust in anaerobic digestion of cattle manure for boosting the methane yield and digestate utilization. Bioresource Technology. 2022;348:126729

- [Google Scholar]

- Improving performance and phosphorus content of anaerobic co-digestion of dairy manure with aloe peel waste using vermiculite. Bioresource Technology. 2020;301:122753

- [Google Scholar]

- Concentrated biogas slurry enhanced soil fertility and tomato quality. Acta Agriculturae Scandinavica Section B_Soil and Plant. Science. 2010;60:262_268.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mineral residue accelerant-enhanced anaerobic digestion of cow manure: an evaluation system of comprehensive performance. Sci. Total Environ.. 2023;858:159840

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of biogas slurry pretreatment on germination and seedling growth of Vicia faba L. Adv. Mat. Res.. 2014;955–959:208-212.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of biogas slurry application on peanut yield, soil nutrients, carbon storage, and microbial activity in an Ultisol soil in southern China. J. Soil. Sediment.. 2016;2016(16):449-460.

- [Google Scholar]

Appendix A

Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2024.103380.

Appendix A

Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article: