Translate this page into:

An assessment of occupational effective dose in several medical departments in Saudi Arabia

⁎Address: King Saud University, Riyadh 11451, Saudi Arabia Yalashban@ksu.edu.sa (Yazeed Alashban)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Purpose

To assess occupational effective dose in fourteen different medical departments in Saudi Arabia during 2018–2019.

Methods

Thermoluminescent dosemeters (TLD-100) made of Harshaw detector crystal of LiF:Ti,Mg were used to estimate effective doses for 1,375 medical workers. These TLDs are made of Harshaw detector crystal of LiF:Ti,Mg with an estimated tissue equivalence (Zeffective) of 8.15 and density of 2.65 g/cm3. TLDs were analyzing using Harshaw model 6600 plus TLD reader along with WinREMS software.

Results

The annual mean effective doses for the workers in 2018 and 2019 remained in the range of 0.27–0.96 and 0.34–1.24 mSv respectively. The annual collective doses for all workers in 2018 and 2019 were found to be 591 and 847 person-mSv respectively. More than 93% of the workers received an effective dose of less than 1 mSv. A comparison of occupational dose values among the studied departments revealed that workers in the nuclear medicine and cardiac catheterization exposed to the highest annual effective doses.

Conclusion

In compliance with the ALARA principle, the occupational doses were distributed with a low dose range in mind. In general, the dose values for this study are an indication of an adequative radiation practices mainly due to reducing radiation leakage by using better manufacturing equipment, improving the effective radiation protection policies, developing a highly effective radiation protection equipments, and having access to the latest radiology literature.

Keywords

Dose limit

Effective dose

Radiation protection

Occupational exposure

Ionizing radiation

- IAEA

-

International Atomic Energy Agency

- ICRP

-

International Commission on Radiological Protection

- MOH

-

Saudi Ministry of Health

- RPP

-

Radiation Protection Program

- TLD

-

Thermoluminescent dosimeter

- KFMC

-

King Fahad Medical City

- OR

-

Operation room

- Cath Lab

-

Cardiac catheterization lab

- CSD

-

Communication and swallowing disorders

- ER

-

Emergency

- DR

-

Diagnostic radiology

- IR

-

Interventional radiology

- NM

-

Nuclear medicine

- MP

-

Medical physics

- OBGYN

-

Obstetrics and gynecology

- RT

-

Radiotherapy

- SE

-

standard error

- ANOVA

-

An analysis of the variance test

- ALARA

-

As low as reasonably achievable

Abbreviations

1 Introduction

It is critical to apply protective and preventive measures when dealing with ionization radiation for medical procedures. Otherwise, medical workers and patients shall be exposed to a high amount of radiation, which will lead to dangerous health effects such as cataract development and cancer (IAEA, 2014; Venneri et al., 2009; Ciraj‐Bjelac et al., 2010; Fazel et al., 2009; Muirhead et al., 2009). An occupationally exposed worker is a term that refers to an employee who is exposed to ionization radiation from their work place. The radiation dose is estimated by measuring the collective radiation exposure received by the employee (Szewczak et al., 2013).

The International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP) provides recommendations regarding the radiation protection practices for ionizing radiation, including dose limits for medical staff. The ICRP publication 103 recommends taking all practical efforts to keep the radiation exposure as low as is reasonably achievable (ALARA) (IAEA, 1996). This is the essential principle for radiation protection. Internationally, medical radiation workers account for around 50% of the exposed population to ionizing radiation (ICRP, 1991). Radiation monitoring is the key tool in radiation protection practices to estimate the occupational radiation dose (Bhatt et al., 2008). In order to assess radiation risks and create protective measures, most governments and organizations require an estimated occupational dose for workers who receive more than 10% of radiation dose limit (Muhogora et al., 2013; Tian et al., 2008; UNSCEAR, 2000).

In Saudi Arabia, the Radiation Protection Program (RPP) of the Ministry of Health (MOH) has been in place since 1986. Its mission is to provide protection to workers, patients, and the public from the risks of ionizing radiation exposure (Mora and Acuna, 2011). Further, the RPP is responsible for measuring and analyzing the personal radiation dosemeters for all workers in all healthcare facilities affiliated with the Ministry in various regions of the Kingdom.

According to the 2014 report by the IAEA on Radiation Protection and Safety of Radiation Sources: International Basic Safety Standards, Hp (10) represents the deep dose (whole-body), Hp (0.07) represents the shallow dose (skin/extremities), and Hp (3) represents eye lens dose (IAEA, 2014).

King Fahad Medical City (KFMC), established in 2004 and working under the umbrella of the Ministry of Health, is the largest medical city in Saudi Arabia and is located in Riyadh. It has four specialized hospitals and four subspecialized centers. KFMC contains the main hospital, a children’s specialized hospital, a women’s specialized hospital, and a rehabilitation hospital. Furthermore, it has a national neurosciences institute, the King Salman health center, a comprehensive cancer center, and an obesity, endocrine, and metabolism center (ICRP, 2012). Annually, KFMC has the capability to treat more than 50,000 inpatients and more than 2,000,000 outpatients (KFMC, 2020).

2 Materials and methods

A retrospective study was carried out on the occupational radiation dose for 1,375 medical workers in King Fahad Medical City during 2018–2019. These workers occupied the following departments: operation room (OR), cardiac catheterization lab (Cath Lab), communication and swallowing disorders (CSD), dentistry, emergency (ER), endoscopy, diagnostic radiology (DR), interventional radiology (IR), nuclear medicine (NM), medical physics (MP), obstetrics and gynecology (OBGYN), radiotherapy (RT), gastroenterology, and urology.

A whole-body thermoluminescent dosemeters (TLDs) were assigned to all the workers with a bar-coded number that represented their identity and their period of use. The workers were recommended to wear the TLD under their lead apron on their upper torso, in order to reflect the whole-body dose. These TLDs (TLD-100) are made of Harshaw detector crystal of LiF:Ti,Mg with an estimated tissue equivalence (Zeffective) of 8.15 and density of 2.65 g/cm3. For calibration and quality control (QC) analysis, 90Sr/90Y, with a radiation activity of 0.50 mCi, was used. Every three months, the RPP in KFMC is responsible for collecting the TLDs and analyzing them using Harshaw model 6600 plus TLD reader (Thermo Electron Corporation, Ohio, USA) along with WinREMS software. The reader had a sensitivity range of 10 μGy to 1 Gy, with a linearity of less than 5%. The preheated temperature of the time temperature profile was 120 °C with an acquisition temperature rate of 20 °C/s up to 350° C. The reading system utilized a purified nitrogen supply at a pressure range of 35 to 95 psi, with an ideal flow rate mode of 28 l/h (1 scfh). The radiation protection department in KFMC is responsible for reporting these results to the radiation protection program (RPP) in the Ministry of Health. The TLD readings were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) Software, Version 20 (SPSS‑Inc., Chicago, IL) at a 95% confidence interval.

3 Results

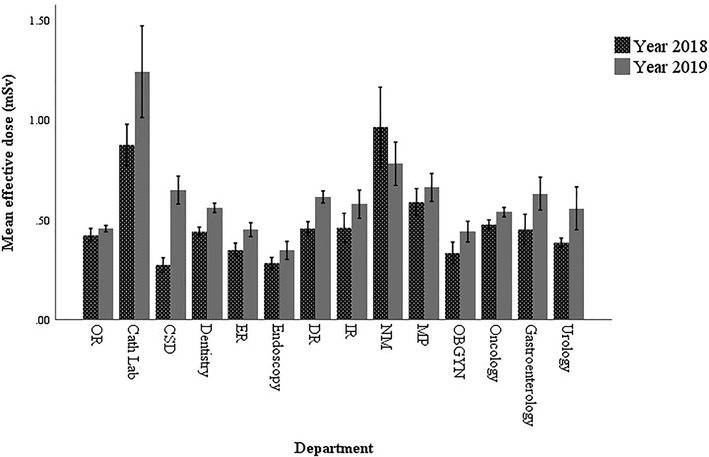

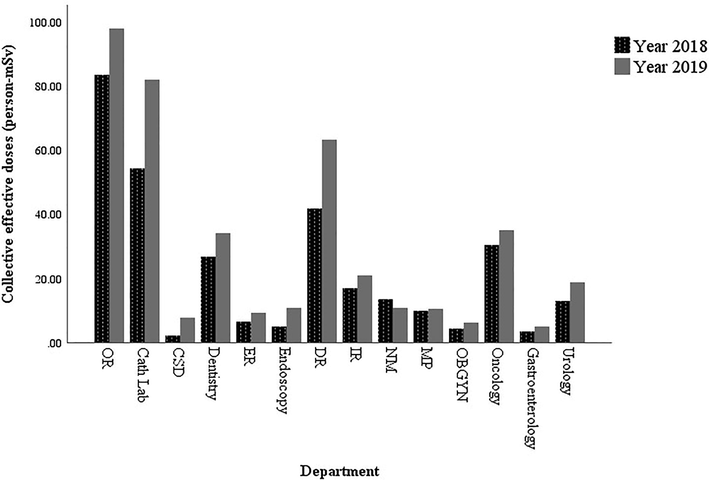

TLDs were used to monitor 660 and 715 medical workers in 2018 and 2019 respectively. The number of workers in each department is listed in Table 1. In both years, the highest number of workers were within the operation room department, followed by the diagnostic radiology department. The mean effective dose is an indicator of which of these medical departments’ workers were exposed to the highest radiation exposure. Fig. 1 illustrates the mean effective doses for all the medical departments’ workers in 2018 and 2019. Similarly, Fig. 2 shows the collective effective doses for all the medical departments’ workers during the study period. The annual collective doses for all workers in 2018 and 2019 were found to be 591 and 847 person-mSv respectively.

Medical Department

Workers in 2018

Workers in 2019

Operation Room

197

215

Cath Lab

77

66

CSD

8

12

Dentistry

61

61

Emergency

19

21

Endoscopy

18

51

DR

93

102

IR

37

36

NM

14

14

MP

17

16

OBGYN

13

14

RT

64

65

Gastroenterology

8

8

Urology

34

34

Total number of workers

665

715

Mean effective doses for all the medical departments’ workers in 2018 and 2019.

Collective effective doses for all the medical departments’ workers in 2018 and 2019.

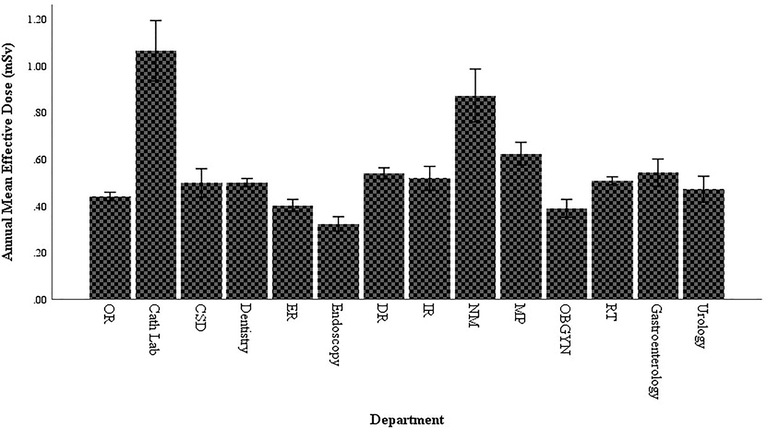

The annual mean effective doses for the workers in 2018 and 2019 remained in the range of 0.27–0.96 and 0.34–1.24 mSv respectively. The annual mean effective dose (averaged over the study period) is shown in Fig. 3. The results show that workers in the cardiac catheterization department received the highest effective dose average over the study period, followed by the nuclear medicine workers.

The annual mean effective dose (averaged over 2018 and 2019) for all the medical departments.

4 Discussion

In 2018, the comparison of mean effective dose values among the studied departments revealed that the highest values lie within the nuclear medicine workers, followed by the cardiac catheterization workers. In 2019, the cardiac catheterization personnel received the highest mean effective dose, followed by the nuclear medicine personnel. Unlike other medical workers, nuclear medicine personnel handle a large amount of radioactive material, with a radiation activity in the order of GBqs. This usually happens when they use unsealed radioactive sources and during the radiopharmaceutical preparation. Moreover, they remain in very close proximity to the patients during radiopharmaceutical injections. Likewise, the occupational dose during the cardiac catheterization procedures is relatively high due to the presence of the workers besides the patients while the x-ray beam is “on” for a long period of time. These factors account for the increase in the radiation dose among the nuclear medicine and the cardiac catheterization workers compared to the other medical workers in other departments. However, the results showed that no single occupational dose exceeded the annual dose limit of 20 mSv in any of the fourteen departments during 2018–2019.

An analysis of the variance test (one-way ANOVA) was performed to find out if there were statistically significant differences in the mean effective doses between each departments’ workers. The test reveals statistically significant differences in the mean effective doses between the departments’ workers in 2018 (F (13,630) = 6.58, p = 0.00) and in 2019 (F (13,682) = 6.65, p = 0.00).

The results show an increase in the annual mean effective dose from 2018 to 2019 by 22% mainly due to the increase of radiation procedures. To assess the significance of this increase, the annual mean effective dose in both years were statistically compared using a two-tailed independent sample t-test at α = 0.05. The results suggest that the annual mean effective dose in 2018 (M = 0.48, SD = 0.45) are significantly less than the annual mean effective dose in 2019 (M = 0.59, SD = 0.67), t (1378) = 3.42, p = 0.001.

The comparative analysis of mean effective annual doses in diagnostic radiology, nuclear medicine, and radiotherapy is illustrated in Table 2. Regardless of the differences in the data range, the table provides a rough assessment of the occupational radiation dose. In general, the dose values for this study are an indication of improved radiation practices when compared studies conducted in previous years. This is mainly due to many factors, such as: reducing radiation leakage by using better manufacturing equipment, improving the effective radiation protection policies, developing a highly effective radiation protection equipments, and having access to the latest radiology literature (Linet et al., 2010). These implemented factors considerably reduced the annual doses making KFCM a reference center for the radiation safety practice in Saudi Arabia.

Data range

Country

DR (mSv)

NM (mSv)

RT (mSv)

2000–2002

Canada

0.75

2.11

0.76

2000–2002

Chile

4.39

14.78

2.40

1992–1994

Kuwait

1.56

0.96

1.35

1996–2000

China

1.50

1.20

0.90

1997–1998

Greece

2.72

1.82

3.63

2007–2011

Pakistan

0.52

1.12

0.88

2018–2019

Current study

0.53

0.62

0.50

The only limitation of this study is that it did not specify the effective dose for each occupational group (i.e., radiologists, technologists, nurses, or medical assistants). This mainly due to that the database of the RPP does not include the occupational position for all medical workers. Starting from 2020, RPP will update its policy to include the occupational position of each worker in their database. For future work, a study of the equivalent dose for the skin, hands/feet and lens of the eye would offer a comprehensive overview of the radiation safety practices in Saudi Arabia.

5 Conclusion

This study aimed to provide an indication of the effective dose values for medical workers in Saudi Arabia. During the study period, all the workers received occupational doses below the annual effective dose limit. In compliance with the ALARA principle, the occupational doses were distributed with a low dose range in mind. More than 93% of the workers received an annual effective dose of less than 1 mSv. Among the fourteen different medical departments, workers in the nuclear medicine and cardiac catheterization exposed to the highest annual effective doses. These results are an excellent indicator of the radiation safety practices in Saudi Arabia.

Acknowledgement

Author extend his appreciation to the College of Applied Medical Sciences Research Center and Deanship of Scientific Research at King Saud University for funding this project.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Bhatt, C.R., Widmark, A., Shrestha, S.L., Khanal, T. and Ween, B., 2008. Occupational radiation exposure monitoring among radiation workers in Nepal. Proceedings of the 12th Congress of the International Radiation Protection Association; 2008 Oct 19-24; Buenos Aires, IRPA 12- INIS-ARC-1194, 19–24.

- Risk for radiation-induced cataract for staff in interventional cardiology: Is there reason for concern? Catheter Cardio. Inte.. 2010;76:826-834.

- [Google Scholar]

- Exposure to low-dose ionizing radiation from medical imaging procedures. New Engl. J. Med.. 2009;361:849-857.

- [Google Scholar]

- IAEA, 1996. International basic safety standards for protection against ionizing radiation and for safety of radiation sources. Safety Series No. 115, 1–30.

- ICRP, 1991. 1990 recommendations of the International Commission on Radiological Protection, Ann. ICRP. 60, 2–4.

- ICRP, 2012. ICRP statement on tissue reactions and early and late effects of radiation in normal tissues and organs–threshold doses for tissue reactions in a radiation protection context. Ann. ICRP, 01−322.

- IAEA, 2014. Radiation Protection and Safety of Radiation Sources: International Basic Safety Standards. Safety Standards Series No. GSR Part 3, 1–30.

- Occupational exposure to ionising radiation in Greece (1994–1998) Radiat. Prot. Dosimetry. 2000;91:385-389.

- [Google Scholar]

- King Fahad Medical City (KFMC). Hospitals and Centers. Available at: www.kfmc.med.sa/pages/home.aspx. (accessed 10th August 2020).

- Historical review of occupational exposures and cancer risks in medical radiation workers. Radiat. Res.. 2010;174:793-808.

- [Google Scholar]

- Muirhead, C.R., O'hagan, J.A., Haylock, R.G.E., Phillipson, M.A., Willcock, T., Berridge, G.L.C., Zhang, W., 2009. Mortality and cancer incidence following occupational radiation exposure: third analysis of the National Registry for Radiation Workers. Brit. J Cancer 100, 206–212.

- Assessment of medical occupational radiation doses in Costa Rica. Radiat. Prot. Dosimetry. 2011;147:230-232.

- [Google Scholar]

- Masood, K., Ahmad, M., Zafar, J., ul Haq, M., Ashfaq, A., Zafar, H., 2012. Assessment of occupational exposure among Pakistani medical staff during 2007–2011. Australas. Phys. Eng. Sci. Med. 35, 297–300.

- Occupational radiation exposure in Tanzania (1996–2010): status and trends. Radiat. Prot. Dosimetry. 2013;153:403-410.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rasooldeen M. Abdullah Opens Fahd Medical City. Available at: www.arabnews.com/node/256188. (accessed 22nd August 2020).

- Individual dose monitoring of the nuclear medicine departments staff controlled by Central Laboratory for Radiological Protection. Nucl. Med. Rev. Cent. East. Eur.. 2013;16:62-65.

- [Google Scholar]

- Saudi Ministry of Health (MOH). 4 Radiation Protection Units to be Established. Available at: https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Ministry/MediaCenter/News/Pages/News-2013-08-26-002.aspx (accessed 10th August 2020).

- Dose level of occupational exposure in China. Radiat. Prot. Dosimetry. 2008;128:491-495.

- [Google Scholar]

- UNSCEAR, 2000. Sources and effects of ionizing radiation. UNSCEAR report 2000 to the general assembly of the United Nations with scientific annexes, New York.

- Sources and effects of ionizing radiation. Vol Volume I. New York: United Nations; 2008.

- Cancer risk from professional exposure in staff working in cardiac catheterization laboratory: insights from the National Research Council’s Biological Effects of Ionizing Radiation VII Report. Am. Heart J.. 2009;157:118-124.

- [Google Scholar]

- Occupational exposures of Chinese medical radiation workers in 1986–2000. Radiat. Prot. Dosimetry. 2005;117:440-443.

- [Google Scholar]