Translate this page into:

A new one-parameter discrete exponential distribution: Properties, inference, and applications to COVID-19 data

⁎Corresponding authors. ahmed.afify@fcom.bu.edu.eg (Ahmed Z. Afify), hector.gomez@uantof.cl (Héctor W. Gómez)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

A new one-parameter discrete length-biased exponential distribution called the discrete moment exponential (DMEx) distribution is introduced using the survival discretizing approach. We derive the reliability measures including survival function, hazard function, residual reliability function, and the second rate of failure function. Further, the mathematical properties of the DMEx distribution are derived. The parameters of the DMEx distribution are estimated using seven estimation methods. A simulation study is carried out to explore the behavior of the proposed estimators. It is observed that the maximum likelihood approach provides efficient estimates. Finally, the DMEx is adopted for fitting the number of COVID-19 deaths in China and Europe countries. It is shown that the DMEx distribution fits the data better than other competing discrete distributions.

Keywords

Discretization method

Simulation

Statistical inference

Data analysis

COVID-19

1 Introduction

In the last decades, several discrete distributions have been introduced as analogs of the continuous distributions to have a better alternative model for modeling count data sets having complicated behavior. Although classical models such as binomial, Poisson, Geometric, and negative binomial distributions are used to model count data sets, in some situations, these probability models do not provide the best fit. Hence there is a need to develop more flexible distributions.

Several discretization methods have been adopted extensively in the literature to define new discrete models. Chakraborty (Chakraborty, 2015) conducted a survey on several discretization methods available to derive discrete analogs of continuous distributions, such as discretization methods based on survival function (SF), probability density function (PDF), cumulative distribution function (CDF), hazard rate function (HRF), reversed-HRF, the difference equation analog of Persian differential equation and a two-stage composite method.

Let a random variable (rv)

follows a continuous probability distribution with SF

. Using the SF discretization method which is introduced by Kemp (2004), the probability mass function (PMF) of a discrete rv is specified by.

Using this method of discretization several discrete distribution have been introduced, such as the discrete Weibull (Nakagawa and Osaki, 1975), discrete Rayleigh (Roy, 2004), discrete half-normal (Kemp, 2008), discrete Burr and discrete Pareto (Krishna and Singh Pundir, 2009), discrete inverse-Weibull (Jazi et al., 2010), generalized geometric (Gómez-Déniz, 2010), discrete Lindley (Gomez-Deniz and Calderin-Ojeda, 2011), generalized exponential type II (Nekoukhou et al., 2013), two-parameter discrete Lindley (Hussain et al., 2016), new discrete extended-Weibull (Jia et al., 2019), natural discrete-Lindley (Al-Babtain et al., 2020); discrete MO-Weibull (Opone et al., 2020), uniform Poisson–Ailamujia (Aljohani et al., 2021), discrete inverted Topp-Leone (Eldeeb et al., 2021), discrete power-Ailamujia (Alghamdi et al., 2022), Binomial-exponential 2 (Bakouch et al., 2017), Poisson-exponential (Rodrigues et al., 2018), and discrete Ramos-Louzada (Ramos and Louzada, 2019; Afify et al., 2021).

Dara and Ahmad (2012) introduced the moment-exponential (MEx) distribution and showed that it is more flexible than the exponential distribution. The PDF of MEx distribution is specified by.

The corresponding SF has the form

Using the discretization method based on the SF, a discrete analog of continuous MEx distribution is introduced in this paper.

In this article, we propose the asymmetric discrete distribution called the discrete moment exponential (DMEx) distribution using the discretization method based on SF. The DMEx distribution is a competitor to some well-known discrete models such as the discrete Burr, discrete Burr-Hatke, discrete Rayleigh, discrete inverted Topp-Leon, discrete Pareto, discrete inverse Rayleigh, and Poisson distributions. The parameter of the DMEx model is estimated using seven classical estimation approaches. We present the detailed simulation results to address the behavior of the estimators.

The rest of this paper is outlined six sections. In Section 2, we define the new DMEx distribution and provide some of its basic properties. The estimation approaches are presented in Section 3. The efficiency of the introduced estimators is assessed via simulation results in Section 4. Section 5 provides two real applications to COVID-19 data of the DMEx distribution. Section 6 presents some final conclusions.

2 The DMEx distribution and its properties

The DMEx distribution is obtained using Eqs. (1) and (3). The PMF of the DMEx distribution has the form (for

)

The corresponding CDF of the DMEx model reduces to

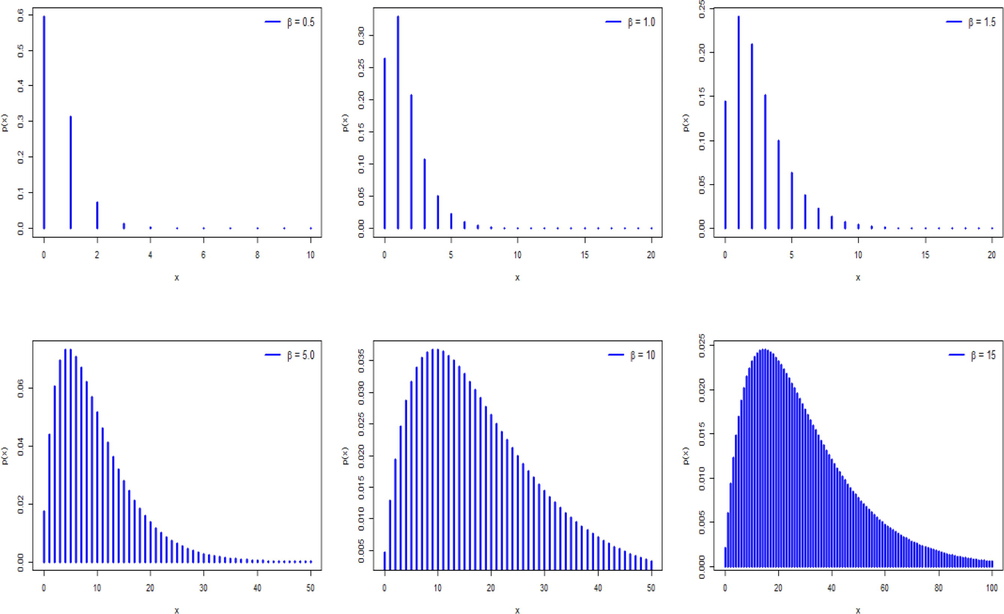

Fig. 1 shows the PMF behavior of the DMEx distribution for different values of

. It is observed that the DMEs PMF has unimodal behavior and positively skewed for

. The mode of the DMEx distribution moves towards the left for large values of

.

The PMF plots of the DMEx distribution.

2.1 Survival, hazard rate, and quantile functions

The SF of the DMEx distribution reduces to

The HRF of the DMEx distribution takes the form

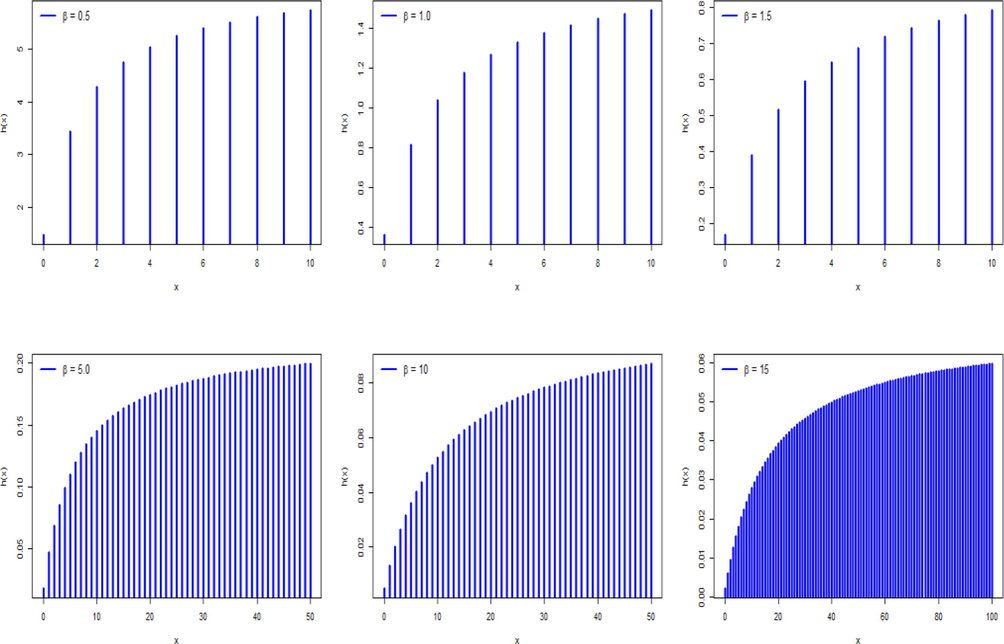

Fig. 2 shows that the behavior of the HRF of the DMEx model is increasing for different values of

.

The HRF plots of the DMEx distribution.

The second rate of failure, say , of the DMEs model is defined as.

The reversed HRF of the DMEx distribution is

The quantile function (QF) of the DMEx model takes the form where is the integer part of and is the negative branch of the Lambert function.

2.2 Probability generating function and moments

The probability generating function of the DMEx distribution follows as

Differentiating with respect to and setting , we can obtain the first four factorial moments of the DMEx distribution as follows

The first four ordinary moments of the DMEx distribution can be calculated using the factorial moments as follows

The variance of the DMEx distribution has the form

Further, the coefficient of skewness and kurtosis of the DMEx distribution can be calculated by the formulae and

2.3 Dispersion index

The index of dispersion (DI) is defined as

The DI shows that whether a distribution is suitable for modeling under-dispersed data or over-dispersed data. The distribution is over-dispersed for

and for

it is under-dispersed. Table 1 reports some numerical values for the descriptive measures of the DMEx distribution. Table 1 shows that the DMEs model is useful for both over-dispersed and under-dispersed data sets. The DMEx also exhibits positively skewed which supported by the plots of its PMF in Fig. 1.

Parameter

Descriptive Measures

β

Mean

Variance

Skewness

Kurtosis

DI

0.2

0.0409

0.0403

4.8256

25.763

0.9839

0.5

0.5185

0.5253

1.5011

11.266

1.0130

0.8

1.1050

1.3364

1.3678

18.932

1.2093

1.0

1.5027

2.0653

1.3668

23.323

1.3745

1.5

2.5008

4.5750

1.3838

31.074

1.8294

2.0

3.5003

8.0786

1.3950

35.852

2.3079

2.5

4.5002

12.580

1.4013

39.022

2.7955

3.0

5.5001

18.081

1.4049

41.263

3.2874

4.0

7.5000

32.082

1.4089

44.209

4.2776

5.0

9.5000

50.083

1.4108

46.052

5.2718

9.0

17.500

162.08

1.4131

49.473

9.2618

3 Parameter estimation

In this section, we estimate the parameter of the DMEx distribution using seven methods of estimation.

3.1 Maximum likelihood (ML)

Suppose be a random sample of size from the DMEx distribution. Then, the log-likelihood function reduces to

The ML estimator (MLE) of follows by solving that is

The MLE of cannot be calculated explicitly. Hence, numerical methods can be adopted to obtain it.

3.2 Methods of Anderson-Darling and right-tail Anderson-Darling

Let be the th order statistic in a sample of size . The Anderson-Darling (AD) test is proposed by (Anderson and Darling, 1952). Let be the AD estimator (ADE) which is obtained by minimizing the following equation

This estimator of

can also be derived by solving

where

and it reduces to

The right-tail Anderson-Darling (RADE) of the parameter follows by minimizing

The RADE is also calculated by solving

3.3 Method of Cramèr-von-Misses

Macdonald (Macdonald, 1971) proved that the Cramèr-von-Mises estimator (CVME) has a smaller bias as compared to other minimum distance type estimators. The CVME of follows by minimizing

The CVME of is also obtained by solving

3.4 Methods of least-squares and weighted least-squares

The least-squares estimator (LSE) of follows by minimizing with respect to . Moreover, the LSE of is also obtained by solving

The weighted least-squares estimator (WLSE) of follows by minimizing

The WLSE of can also be obtained by solving

In which is presented in (6).

3.5 Methods of percentiles

Suppose that is an unbiased estimator of . Hence, the percentiles estimator (PCE) (Kao, 1959) of the parameter can be derived by minimizing the following equation where is the negative branch of the Lambert function.

4 Simulation study

Here we conduct a Monte Carlo simulation study to compare the performance of different methods of estimation. The performance of different estimators is evaluated based on mean square errors (MSEs), mean relative errors (MREs) and average absolute biases (ABBs) which are given by. and

The introduced methods are compared for sample sizes,

=5, 10, 30, 50, and 100. To this end, we generate 10,000 independent samples of size

from the DMEx distribution with different values of

= 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 5.0 and 9.0. It is observed that 10,000 repetitions are sufficiently large enough to have stable results. The results of the simulations are reported in Tables 2–4.

Measure

MLE

LSE

WLE

PCE

CVME

ADE

RADE

10

AABs

0.0588

0.3887

0.4145

0.2315

0.3888

0.3826

0.3710

25

0.0169

0.3879

0.4427

0.2022

0.3878

0.3792

0.3678

50

0.0032

0.3874

0.4650

0.1888

0.3874

0.3797

0.3665

100

0.0012

0.3878

0.4838

0.1808

0.3877

0.3791

0.3662

150

0.0007

0.3870

0.4945

0.1777

0.3876

0.3792

0.3656

200

0.0009

0.3872

0.5022

0.1752

0.3875

0.3790

0.3656

10

MREs

0.2354

1.5546

1.6581

0.9259

1.5551

1.5305

1.4840

25

0.0677

1.5518

1.7708

0.8087

1.5511

1.5168

1.4712

50

0.0128

1.5497

1.8601

0.7551

1.5497

1.5189

1.4659

100

0.0047

1.5511

1.9350

0.7232

1.5507

1.5166

1.4649

150

0.0029

1.5481

1.9780

0.7106

1.5503

1.5166

1.4624

200

0.0037

1.5488

2.0088

0.7008

1.5501

1.5159

1.4624

10

MSEs

0.0198

0.1530

0.1756

0.0586

0.1531

0.1480

0.1386

25

0.0058

0.1512

0.1980

0.0430

0.1511

0.1443

0.1356

50

0.0014

0.1505

0.2172

0.0366

0.1505

0.1445

0.1344

100

0.0006

0.1506

0.2345

0.0332

0.1505

0.1439

0.1342

150

0.0004

0.1499

0.2449

0.0319

0.1503

0.1439

0.1337

200

0.0003

0.1500

0.2526

0.0309

0.1503

0.1437

0.1337

10

AABs

0.0051

0.3368

0.3715

0.2471

0.3371

0.3290

0.2983

25

0.0004

0.3306

0.3995

0.2117

0.3313

0.3224

0.2888

50

0.0011

0.3311

0.4241

0.1940

0.3294

0.3197

0.2864

100

0.0010

0.3290

0.4484

0.1835

0.3295

0.3189

0.2848

150

0.0001

0.3289

0.4633

0.1783

0.3289

0.3180

0.2841

200

0.0000

0.3285

0.4745

0.1758

0.3290

0.3181

0.2834

10

MREs

0.0103

0.6735

0.7429

0.4941

0.6741

0.6579

0.5966

25

0.0007

0.6611

0.7989

0.4234

0.6627

0.6448

0.5777

50

0.0022

0.6622

0.8482

0.3881

0.6587

0.6395

0.5729

100

0.0019

0.6580

0.8967

0.3670

0.6590

0.6377

0.5696

150

0.0002

0.6578

0.9266

0.3567

0.6578

0.6361

0.5682

200

0.0001

0.6570

0.9490

0.3517

0.6580

0.6362

0.5667

10

MSEs

0.0161

0.1271

0.1492

0.0795

0.1268

0.1222

0.1014

25

0.0058

0.1145

0.1639

0.0515

0.1149

0.1094

0.0885

50

0.0030

0.1123

0.1821

0.0409

0.1111

0.1048

0.0844

100

0.0015

0.1095

0.2022

0.0353

0.1098

0.1030

0.0823

150

0.0010

0.1090

0.2155

0.0329

0.1090

0.1020

0.0815

200

0.0007

0.1086

0.2258

0.0317

0.1089

0.1019

0.0809

Measure

MLE

LSE

WLE

PCE

CVME

ADE

RADE

10

AABs

0.0088

0.3362

0.3488

0.2921

0.3359

0.3348

0.2916

25

0.0011

0.3259

0.3496

0.2346

0.3230

0.3182

0.2750

50

0.0016

0.3197

0.3672

0.2140

0.3159

0.3099

0.2673

100

0.0009

0.3171

0.3847

0.1951

0.3185

0.3116

0.2643

150

0.0008

0.3154

0.3986

0.1884

0.3145

0.3074

0.2645

200

0.0001

0.3152

0.4066

0.1848

0.3146

0.3074

0.2620

10

MREs

0.0088

0.3362

0.3488

0.2921

0.3359

0.3348

0.2916

25

0.0011

0.3259

0.3496

0.2346

0.3230

0.3182

0.2750

50

0.0016

0.3197

0.3672

0.2140

0.3159

0.3099

0.2673

100

0.0009

0.3171

0.3847

0.1951

0.3185

0.3116

0.2643

150

0.0008

0.3154

0.3986

0.1884

0.3145

0.3074

0.2645

200

0.0001

0.3152

0.4066

0.1848

0.3146

0.3074

0.2620

10

MSEs

0.0502

0.1755

0.1768

0.1498

0.1740

0.1708

0.1388

25

0.0201

0.1305

0.1429

0.0799

0.1274

0.1233

0.0959

50

0.0105

0.1143

0.1442

0.0583

0.1116

0.1074

0.0819

100

0.0052

0.1065

0.1521

0.0439

0.1073

0.1028

0.0751

150

0.0035

0.1034

0.1617

0.0395

0.1028

0.0983

0.0734

200

0.0026

0.1023

0.1674

0.0372

0.1021

0.0975

0.0711

10

AABs

0.0038

0.3618

0.3741

0.3855

0.3511

0.3566

0.3139

25

0.0047

0.3243

0.3399

0.2932

0.3221

0.3216

0.2730

50

0.0011

0.3231

0.3428

0.2427

0.3222

0.3187

0.2674

100

0.0002

0.3194

0.3410

0.2201

0.3149

0.3103

0.2583

150

0.0002

0.3167

0.3449

0.2017

0.3136

0.3092

0.2558

200

0.0019

0.3115

0.3472

0.1960

0.3129

0.3081

0.2524

10

MREs

0.0019

0.1809

0.1870

0.1928

0.1756

0.1783

0.1570

25

0.0023

0.1621

0.1700

0.1466

0.1611

0.1608

0.1365

50

0.0005

0.1616

0.1714

0.1213

0.1611

0.1594

0.1337

100

0.0001

0.1597

0.1705

0.1100

0.1575

0.1552

0.1292

150

0.0001

0.1583

0.1724

0.1009

0.1568

0.1546

0.1279

200

0.0010

0.1557

0.1736

0.0980

0.1565

0.1541

0.1262

10

MSEs

0.1982

0.3722

0.3850

0.4017

0.3602

0.3516

0.3187

25

0.0782

0.1980

0.2090

0.1805

0.1976

0.1920

0.1568

50

0.0411

0.1524

0.1615

0.1069

0.1519

0.1470

0.1141

100

0.0201

0.1253

0.1374

0.0720

0.1223

0.1181

0.0876

150

0.0134

0.1160

0.1330

0.0560

0.1142

0.1106

0.0793

200

0.0099

0.1083

0.1306

0.0506

0.1097

0.1061

0.0741

Measure

MLE

LSE

WLE

PCE

CVME

ADE

RADE

10

AABs

0.0130

0.3975

0.4179

0.4705

0.3643

0.3769

0.3574

25

0.0014

0.3498

0.3519

0.3383

0.3386

0.3420

0.2850

50

0.0097

0.3335

0.3295

0.2823

0.3243

0.3245

0.2559

100

0.0003

0.3206

0.3306

0.2340

0.3168

0.3147

0.2509

150

0.0060

0.3175

0.3288

0.2218

0.3119

0.3100

0.2496

200

0.0037

0.3126

0.3289

0.2095

0.3114

0.3088

0.2447

10

MREs

0.0043

0.1325

0.1393

0.1568

0.1214

0.1256

0.1191

25

0.0005

0.1166

0.1173

0.1128

0.1129

0.1140

0.0950

50

0.0032

0.1112

0.1098

0.0941

0.1081

0.1082

0.0853

100

0.0001

0.1069

0.1102

0.0780

0.1056

0.1049

0.0836

150

0.0020

0.1058

0.1096

0.0739

0.1040

0.1033

0.0832

200

0.0012

0.1042

0.1096

0.0698

0.1038

0.1029

0.0816

10

MSEs

0.4482

0.7108

0.7379

0.7991

0.6734

0.6494

0.6324

25

0.1827

0.3402

0.3251

0.3305

0.3274

0.3155

0.2765

50

0.0859

0.2208

0.2068

0.1883

0.2129

0.2063

0.1631

100

0.0451

0.1558

0.1590

0.1079

0.1534

0.1489

0.1090

150

0.0305

0.1364

0.1401

0.0846

0.1327

0.1292

0.0942

200

0.0224

0.1234

0.1315

0.0704

0.1239

0.1207

0.0843

10

AABs

0.0021

0.4191

0.4318

0.6349

0.4216

0.4438

0.4216

25

0.0078

0.3448

0.3654

0.4577

0.3491

0.3573

0.3168

50

0.0023

0.3268

0.3433

0.3487

0.3228

0.3296

0.2746

100

0.0055

0.3230

0.3229

0.2768

0.3258

0.3271

0.2530

150

0.0065

0.3100

0.3224

0.2542

0.3174

0.3185

0.2508

200

0.0034

0.3117

0.3252

0.2326

0.3125

0.3136

0.2456

10

MREs

0.0004

0.0838

0.0864

0.1270

0.0843

0.0888

0.0843

25

0.0016

0.0690

0.0731

0.0915

0.0698

0.0715

0.0634

50

0.0005

0.0654

0.0687

0.0697

0.0646

0.0659

0.0549

100

0.0011

0.0646

0.0646

0.0554

0.0652

0.0654

0.0506

150

0.0013

0.0620

0.0645

0.0508

0.0635

0.0637

0.0502

200

0.0007

0.0623

0.0650

0.0465

0.0625

0.0627

0.0491

10

MSEs

1.2552

1.7171

1.6830

1.9589

1.6687

1.5782

1.5649

25

0.5255

0.7323

0.6971

0.8212

0.7176

0.6809

0.6329

50

0.2565

0.3988

0.4034

0.4206

0.4080

0.3907

0.3376

100

0.1213

0.2504

0.2401

0.2277

0.2486

0.2397

0.1982

150

0.0823

0.1969

0.1925

0.1614

0.1990

0.1928

0.1522

200

0.0632

0.1707

0.1734

0.1287

0.1757

0.1708

0.1238

The following conclusions are drawn from Tables 2–4.

-

All the considered estimation methods have consistency property, i.e., the MSEs and MREs decrease with the increasing of the sample size .

-

It is observed that the ML method performs better based on the MSEs as compared to other estimation methods.

5 Applications to COVID-19 data

The flexibility of the DMEx distribution is illustrated using two real-life COVID-19 data sets.

The first data refers to the number of COVID-19 daily deaths in China from 23 January to 28 March (https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/country/china/). The observations are listed below in ascending order.

3

3

4

5

5

6

6

7

7

7

8

8

9

10

11

11

13

3

14

15

16

17

22

22

24

26

26

27

28

29

30

31

31

35

38

38

42

43

44

45

46

47

52

57

64

65

71

73

73

86

89

97

97

97

98

105

108

109

114

118

121

136

142

143

146

150

6

18

28

29

44

47

55

116

118

129

150

184

219

236

237

336

421

434

612

648

706

838

1129

1393

1540

1941

2175

2278

2667

2803

2824

n

Min.

Mean

Median

Var

Skewness

Kurtosis

DI

Q3

Max.

Data I

3

49.74

33

1924.8

0.8365

2.4502

38.696

83

150

Data II

6

818.0

336

868739.6

1.0167

2.6308

1062.1

1407

2824

The fitting performance of the DMEx distribution is compared with the following discrete distributions:

-

Discrete Burr (DBurr) distribution. Its PMF is

-

Discrete Burr-Hatke (DBH) distribution. Its PMF is

-

Discrete Rayleigh (DR) distribution. Its PMF is

-

Discrete inverted Topp-Leon (DITL) distribution. Its PMF is

-

Discrete Pareto (DPr) distribution. Its PMF is

-

Discrete inverse Rayleigh (DIR) distribution. Its PMF is

-

Poisson distribution. Its PMF is

The R package called “fitdistrplus” is used to obtain the results in this section. The parameters of the four distributions are estimated using the ML approach. For model comparison, we have considered the log-likelihood (LogL), Akaike’s information criterion (AIC), and Bayesian information criterion (BIC).

The estimates of the parameters and their standard errors (SE) along with goodness of fit measures are presented in Table 6 for both data sets. The values in these tables illustrate that the DMEx provides an adequate fit to the data as compared with other models.

Model

Estimate (SE)

logL

AIC

BIC

Data 1: Number of deaths in China

DMEx

−330.515

663.031

665.220

DBur

−374.500

753.001

757.380

DBH

−461.020

924.039

926.229

DR

−347.227

696.455

698.644

DITL

−366.907

735.815

738.005

DPr

−379.070

760.140

762.330

DIR

−376.380

754.760

756.950

Poisson

−1409.78

2821.57

2823.75

Data 2: Number of deaths in Europe

DMEx

−257.122

516.243

517.677

DBur

−62.902

529.804

532.672

DBH

−56.308

714.616

716.050

DR

−72.816

547.634

549.068

DITL

−59.617

521.234

522.668

DPr

−63.363

528.727

530.161

DIR

−26.987

655.975

657.409

Poisson

−5361.1

30724.2

30725.7

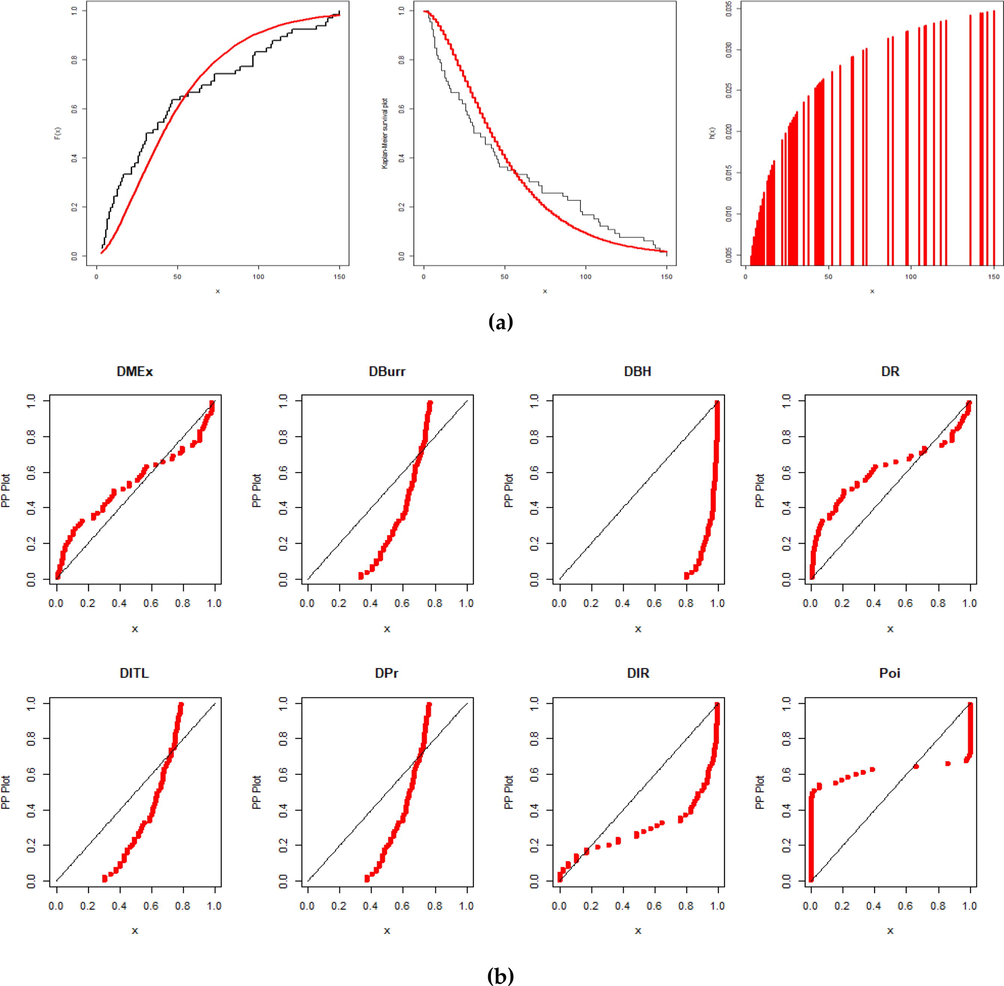

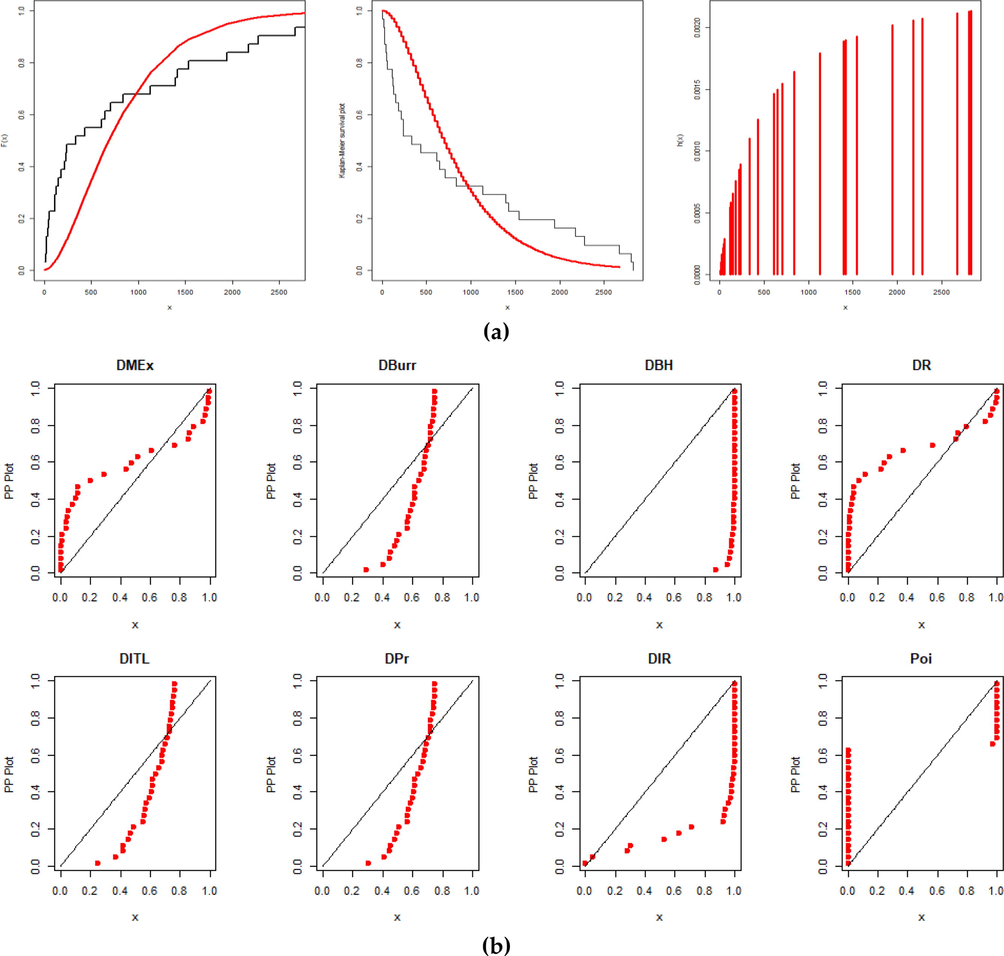

Furthermore, the estimated CDF, SF, and HRF of the DMEx distribution are depicted in Figs. 3(a) and 4(a) for number of deaths in China and Europe, respectively. The probability–probability (P-P) plots of the fitted discrete distributions are displayed in Fisg. 3(b) and 4(b) for the two datasets, respectively.

(a) The fitted CDF, SF, and HRF plots of the DMEx model and (b) the P-P plots of the DMEx model and its competing discrete distributions for number of deaths in China.

(a) The fitted CDF, SF, and HRF plots of the DMEx model and (b) the P-P plots of the DMEx model and its competing discrete distributions for number of deaths in Europe.

In the two applications, we can indicate that the best model representing the daily deaths by COVID-19 is the DMEx distribution. Based on the fitted model, we can answer some questions such as the probability of having more than deaths per day, whereas a prediction based on the mean to the deaths per day by COVID-19.

6 Conclusion

In this article, a new discrete probability distribution called the discrete moment-exponential (DMEx) distribution is proposed. It can be used as an alternative to some well-known discrete distributions. Its mathematical properties of the DMEx distribution are presented. The model parameters are estimated using seven different estimation methods. Comprehensive simulation results are carried out to compare these methods. Based on our study, the maximum likelihood is recommended to estimate the DMEx parameter. The usefulness of the DMEx distribution is illustrated empirically using two applications to the number of deaths due to COVID-19 in China and Europe. The DMEx distribution is quite competitive to the discrete Burr, discrete Burr-Hatke, discrete Rayleigh, discrete inverted Topp-Leon, discrete-Pareto, discrete inverse-Rayleigh, and Poisson distributions. We hope that the DMEx distribution can be applied to traumatic brain injury data following the paper of Ramos et al. (2019).

Acknowledgement

This study was funded by Taif University Researchers Supporting Project number (TURSP-2020/279), Taif University, Taif, Saudi Arabia.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- A new skewed discrete model: properties, inference, and applications. Pakistan J. Stat. Oper. Res.. 2021;17:799-816.

- [Google Scholar]

- A new discrete analog of the continuous Lindley distribution, with reliability applications. Entropy. 2020;22:603.

- [Google Scholar]

- The discrete power-Ailamujia distribution: properties, inference, and applications. AIMS Math.. 2022;7:8344-8360.

- [Google Scholar]

- The uniform Poisson-Ailamujia distribution: actuarial measures and applications in biological science. Symmetry. 2021;13:1258.

- [Google Scholar]

- Asymptotic theory of certain“ goodness of fit” criteria based on stochastic processes. Ann. Math. Stat.. 1952;23:193-212.

- [Google Scholar]

- Binomial-exponential 2 distribution: different estimation methods with weather applications. TEMA (São Carlos). 2017;2017(18):233-251.

- [Google Scholar]

- Generating discrete analogues of continuous probability distributions- a survey of methods and constructions. J. Stat. Distrib. Appl.. 2015;2:1-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Recent advances in Moment distribution and their hazard rates. Lap Lambert academic Publishing GmbH KG; 2012.

- A discrete analog of inverted Topp-Leone distribution: properties, estimation and applications. Int. J. Anal. Appl.. 2021;19:695-708.

- [Google Scholar]

- The discrete Lindley distribution: properties and application. J. Stat. Comput. Simul.. 2011;81:1405-1416.

- [Google Scholar]

- A two parameter discrete Lindley distribution. Revista Colom.Estadistica. 2016;39:45-61.

- [Google Scholar]

- A discrete inverse Weibull distribution and estimation of its parameters. Stat. Methodol.. 2010;7:121-132.

- [Google Scholar]

- A graphical estimation of mixed Weibull parameters in life testing electron tube. Technometrics. 1959;1:389-407.

- [Google Scholar]

- A classes of discrete lifetime distributions. Commun. Stat. Theory Methods. 2004;33(12):3069-3093.

- [Google Scholar]

- Discrete Burr and discrete Pareto distributions. Stat. Methodol.. 2009;6(2):177-188.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comment on “an estimation procedure for mixtures of distributions” by Choi and Bulgren. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Methodol.. 1971;33:326-329.

- [Google Scholar]

- Discrete generalized exponential distribution of a second type. Statistics. 2013;47:876-887.

- [Google Scholar]

- A Discrete analogue of the continuous Marshall-Olkin Weibull distribution with application to count data. Earthline J. Math. Sci.. 2020;5:415-428.

- [Google Scholar]

- Modeling traumatic brain injury lifetime data: improved estimators for the generalized gamma distribution under small samples. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(8):e0221332.

- [Google Scholar]

- Poisson–exponential distribution: different methods of estimation. J. Appl. Stat.. 2018;45(1):128-144.

- [Google Scholar]