Translate this page into:

A comparative study on phytochemical screening, quantification of phenolic contents and antioxidant properties of different solvent extracts from various parts of Pistacia lentiscus L

⁎Corresponding author. med.barbouchi08@gmail.com (Mohammed Barbouchi)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Within the framework of discovering new antioxidants from natural sources, this work focus on screening of phytochemical constituents, the variation in the total phenolic content and the antioxidant capacities from different parts (fruits, twigs and leaves) of Pistacia lentiscus L., from two different regions of Morocco; Moulay Idriss Zerhoun (MIZ) and Melloussa (MLS) was studied. Thirty extracts were prepared from fruits, twigs, and leaves using solvents of different polarity (hexane, ethyl acetate, methanol, ethanol and water). The tests of antioxidant activities were assessed by employing two different assays the 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) and phosphomolybdenum (TAC). The screening tests showed the existence of tannins, flavonoids, saponins, sterols, triterpenes, oses, holosides, reducing sugars and mucilages. The quantitative analysis has proved that the whole plant contains a high amount of total phenolic, this wealth increases as and when the polarity of extraction solvents used increases. The whole plant served as a great source of naturally occurring antioxidants, this study provides that the aqueous extract of Pistacia lentiscus (leaves and twigs) from MIZ is a great natural antioxidant compared to quercetin standard. The results show a very significant positive correlation between the TAC and DPPH assays in relation to the amount of total phenolic.

Keywords

Pistacia lentiscus

Phytochemical screening

Phenolic content

Antioxidant activities

1 Introduction

Currently, the focus of research has been placed on searching new natural antioxidants, in particular of plant origin, has steadily increased. Plants have been an inexhaustible source of medicines and recently, a lot emphasis has been made to find new therapeutic agents based on medicinal plants. Today, a folk favor to use medicinal plants rather than chemical drugs (Dehpour et al., 2009). The antioxidants have high importance in terms of its reducing power of oxidative stress which is one of the causes that could damage biological molecules (Farhat et al., 2013). Pistacia Lentiscus has been known for a long time in traditional medicine for the treatment of various types of diseases. The important has been medically placed grace of its various parts that contain a diversity of chemical constituents.

The purpose of this work was to perform phytochemical screening and to determine the correlation between total phenolic contents and antioxidant activities performed by TAC assay and DPPH assay of different solvent extracts from fruits, twigs and leaves of Pistacia lentiscus L., collected in two different regions of Morocco in order to discover new natural antioxidants.

2 Material and methods

2.1 Plant material

Pistacia lentiscus L. (leaves, twigs and fruits) were collected from two different regions of Morocco: Moulay Idriss Zerhoun (MIZ) Region: Fez-Meknes and Melloussa (MLS) Region: Tangier-Tetouan-AlHoceima, in October 2016. The Geographical coordinates of Moulay Idriss Zerhoun: N 33° 50′ 50,4636″; W 5° 19′ 0,3972″ and Melloussa N 35° 43′ 16,4676″; W 5° 39′ 30,9024″.

The fruits, twigs and leaves of P. lentiscus were air-dried for 15 days at room temperature and then was powdered separately and stored prior to further use.

2.2 Phytochemical screening of plant material

The phytochemical constituents of various parts (leaves, twigs and fruits) of P. lentiscus, were determined by different qualitative tests such as Alkaloid, Tannins, Anthraquinones, Flavonoids, Saponins, Sterols and Triterpenes, Oses and Holosides, Mucilages, Coumarins and Reducing Sugars. The tests were performed by the methods described below: (Diallo, 2005; Abdullahi et al., 2013; Joshi et al., 2013).

2.3 Extraction of crude extracts from different Pistacia lentiscus parts

The different extraction methods were followed to prepare crude extracts from leaves, twigs and fruits of Pistacia lentiscus L., from Melloussa and Moulay Idriss Zerhoun, by various solvents (hexane, ethyl acetate, methanol, ethanol and water).

2.3.1 Infusion

For the aqueous extracts, powdered of the leaves, twigs and fruits of Pistacia lentiscus L., 20 g for each plant parts was extracted with boiling water (200 mL) for 6 h. The aqueous extracts were filtered and evaporated.

2.3.2 Soxhlet extraction

Soxhlet equipment was used in this work. Powdered plant material (25 g) was extracted with solvents of different polarity (hexane, ethyl acetate, methanol and ethanol) for 6 h in about (300 mL). The crude extract of each parts from Pistacia lentiscus was filtered and evaporated.

2.3.3 Extraction yield

with

m1 = mass (g) of different parts (leaves, twigs and fruits) of Pistacia lentiscus starting.

m2 = mass (g) of crude extracts.

2.4 Instrumentation

All spectrophotometric data were acquired using SHIMADZU UVmin-1240 UV-VIS spectrophotometer. Glass cuvettes (1 cm × 1 cm × 4.5 cm).

2.5 Determination of total phenolic content (TPC)

Total phenolic content in the Pistacia lentiscus extracts was determined to use the Folin-Ciocalteu method as described by Singleton et al. (1999). Briefly, 0.3 ml of the crude extract (1 mg/ml) was added to 1.5 ml Folin-Ciocalteu reagent (10/100). The mixing was incubated for six min and mixed with 1.2 ml of Na2SO4 (7.5%). The prepared samples were incubated in darkness for two hours, the absorbance made at 760 nm. Total phenolics were expressed as Gallic acid equivalents (GAE) in mg/g of crude extract. The data were presented on average ± SD for the triplicates. The content of the total phenolic was calculated using the linear equation from the calibration curve: where A is the absorbance and X in mg/g (presented total phenolic content).

2.6 Antioxidant activities

2.6.1 Determination of the free radical scavenging activity (DPPH)

The power of plant extracts to scavenge DPPH free radicals was specified according to the method described by Brand-Williams et al. (1995). Briefly, 0.05 ml of the crude extracts were mixed with 1.95 ml freshly prepared DPPH solution in a concentration of 24 mg in 100 ml ethanol. After 1/2 h of the incubation of samples in darkness, the measured absorbance was made at 515 nm, with a positive control (Ascorbic acid). The percentages of inhibition of the DPPH free radical, as a function of the extracts concentrations, were determined to use the equation:

The antioxidant capacity has been determined from the IC50 value, which is the Concentration of the antioxidant that is needed to trap 50% of DPPH in the test solution. The efficient concentration EC50 was expressed in terms of the concentration of sample extract used for the test (mg/ml) and the quantity of extract in relation to the quantity of initial DPPH (mg/mg DPPH).

The higher the antioxidant capacity, the lower the effective concentration. For rational reasons of clarity, the antiradical power ARP was determined as the reciprocal value of the efficient concentration EC50. (Kroyer, 2004).

2.6.2 Determination of total antioxidant capacity (TAC)

Total antioxidant capacity in the P. lentiscus L. extracts was determined to use the phosphomolybdenum method as described by Prieto et al. (1999). Each sample (0.6 ml) is mixed with 6 ml reagent solution (sodium phosphate (28 mM), sulfuric acid (0.6 M) and ammonium molybdate (4 mM)). The tubes incubated for 90 min at 95 °C. After cooling, the absorbance made at 695 nm against the white which (6 ml reagent solution is mixed with 0.6 ml of methanol) and is incubated within the same basic conditions as the samples. The ascorbic acid (AA) was used as standard and the TAC assay is presented in milligram equivalents of ascorbic acid per gram of crude extract (mg EAA/g of crude extract).

2.7 Statistical analyses

All tests were conducted in triplicates and the data were presented on an average ± SD. The result was statistically analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Duncan's. Average values were considered statistically significant when P < 0.05. The correlation between the contents of total phenolic and antioxidant activities was determined as Pearson's correlation coefficient, the difference is considered statistically significant when P < 0.05.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Phytochemical screening

The phytochemical screening of various parts (leaves, twigs, and fruits) of Pistacia lentiscus L., showed the great presence of tannins, flavonoids, saponins, sterols, triterpenes, oses, holosides, reducing sugars and mucilages. While antraquinones free and anthraquinons combined were absent. Although, the alkaloids present in fruits and absent in the leaves and twigs (See Table 1). High concentration (+++); moderate concentration (++); low concentration (+); absence (----).

Phytoconstituent

Test

Pistacia lentiscus (MIZ)

Pistacia lentiscus (MLS)

Twigs

Leaves

Fruits

Twigs

Leaves

Fruits

Alkaloides

Dragendorff’s Mayer’s

----

--------

----++

++----

--------

----++

++

Tannins Catechics

Stiansy reaction

+++

+++

+++

+++

+++

+++

Tannins Gallics

Lead acetate

+++

+++

+++

+++

+++

+++

Anthraquinons Free

Borntrager’s

----

----

----

----

----

----

Anthraquinons combined

O-heterosides

Reduced GeninsModified Borntrager’s

----

----

----

----

----

---

C-heterosides

----

----

----

----

----

----

Flavonoids

Shinoda’s

+++

+++

+++

+++

+++

+++

Saponins

Foam Index: positive if >100

+++

200+++

125++

100+++

200++

100+++

125

Sterols and Triterpenes

Liberman-burchard

+++

+++

+++

+++

+++

+++

Oses and holosides

Saturated alcohol with thymol

+++

+++

+++

+++

+++

+++

Mucilages

Alcohol 95%

++

++

++

++

++

++

Reducing sugars

Fehling’s

+++

+++

++

+++

+++

++

3.2 Extraction yields of Pistacia lentiscus L

It is apparent through observing the extraction yields presented in Table 2, they differ significantly (p < 0.05) on the one hand, according to the plant parts, on the other hand, the solvent used. Methanol gives the best extraction yield an average of 37.344% on three samples (leaves, fruits, and twigs) of P. lentiscus from two regions, while hexane gave the lowest yield (15.177% on average). As for the plant parts usually, regardless of the extraction solvent, the extract fruits recorded the highest yields.

Yields%

Water

Ethanol

Methanol

Ethyl acetate

Hexane

Pistacia lentiscus from MIZ

Twigs

12,47 ± 0,08d

13,94 ± 0,03f

21,93 ± 0,011c

5,45 ± 0,00d

3,20 ± 0,00d

Leaves

27,80 ± 0,14a

26,70 ± 0,13d

51,33 ± 0,89a

12,00 ± 0,01c

6,32 ± 0,03c

Fruits

21,31 ± 0,14c

43,18 ± 0,09a

51,60 ± 1,07a

42,03 ± 0,69a

48,16 ± 0,61a

Pistacia lentiscus from MLS

Twigs

7,14 ± 0,04e

16,31 ± 0,02a

20,03 ± 0,02c

6,50 ± 0,00d

4,54 ± 0,01d

Leaves

24,69 ± 0,09b

38,33 ± 0,02b

39,67 ± 0,44b

13,62 ± 0,03b

7,71 ± 0,01c

Fruits

25,04 ± 0,12b

36,25 ± 0,13c

39,50 ± 0,33b

13,12 ± 0,02b

21,13 ± 0,03b

Means Yields%

19,74

29,19

37,34

15,62

15,18

3.3 Total phenolic content (TPC)

The results of the TPC in all 30 studied extracts of various parts of Pistacia lentiscus L. by different solvents (Table 3) show a significant difference (p < 0.05) between the concentration of total phenolic. The great distinction between the plant parts appears due to the wealth of some and the poverty of others could be assigned to extraction solvents used, different environmental and climatic conditions (Özcan et al., 2009; Özcan, 2004; Couladis et al., 2003).

Bioactive compounds

TPC (mg GAE/g)

TAC (mg AA/g)

DPPH radical scavenging

IC50 (mg/mL)

EC50 (mg/mgDPPH)

ARP

Aqueous extract

PL from MIZ

Twigs

302,01 ± 1,12b

453,22 ± 0,66b

0,09 ± 0,00

3,89 ± 0,01

25,76 ± 0,05b

Leaves

345,95 ± 1,17a

488,16 ± 0,82a

0,09 ± 0,00

3,83 ± 0,02

26,12 ± 0,12a

Fruits

192,68 ± 3,68h

298,53 ± 1,15g

0,23 ± 0,00

9,75 ± 0,04

10,26 ± 0,04h

PL from MLS

Twigs

167,63 ± 0,76k

409,02 ± 0,41c

0,10 ± 0,00

4,17 ± 0,02

23,98 ± 0,1c

Leaves

299,68 ± 1,12b

269,52 ± 1,23k

0,50 ± 0,00

21,03 ± 0,07

4,76 ± 0,02l

Fruits

160,83 ± 0,67l

258,28 ± 1,15n

0,53 ± 0,00

22,06 ± 0,00

4,53 ± 0,00 m

Ethanolic extract

PL from MIZ

Twigs

232,95 ± 0,94e

319,27 ± 0,91f

0,18 ± 0,00

7,32 ± 0,02

13,66 ± 0,04f

Leaves

255,85 ± 0,90c

352,76 ± 1,15d

0,13 ± 0,00

5,27 ± 0,02

18,99 ± 0,07d

Fruits

125,61 ± 0,45p

217,91 ± 0,41s

1,45 ± 0,01

60,44 ± 0,4

1,66 ± 0,01s

PL from MIZ

Twigs

147,90 ± 0,94mn

246,31 ± 0,66p

0,66 ± 0,00

27,54 ± 0,08

3,63 ± 0,01o

Leaves

243,90 ± 0,85d

349,40 ± 0,58e

0,17 ± 0,00

7,03 ± 0,01

14,22 ± 0,01e

Fruits

127,02 ± 0,72p

211,74 ± 0,25t

1,55 ± 0,00

64,51 ± 0,07

1,55 ± 0,01 t

Methanolic extract

PL from MIZ

Twigs

226,42 ± 0,85f

297,05 ± 0,91h

0,22 ± 0,00

9,28 ± 0,09

10,78 ± 0,1g

Leaves

146,08 ± 0,67n

239,89 ± 0,25q

1,13 ± 0,00

47,28 ± 0,02

2,12 ± 0,00p

Fruits

110,79 ± 0,63r

207,91 ± 0,66u

1,61 ± 0,01

67,08 ± 0,55

1,49 ± 0,01t

PL from MLS

Twigs

202,11 ± 0,85g

292,85 ± 0,49i

0,24 ± 0,00

10,02 ± 0,01

9,94 ± 0,01i

Leaves

150,12 ± 0,81 m

254,58 ± 0,58o

0,57 ± 0,00

23,66 ± 0,08

4,23 ± 0,01n

Fruits

120,69 ± 0,49q

221,74 ± 0,25r

1,35 ± 0,01

56,11 ± 0,36

1,78 ± 0,01r

Ethyl acetate extract

PL from MIZ

Twigs

134,43 ± 0,72o

221,86 ± 0,58r

1,21 ± 0,01

50,59 ± 0,21

1,98 ± 0,01q

Leaves

168,71 ± 0,67k

261,74 ± 0,25m

0,54 ± 0,00

22,31 ± 0,15

4,48 ± 0,03m

Fruits

85,95 ± 0,45t

189,90 ± 0,41w

2,29 ± 0,03

95,25 ± 1,4

1,05 ± 0,02u

PL from MLS

Twigs

175,44 ± 2,92j

266,19 ± 0,25l

0,49 ± 0,00

20,32 ± 0,15

4,92 ± 0,04k

Leaves

186,75 ± 0,72i

277,42 ± 0,41j

0,44 ± 0,00

18,24 ± 0,03

5,48 ± 0,01j

Fruits

105,14 ± 0,76s

201,37 ± 0,49v

1,58 ± 0,02

66,02 ± 0,83

1,52 ± 0,02t

Hexane extract

PL from MIZ

Twigs

48,71 ± 0,27wx

100,26 ± 0,49aa

35,02 ± 0,05

50,59 ± 0,21

1,98 ± 0,01q

Leaves

75,71 ± 0,31u

164,70 ± 0,25x

3,00 ± 0,01

22,31 ± 0,15

4,48 ± 0,03m

Fruits

36,45 ± 0,45y

96,56 ± 0,49ab

93,98 ± 0,34

95,25 ± 1,4

1,05 ± 0,02u

PL from MLS

Twigs

49,58 ± 0,22w

123,10 ± 0,41z

22,82 ± 0,06

20,32 ± 0,15

4,92 ± 0,04k

Leaves

67,83 ± 0,36v

153,10 ± 0,41y

3,00 ± 0,01

18,24 ± 0,03

5,48 ± 0,01j

Fruits

46,82 ± 0,36x

62,48 ± 0,25ac

93,21 ± 0,36

66,02 ± 0,83

1,52 ± 0,02t

Standard Quercetin

0,10 ± 0,00

0,04 ± 0,00

24,03 ± 0,05c

The results revealed that the Pistacia lentiscus leaves are very rich in phenolic compounds (varied from 345,95 ± 1,17 to 67,83 ± 0,36 mg of GAE/g of extract), followed by twigs (varied from 302,01 ± 1,12 to 48,71 ± 0,27 mg of GAE/g of extract) and the fruits (ranged between 192,68 ± 3,68 to 36,45 ± 0,45 mg of GAE/g of extract). The ethanol and water were great solvents than the others in extracting phenolic compounds from the extracts owing to their good solubilities and polarities, followed by methanol and the lower polarity solvents, particularly: ethyl acetate and hexane showed the lower capacity in extracting the phenolic compounds.

It can, therefore, be concluded that higher polar solvents were more effective at extracting phenolic compounds from all parts of the plant than less polar solvents (Galanakis et al., 2013).

There are several studies have confirmed that the Pistacia lentiscus L. plant is rich in phenolic compounds, this wealth increases as and when the polarity of extraction solvents used increases (Bampouli et al., 2014; Botsaris et al., 2015; Zitouni et al. 2016).

3.4 Antioxidant activities of the extracts of Pistacia lentiscus

3.4.1 Total antioxidant capacity (TAC)

The TAC obtained by the phosphomolybdenum method is expressed as (mg EAA/g of crude extract). The results for TAC are presented in Table 3, show a significant difference (p < 0.05) in the TAC of all extracts of Pistacia lentiscus. The Aqueous extract of Pistacia lentiscus leaves from MIZ, showed the highest TAC with 488,16 ± 0,82 mg AA/g of extract. One clearly sees that ethanolic and aqueous extracts of Pistacia lentiscus (leaves and twigs) are recording the greatest TAC, while the hexane extract of Pistacia lentiscus fruits from MLS had the least amount of TAC with 62,48 ± 0,25 mg AA/g.

3.4.2 DPPH free radical scavenging

The antioxidant activity of all extracts of Pistacia lentiscus is assessed by the free radical DPPH reduction method. The results obtaining as given in Table 3. From these results, the greatest antioxidant activity was found in aqueous extracts of Pistacia lentiscus (leaves and twigs) from MIZ, who is stronger than the quercetin standard with a significant difference (p < 0.05). However, there was no statistically significant difference observed between the quercetin standard and the aqueous extracts of Pistacia lentiscus twigs from MLS, while no remarkable antioxidant capacity was found in the hexane extracts of various parts of Pistacia lentiscus from MLS and MIZ.

3.5 Correlation

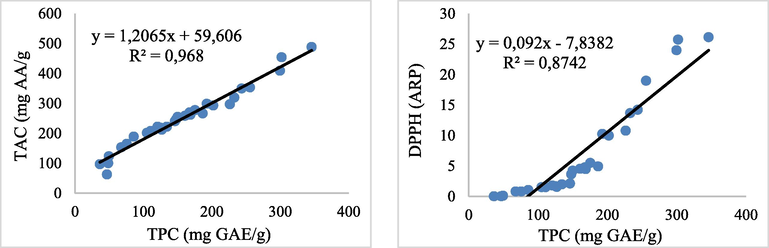

The dependency of antioxidant activity obtained through each assay, in relationship to the TPC, was also evaluated. The results show a very significant positive correlation in the cases of DPPH scavenging activity (R2 = 0,8742) and TAC (R2 = 0,968), in relationship to the content of phenols.

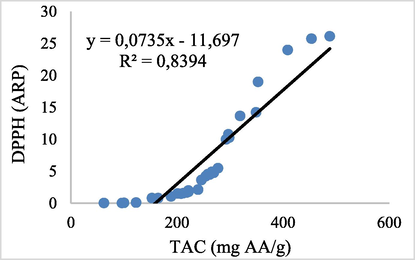

Although, there is a positive linear correlation among the antioxidant activities assessed by DPPH assay and TAC assay for R2 = 0,839. The results indicated that the phenolic compounds in the different Pistacia lentiscus parts could be the main contributor to the antioxidant activities. This result was in similarity with many previous studies (Botsaris et al., 2015; Zitouni et al., 2016) Figs. 1 and 2.

Linear regression between TPC and the antioxidant activities by TAC assay and DPPH assay.

Linear regression between the antioxidant activities by TAC assay and DPPH assay.

4 Conclusions

In this work, we have opted for the study of the phytochemical screening and to determine the TPC and the antioxidant activities by DPPH and TAC assays from the leaves, twigs and fruits of Pistacia Lentiscus L., collected from two different regions of Morocco. The present work proved that the use of different solvents polar in extraction had a big influence significantly (p < 0.05) on the total phenolic contents, total antioxidant capacity and antioxidant activity of obtained extracts, as well as the richness of Pistacia lentiscus L. in secondary metabolites and in phenolic contents. These results showed that the aqueous extracts of P. Lentiscus (leaves) had the highest contents of a phenolic compound and the greatest antioxidant activity in the DPPH and TAC assays. The results indicated that the different part of Pistacia lentiscus L. could be a potential natural source of antioxidants and may have greater importance as a natural antioxidant able to slow down or prevent oxidative stress.

References

- Evaluation of phytochemical screening and analgesic activity of aqueous extract of the leaves of Microtrichia perotitii Dc (Asteraceae) in mice using hotplate method. Med. Plant. Res.. 2013;3:37643.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of different extraction methods of Pistacia lentiscus var. chia leaves: yield, antioxidant activity and essential oil chemical composition. J. Appl. Res. Med. Aromat. Plants.. 2014;1:81-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antioxidant and antimicrobial effects of Pistacia lentiscus L. extracts in pork sausages. Food Technol. Biotechnol.. 2015;53:472-478.

- [Google Scholar]

- Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. Food. Sci. Technol.. 1995;28:25-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparative essential oil composition of various parts of the turpentine tree (Pistacia terebinthus L) growing wild in Turkey. J. Sci. Food Agric.. 2003;83:136-138.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antioxidant activity of the methanol extract of Ferula assafoetida and its essential oil composition. Grasas Y Aceites.. 2009;60:405-412.

- [Google Scholar]

- Etude de la phytochimie et des activités biologique de Syzygium guineense. willd. (myrtaceae). Mali: PhD. of the University Bamako; 2005. p. :38-47.

- Characterization and quantification of phenolic compounds and antioxidant properties of Salvia species growing in different habitats. Ind. Crops. Prod.. 2013;49:904-914.

- [Google Scholar]

- A knowledge base for the recovery of natural phenols with different solvents. Int. J. Food. Prop.. 2013;16:382-396.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phytochemical investigation of the roots of Grewia microcos Linn. J. Chem. Pharm. Res.. 2013;5:80-87.

- [Google Scholar]

- Red clover extract as antioxidant active and functional food ingredient. Innov. Food. Sci. Emerg. Technol.. 2004;5:101-105.

- [Google Scholar]

- Characteristics of fruit and oil of terebinth (Pistacia terebinthus L) growing wild in Turkey. J. Sci. Food Agric.. 2004;84:517-520.

- [Google Scholar]

- Essential oil composition of the turpentine tree (Pistacia terebinthus L.) fruits growing wild in Turkey. Food Chem.. 2009;114:282-285.

- [Google Scholar]

- Spectrophotometric quantitation of antioxidant capacity through the formation of a phosphomolybdenum complex: specific application to the determination of vitamin E. Anal. Biochem.. 1999;269:337-341.

- [Google Scholar]

- Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of folin-ciocalteu reagent. Methods Enzymol.. 1999;299:152-178.

- [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of phytochemical composition and antioxidant properties of extracts from the leaf, stem, fruit and root of Pistacia lentiscus L. Int. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. Res.. 2016;8:627-633.

- [Google Scholar]