Translate this page into:

Investigation of microstructural and magnetic properties of Ca2+ doped strontium hexaferrite nanoparticles

⁎Corresponding authors. jahmed@ksu.edu.sa (Jahangeer Ahmed), aksoodchem@yahoo.co.in (Ashwani Kumar Sood)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

The effect of Ca2+ ions doping on the structure, magnetic properties, and surface morphology of Sr1-xCaxFe12O19 (x = 0.0 to 0.5 with step size 0.1) hexaferrite nanoparticles synthesized using the sol–gel auto-combustion technique was investigated in the current study. The phase purity of synthesized samples is confirmed by XRD data plots up to x = 0.2, after which α-Fe2O3 was observed as a secondary phase in all concentrations. The micrographs from FESEM show that with the increase in the concentration of Ca2+ dopant, the average grain size increases from ≈125 nm to ≈240 nm. The intensity of secondary phase Raman peaks increases with increasing dopant ion concentration beyond x = 0.2. The coercivity value varies between 5292 and 5828 Oe as the Ca2+ dopant increases. A maximum (72.63 emu/g) value of saturation magnetization (Ms) have been obtained in samples at x = 0.2. Such substances can be utilized for making permanent magnets applications.

Keywords

Sol-gel processes

Strontium hexaferrite

Dielectric properties

Magnetic properties

Hard magnets

1 Introduction

In the field of ferrite-based permanent magnetic materials, the discovery of M-type (Magnetoplumbite) hexaferrite in the 1950s marked a watershed moment (Pullar 2012). Due to their critical role in the fabrication of key components for many different devices and machines, magnetic materials are in high demand in the electronics industry. High coercivity, high magnetic saturation and remanence, high magnetocrystalline anisotropy, excellent chemical stability, and a high Curie temperature have all been associated with M-type hexaferrite (Urbano-Peña et al., 2019). A search for low-cost (Mehtab et al., 2022; Ahmad et al., 2013) and high-performance magnetic material leads to the development of new M-type hexaferrite material. Ca is available in abundance in our earth bulk as compared to their Ba and Sr and hence its metal nitrate and oxides are cheaper than other counterparts Ba (Christy et al., 2019). If calcium hexaferrite (CaM) could be synthesized in phase pure form, it would be a low-cost substitute for Ba/Sr - based hexaferrite. Hexaferrites contain one large divalent metal ion (M2+=Ba/Sr/Pb/Ca), which disrupts the crystal lattice due to size differences, resulting in high magnetocrystalline anisotropy. Lotgering (Lotgering and Huyberts 1980) described lanthanum ferrite as a material with large magnetocrystalline anisotropy. Ca is least studied as a dopant in M-type hexaferrites. Ca-doped hexaferrites have been shown to improve coercivity, increase the reaction rate, lower phase formation temperature, and thus control grain size more easily (Chauhan et al., 2018; Sable et al., 2010; Ali et al., 2013). As a result, it is worthwhile to investigate the magnetic properties of MFe12O19 by replacing M2+ with Ca2+. The current study reports on the synthesis of Sr1-xCaxFe12O19 (x = 0.0 to 0.5) hexaferrite nanoparticles over a wide concentration range. The magnetic, morphological, and structural characteristics of the prepared samples were studied in depth.

2 Experimental

To synthesize Ca2+-doped strontium hexaferrite nanoparticles (by sol–gel auto-combustion method), calcium nitrate, ferric nitrate, strontium nitrate, and citric acid (all the chemicals were AR grade having purity >98%) were used as such without further purification. Double distilled water was used to dissolve metal nitrate salts in the required stoichiometric ratio (as listed in Table 1). Afterward, the citric acid was mixed in the above solution on a magnetic stirrer at room temperature. Ammonia solution (25%) was added drop-wise to maintain a pH of 7. The temperature of the resulting solution was raised to 90–100 °C using a hot plate. With continuous heating for a few hours, the excess water evaporates, leaving a brown gel that looks like honey. The gel was kept in an oven for 1 h at 200 °C to allow auto combustion reactions. Mixed metal oxide precursor material was obtained after the auto-combustion reaction. Impurities were removed from the powder samples using a muffle furnace and calcination for 6 h at 900 °C to convert the amorphous phase to the crystalline phase.

Composiiton

Strontium nitrate (g)

Calcium nitrate (g)

Ferric nitrate (g)

Citric acid (g)

SrFe12O19

2.116

0

48.48

25

Sr0.9Ca0.1Fe12O19

1.904

0.236

48.48

25

Sr0.8Ca0.2Fe12O19

1.693

0.473

48.48

25

Sr0.7Ca0.3Fe12O19

1.480

0.708

48.48

25

Sr0.6Ca0.4Fe12O19

1.269

0.945

48.48

25

Sr0.5Ca0.5Fe12O19

1.058

1.180

48.48

25

The Rigaku Miniflex-II diffractometer (20-80° range of 2θ utilizing Cu-α emission (λ = 1.54 A), 0.005 step size) was used to study the phase purity, and structure of the materials. FESEM (operating voltage 20 kV) from JEOL, JSM-7100, and energy dispersive X-ray (EDX) analysis were carried out for surface morphology and elemental analysis. Confocal Renishaw Raman Spectrophotometer having laser of 514 nm excitation wavelength was used to obtain structural features in 100–800 cm−1 wavenumber range. VSM (vibrating sample magnetometer, Microsense EV-90) was used to make magnetic measurements.

3 Results and discussion

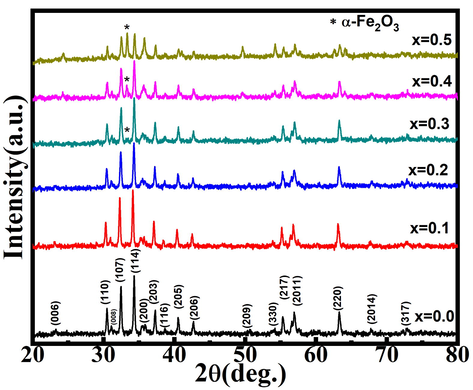

XRD data of the Sr(1-x)CaxFe12O19 (x = 0.0–0.5) materials is shown in Fig. 1. According to international standard diffraction data, the peaks of all six compositions correspond to the M-type strontium hexaferrite phase (Godara et al., 2022). At concentration x ≥ 0.3, additional peaks marked with ‘*’, indicating hematite (α-Fe2O3) secondary phase was observed. The intensity of the 〈1 0 7〉 and 〈1 1 4〉 planes decreases as dopant ion concentration increases, while the intensity of the α-Fe2O3 peak increases. As a result, as the concentration of Ca2+ doping increases, the α-Fe2O3 phase grows at the expense of the M-type phase. This indicates lower calcium solubility in SrM phase at 900 °C. The lower solubility of calcium is due to its smaller ionic radii, which is responsible for the appearance of the hematite phase. The calcium solubility can be improved by increasing calcination temperature and time (Mohammed et al., 2018; Ahmad et al., 2013).

XRD patterns for Sr(1-x)CaxFe12O19 (x = 0.0–0.5).

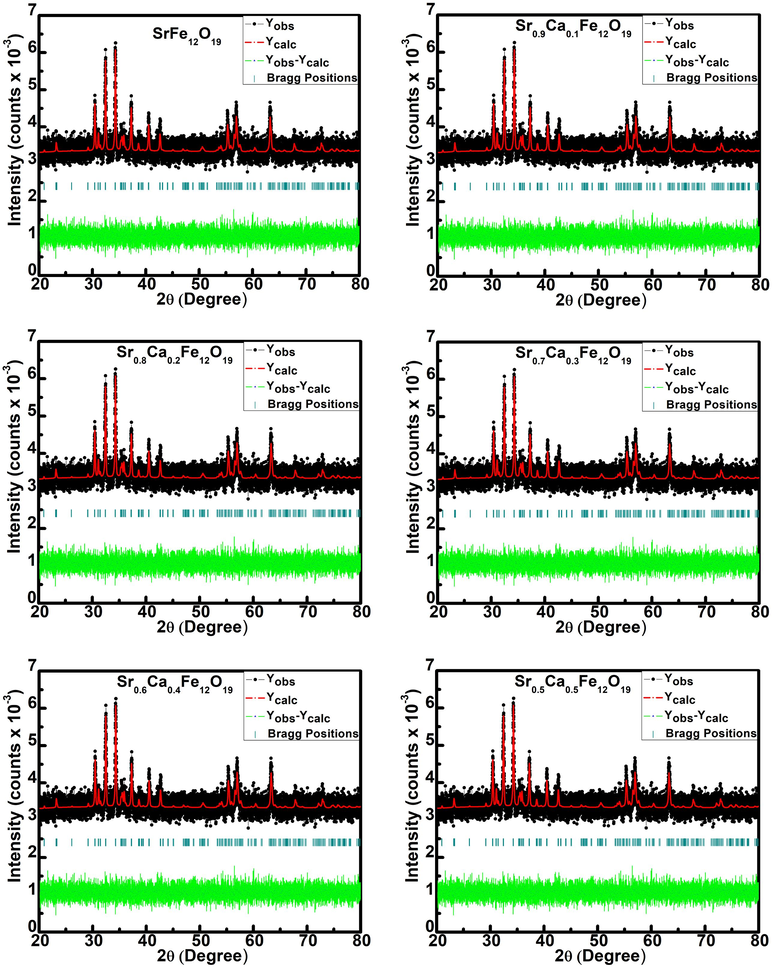

Rietveld refinement was performed by Fullprof software to further establish %age phase purity and determine other structural characteristics. For Rietveld refinement, the basic structure (starting lattice parameters and atomic locations) was assumed the same as in ISCD 98-002-6353. The procedure is also reported elsewhere (Godara et al., 2019). The corrected data matches the experimental data fairly well, and the difference data is randomly distributed around zero, as seen in Fig. 2. The Rietveld refined parameters for x = 0.0–0.5 were tabulated in Table 2.

Rietveld refinement of Sr1-xCaxFe12O19 (x = 0.0–0.5).

Composition (x)

c (Å)

a = b (Å)

V (Å)3

c/a

GoF

M-type Phase %age

Hematite phase %age

0.0

23.0383

5.8759

689.3153

3.920812

7.07

100

absent

0.1

23.0206

5.8751

688.5981

3.918333

6.99

100

absent

0.2

22.2972

5.8689

665.5527

3.799213

7.13

100

absent

0.3

23.0270

5.8757

688.9303

3.919022

7.11

97.64

2.36

0.4

23.0193

5.8760

688.7702

3.917512

6.80

84.01

15.99

0.5

23.0463

5.8756

689.4842

3.922374

6.77

68.91

31.09

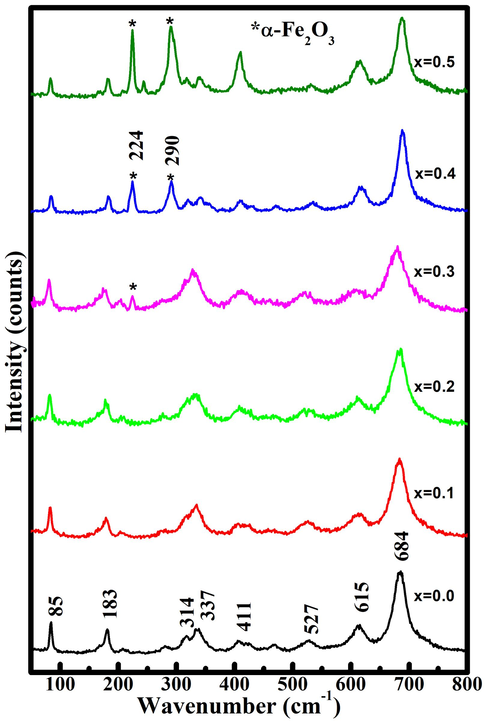

The lattice constants ‘c & a' as well as cell volume decreases with an increase ‘x = 0.2,’ while the lattice constants ‘a & c' as well as cell volume randomly varies for x > 0.2 due to the appearance of the hematite phase. The observed decrease in cell volume and the lattice constants ‘a & c' could be due to the smaller ionic radius of Ca2+ (0.99) (Ubaidullah et al., 2020) compared to Sr2+ ((1.49) Kaur et al., 2017). As a result of the decrease in lattice parameters, it can be concluded that the incorporation of Ca2+ ions into the crystal structure of SrFe12O19 was successful. Verstegen and Stevels have already demonstrated that if the observed c/a ratio is less than 3.98 (Yang et al., 2014), the structure is assumed to be M-type. The observed c/a values in all synthesized samples are less than 3.93, confirming the M-type hexaferrite phase. The presence of secondary phases, bond length, local and dynamic symmetry, local strain, and structural distortion of M-type hexaferrite materials can be investigated using Raman spectroscopy. The Raman spectra of Sr(1-x)CaxFe12O19 (x = 0.0–0.5) are shown in Fig. 3. When compared to the literature (Kaur et al., 2017; Ashima et al., 2012; Alhokbany et al.,2021), our results show that x ≥ 0.3, has two more peaks of α-Fe2O3 secondary phase at 224 and 290 cm−1, in addition to peaks corresponding to SrM phase at 85, 183, 314, 337, 411, 527, 615 and 684 cm−1.

Raman spectra for Sr(1-x)CaxFe12O19 (x = 0.0–0.5).

XRD data also exhibits α-Fe2O3 secondary phase for x ≥ 0.3, suggesting the existence of secondary phase which agrees well with the results obtained from Raman spectroscopy. The sharpness and the intensity of the secondary phase (α-Fe2O3) peaks increase beyond x = 0.2, which reveals that the concentration of α-Fe2O3 continuously increases with calcium doping. Due to E1g symmetry, the mode at 183 matching to the vibrational mode of the entire spinel block were discovered at lower Raman shift (Mohammed et al., 2020, Musa et al., 2021). The vibrational mode observed around 314 and 337 cm−1 occurs due to the O-Fe-O vibrations. The mode around 411 cm−1 transpires may be due to the Fe(12 k)/Ca(12 k)O6 octahedra vibrations whereas, the mode around 527 cm−1 arises due to the Fe(4f2)/Ca(4f2)O6 octahedra vibrations. In addition, the Raman active modes around 615 cm−1 and 684 cm−1 may be occurred due to the vibrations of anion sublattices called as, Fe(2b)/Ca(2b)O5 and Fe(4f1)/Ca(4f1)O4 respectively (Jasrotia et al., 2020).

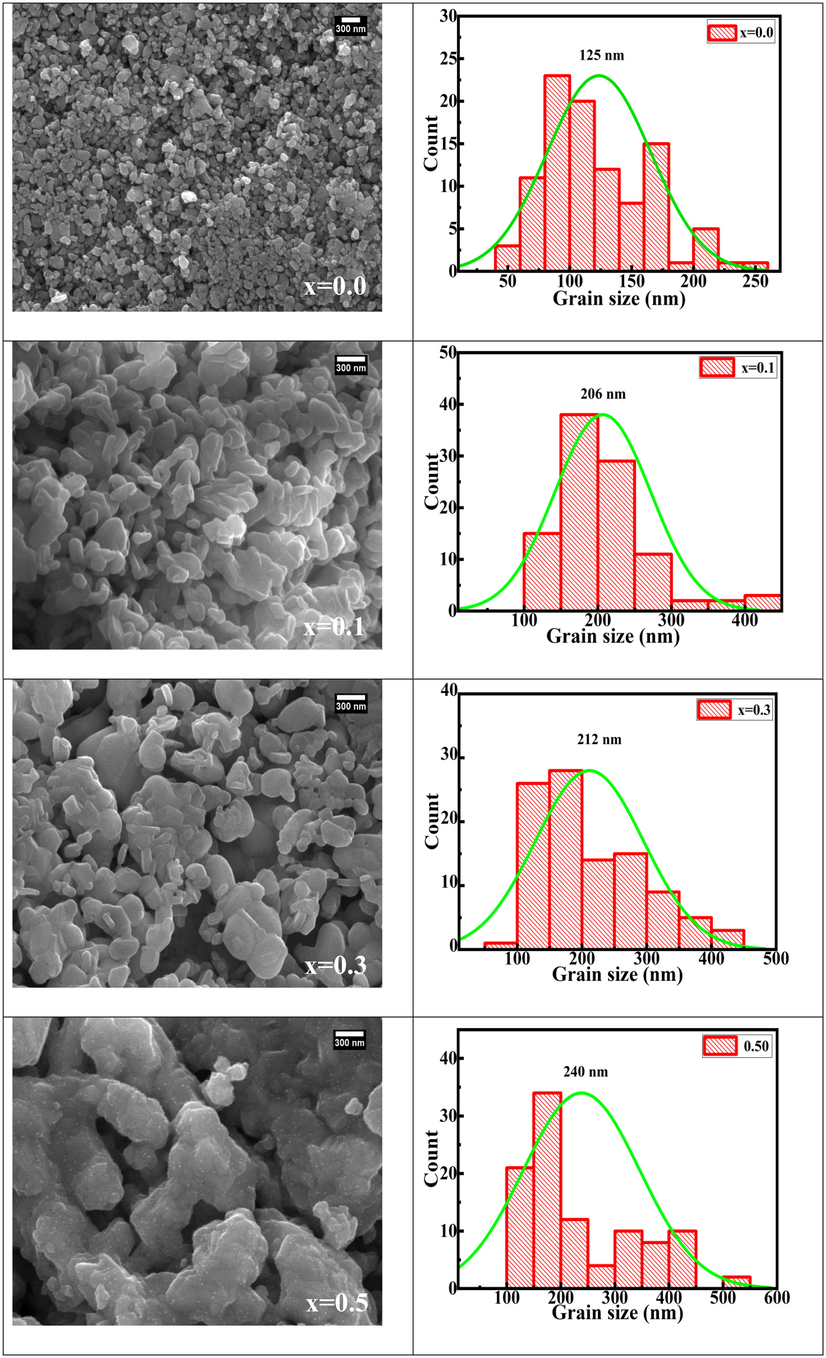

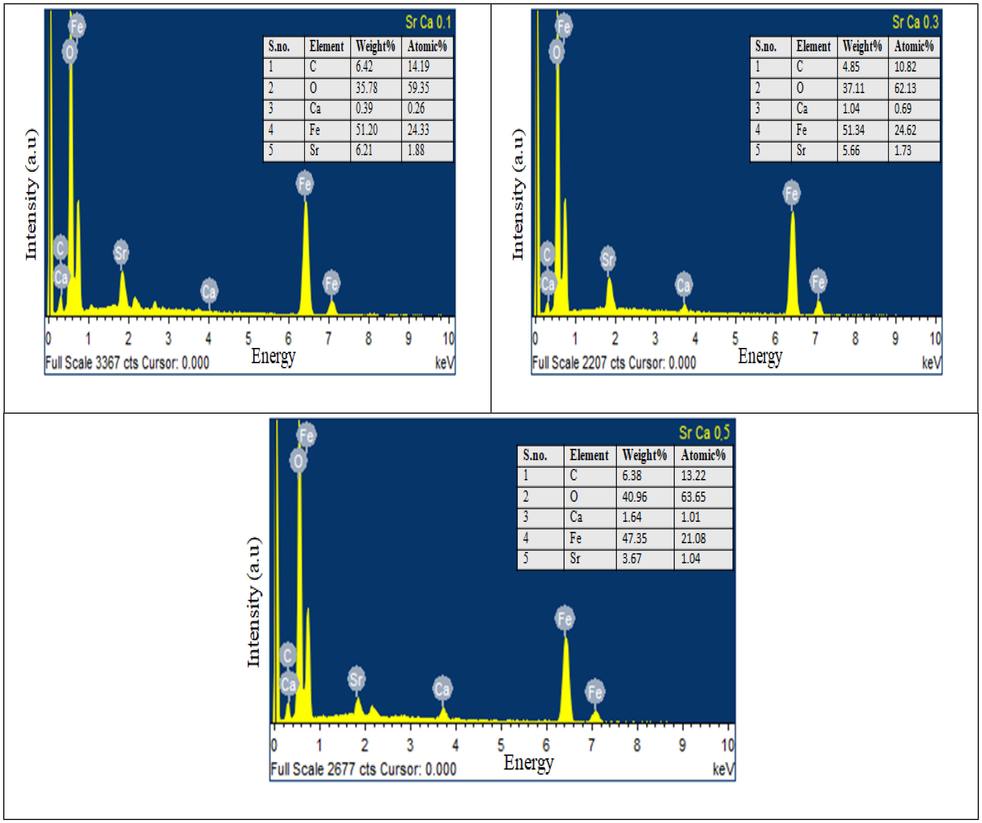

FESEM micrographs of Sr(1-x)CaxFe12O19 (x = 0.0, 0.1,0.3,0.5) are shown in Fig. 4. In FESEM micrographs, particles are highly agglomerated (as a result of magnetic interaction between the individual grains of the samples) [Trudel et al., 2019] and the average particle size continuously increases from 125 nm (x = 0.0) to 240 nm (x = 0.5). Godara et al. also reported similar trends in literature at higher calcination temperature 1200 °C (Godara et al., 2021, Mohammed et al., 2018, Mohammed et al., 2019). The grain size increases upon replacing Sr2+ ion with a smaller radius of Ca2+ ion in samples from x = 0.0 to 0.5. The smaller size of Ca2+ ion facilitates ionic diffusion and thus promotes the growth of grains (Godara et al., 2021; Blanco and Gonzalez, 1989). The small spherical-shaped particles on the surface of agglomerated grains in the significant number were observed only in the x = 0.5 sample, which may be secondary hematite phase present in a considerable amount as also revealed in XRD plots. The elemental data for samples (x = 0.1, 0.3, and 0.5) are tabulated in the inset of EDX spectra in Fig. 5. The EDX spectra show the presence of Ca, Sr, Fe and O atoms. The observed increase in Ca content confirms the successful replacement of Strontium ions by calcium ions in prepared samples.

FESEM micrographs and histograms for Sr(1-x)CaxFe12O19 (x = 0.0, 0.1, 0.3, and 0.5).

EDX spectra of Sr(1-x)CaxFe12O19 (x = 0.1, 0.3, and 0.5).

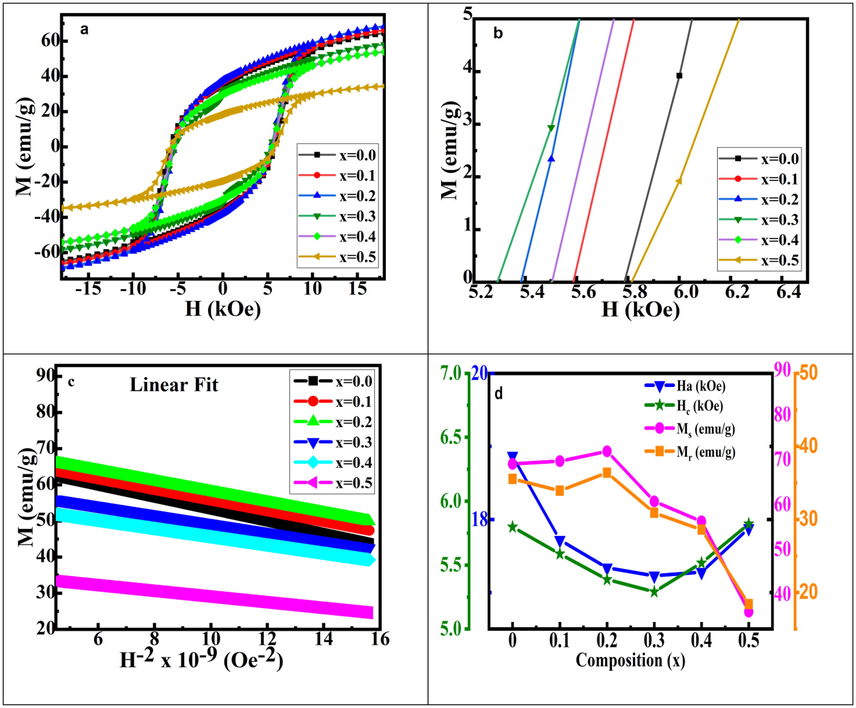

The M-H plots were recorded at room temperature in pellet form for Sr(1-x)CaxFe12O19 (x = 0.0–0.50) is shown in Fig. 6a and 6b. M-H plots revealed the non-saturating behavior of all the synthesized samples in the applied field range. To obtain Ms, saturation law i.e plotting M vs. 1/H2 data, and then a straight line was fitted to it, which was then used in data of M vs. H in the range 8 to 18 kOe (Godara et al., 2021) using equation (3). The fitting plot of a straight line is shown in Fig. 6c.

Magnetic measurement of Sr(1-x)CaxFe12O19 (x = 0.0–0.5) samples: a) M vs. H graphs, b) zoomed view of M vs. H graphs, c) linear fitting of M vs. 1/H2 to determine Ms and d) graphs of Ha, Ms, Mr and Hc vs. composition.

Here Ms stands for saturation magnetization, A stands for inhomogeneity, χp stands for high field susceptibility, and B stands for anisotropy. A linear relationship between M and 1/H2 from 8 to 18 kOe was observed. As a result, the A/H and χp terms in Eq. (3) can be ignored. The magnetic parameters derived from M vs. H graphs are provided in Table 3 for all the studied samples. The Ms value increases from 67.87 for x = 0.0 sample to 72.38 emu/g (theoretical limit of pure SrM is 72 emu/g (Shirk and Buessem, 1970) for x = 0.20 sample afterward decrease with a calcium content (due to the formation antiferromagnetic secondary phase (α-Fe2O3) beyond x = 0.2). The increase Ms can be discussed as follows: (a) With the increase in dopant Ca2+ concentration upto x = 0.20 (Hooda et al., 2015), the particle size increases. This is because larger particles have a more extensive domain size and therefore align many atomic spins in a fixed direction.

Composition (x)

Hc (Oe)

Ms (emu/g)

Mr (emu/g)

Mr/Ms

Ha (kOe)

0.0

5799

35.55

69.83

0.5090

18.87

0.1

5588

33.95

70.45

0.5102

17.72

0.2

5388

36.42

72.63

0.5014

17.34

0.3

5292

30.91

61.48

0.5027

17.23

0.4

5517

28.61

57.01

0.5018

17.28

0.5

5823

18.42

36.89

0.4993

17.88

The overall magnetic moment increases due the alignment of atomic spins in a particular direction when the magnetic field is applied. (b) At a lower substitution level, some of the Fe3+ sites and Sr2+ sites are occupied by Ca2+ ions because of their relatively small ionic radius at 4f2 spin down and 2a spin-up position (Hooda et al., 2015). When the substitution level is higher, as communicated earlier (Godara et al., 2021) 12 k up spin site and 4f2 down spin sites are also occupied by Ca2+ ions. Ca2+ ions successfully substituted upto x = 0.20 without forming any secondary phase, therefore, these ions are expected to occupy a significant part of the down spin sites. It results in the fall in the oppositely oriented Fe3+ (down spin) ions concentration, consequently an increase in the values of Ms. Conversely to our observation of Ms. A continuous decrease in Ms values in Sr1-xCaxFe11.5Co0.5O19 (x = 0.10–0.50) samples have been reported by Ali et al. (Ali et al., 2013). Whereas Hc values increased to x = 0.20 and then decreased afterward. Other researchers working in M-type hexaferrite groups have also been reported a similar trend (Hooda et al., 2015; Yuping et al., 2018; Kumar et al., 2018). The variation of Ms, Mr, Hc and Ha as a function of ‘x’ for Sr1-xCaxFeO19 (x = 0.0–0.5) is shown in Fig. 6d.

Furthermore, for crystals with hexagonal symmetry, B can be written as:.

Ha and K1 represent to anisotropy field, and anisotropy constant respectively. The value of B can be calculated by plotting M = Ms(1-B/H2) against 1/H2. Furthermore, the anisotropy field, Ha, can be calculated by plugging the value of B into Eq. (4) (Singh et al., 2008). The coercivity (Hc) value is decreased from 5788 to 5292 Oe with an increase in x from 0.0 to 0.3 increases afterward till x = 0.5. It's linked to (a) a decrease in the anisotropy field (Ha) (Iqbal et al., 2009; Abdellah et al., 2018), (b) oxygen vacancies that act as domain wall pinning centers (Kumar et al., 2015), (c) presence of secondary phases and (d) Ca dopant-induced grain growth [Godara et al., 2021]. The presence of Fe3+ on sites of hexagonal unit cells contributing to Ha with a trend of 12 k < 4f1 < 2a < 4f2 < 2b (Li et al., 2000; Singh et al., 2008) causes a decrease in Ha, and different authors have reported significant contributions. From x = 0.0 (18.87 kOe) to 0.3 (17.23 kOe), there is a ≈8 percent drop in the anisotropy field (Ha) as shown in Table 3. On the other hand, doping results in a significant increase in grain size (from 125 (x = 0.0) to 240 nm (x = 0.5)), as shown in Fig. 3. Coercivity has an inverse relationship with grain size (above critical grain size). In the present study, It has been observed that both grain size and anisotropy field (Ha) contribute towards the reduction of coercivity with an increased dopant ion concentration upto x = 0.30. However, the anisotropy field has a greater influence on the mechanism of coercivity than grain from x = 0.0 to x = 0.5. Single domains, highly anisotropic, and magnetically hard materials have a squareness ratio greater than 0.5. However, the material is multi-domain and randomly oriented in nature if the squareness ratio is less than 0.50. Therefore, a high squareness ratio is beneficial to permanent magnets and magnetic recording (Habanjar et al., 2020). The value of squareness ratio is ≈ 0.5 in all the synthesized samples suggesting that the hexaferrite obtained are randomly oriented single domain particles (Chauhan et al., 2018).

4 Conclusion

Sr1-xCaxFe12O19 (x = 0.0–0.5) materials were synthesized from the sol–gel auto-combustion method. Phase purity in Sr1-xCaxFe12O19 samples upto x = 0.20 is confirmed by XRD data beyond which α–Fe2O3 secondary phase is observed. FESEM indicates that grain size monotonically increases with an increase in Ca2+ content. The enhanced grain size as the amount of Ca doping increases is because Ca acts as a grain growth promoter. Non-linear M vs. H loops show the existence of strong magnetic ordering in all the samples. The enhancement in Ms from 67.87 emu/g with x = 0.0 to 72.63 emu/g with x = 0.2 is the replacement of non-magnetic Ca2+ in place of Fe3+ ions at spin down (4f2) sites along with Sr2+ site and increase in domain size with grain growth. The reduction in coercivity from 5799 Oe (at x = 0.00) to 5292 Oe (x = 0.30) has been related to the corresponding decrease in Ha. The large values of Ms (72.63 emu/g) and Hc (5388 Oe) in the x = 0.20 sample are useful for low-cost permanent magnet devices.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge UGC-CAS phase II, DST-FIST, and the Centre for Emerging Sciences for the provision of characterization facilities such as XRD, Raman, FESEM, EDX, and VSM. The authors also extend their sincere appreciation to Researchers Supporting Project number (RSP-2021/391), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Magnetic properties and phase equilibrium in the BaO-CaO-Fe2O3 system. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys.. 1989;22(1):210-215.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rare earth doped metal oxide nanoparticles for photocatalysis: a perspective. Nanotechnol.. 2022;33:142001

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Rietveld refinement, electrical properties and magnetic characteristics of Ca-Sr substituted barium hexaferrites. J. Alloys Compd.. 2012;513:436-444.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Crystal structure refinement, dielectric and magnetic properties of Ca/Pb substituted SrFe12O19 hexaferrites. J. Magn. Magn. Mater.. 2015;387:46-52.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Magnetic properties of barium ferrite formed by crystallization of a glass. J. Am. Ceram. Soc.. 1970;53:192-196.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Structural, magnetic and dielectric properties of Co-Zr substituted M-type calcium hexagonal ferrite nanoparticles in the presence of α-Fe2O3 phase. Ceram. Int.. 2018;44(15):17812-17823.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Static magnetic properties of Co and Ru substituted Ba – Sr ferrite. Mater. Res. Bull.. 2008;43(1):176-184.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Composition and magnetic properties of hexagonal Ca, La ferrite with magnetoplumbite structure. Solid State Commun.. 1980;34(1):49-50.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Structural, electrical, and microstructure properties of nanostructured calcium doped Ba-Hexaferrites synthesized by Sol-Gel method. J. Supercond. Nov. Magn.. 2013;26(11):3277-3286.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Structural, dielectric and Raman spectroscopy of La3+–Ni2+–Zn2+ substituted M-type strontium hexaferrites. Cryst. Res. Technol.. 2021;2100005

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effect of heat-treatment on the magnetic and optical properties of Sr0.7Al0.3Fe11.4Mn0.6O19. Mater. Res. Exp.. 2018;5(8):086106.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Magnetic, Mössbauer and Raman spectroscopy of nanocrystalline Dy3+-Cr3+ substituted barium hexagonal ferrites. Phys. B: Condens. Matter.. 2020;585:412115

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Structural, dielectric, and magneto-optical properties of Cu2+- Er3+ substituted nanocrystalline strontium hexaferrite. Mater. Res. Exp.. 2019;6:056111

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Enhanced dielectric and optical properties of nanoscale barium hexaferrites for optoelectronics and high frequency application. Chinese Phys. B. 2018;27(12):128104.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Structural and dielectric properties of substituted calcium hexaferrites. Int. J. Eng. Res. Technol.. 2019;8:178-182.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of calcination temperature and cobalt addition on structural, optical and magnetic properties of barium hexaferrite BaFe12O19 nanoparticles. Appl. Phys. A Mater. Sci. Process.. 2020;126:402.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Fabrication of M-type ferrites with high La-Co concentration through Ca2+ doping. J. Alloys Compd.. 2018;734:130-135.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effect of temperature on the magnetic properties of strontium hexaferr0000ite synthesized by the Pechini method. Appl. Phys. A Mater. Sci. Process.. 2019;125:711.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Metal organic precursor derived Ba1-xCaxZrO3 (0.05 ≤ x ≤ 0.20) nanoceramics for excellent capacitor applications. J. King Saud Univ. Sci.. 2020;32(3):1937-1943.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Investigation of structural and electrical properties of synthesized Sr-doped lanthanum cobaltite (La1-xSrxCoO3) perovskite oxide. J. king Saud Uni. Sci.. 2021;33(4):101419.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hexagonal ferrites: a review of the synthesis, properties and applications of hexaferrite ceramics. Prog. Mater. Sci.. 2012;57(7):1191-1334.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Raman spectra of sol-gel auto-combustion synthesized Mg-Ag-Mn and BaNd-Cd-In ferrite based nanomaterial. Ceram. Int.. 2020;46:618-621.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effect of lattice strain on structural and magnetic properties of Ca substituted barium hexaferrite. J. Magn. Magn. Mater.. 2018;458:30-38.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effect of heat treatment on properties of Sr0.7Nd0.3Co0.3Fe11.7O19. J. Supercond. Nov. Magn.. 2015;28(10):2935-2940.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Tunable M-type nano barium hexaferrites material by Zn2+/Zr4+ co-doping. Mater. Res. Express.. 2019;6(2019):116111

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of calcium solubility on structural, microstructural and magnetic properties of M-type barium hexaferrite. Ceram. Int.. 2021;47(14):20399-20406.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effect of calcium solubility on structural, microstructure and magnetic properties of SrFe12O19. Phys. B: Condens. Matter. 2022;628:413560.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Impact of Zn2+-Zr4+ substitution on M-type barium strontium hexaferrite's structural, surface morphology, dielectric and magnetic properties. Results Phys.. 2021;22:103892.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Structural and magnetic behavioral improvisation of nanocalcium hexaferrites. Mater. Sci. Eng. B Solid-State Mater. Adv. Technol.. 2010;168(1-3):156-160.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Solvothermal synthesis, optical and magnetic properties of nanocrystalline Cd1−xMnxO (0.04 < x = 0.10) solid solutions. J. Alloys Compd.. 2013;558:117-124.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Optical and multiferroic properties of Gd-Co substituted barium hexaferrite. Cryst. Res. Technol.. 2017;52(9):1700098.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Trudel, T.T.C., Mohammed, J., Hafeez, H.Y., Bhat, B.H., Godara, S.K., Srivastava, A.K., 2019. Structural, dielectric, and magneto-optical properties of Al-Cr substituted M-type barium hexaferrite. 216 (26), 1800928. doi: 10.1002/pssa.201800928.

- Structural and magnetic properties of La-Co substituted Sr-Ca hexaferrites synthesized by the solid state reaction method. Mater. Res. Bull.. 2014;59:37-41.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Site preference and magnetic properties for a perpendicular recording material: BaFe12-xZnx/2Zrx/2O19 nanoparticles. Phys. Rev. B – Condens. Matter Mater. Phys.. 2000;62:6530-6537.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]