Translate this page into:

Temperature mediated influence of mycotoxigenic fungi on the life cycle attributes of Callosobruchus maculatus F. in stored chickpea

⁎Corresponding author. qamarsaeed@bzu.edu.pk (Qamar Saeed)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Environmental factors (biotic and abiotic) are major depletion reasons in granaries. Fungi and insect pests act synergistically in deterioration of grains in storages which results in nutritional damage to the stored food which becomes unpalatable for the consumer. There is a need to establish a timeline for synergistic damage caused by insect pests and mycotoxigenic fungi for better management. For this purpose, interaction of mycotoxigenic fungi (Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus niger, Penicillium digitatum and Alternaria alternata) with Callosobruchus maculatus (F.) (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) was studied at different temperatures. Development of C. maculatus was observed on fungus inoculated and uninoculated C. arietinum seeds. In fungus inoculated grains the development (Fecundity, larval emergence, pupation rate and adult emergence) of C. maculatus was found more better as compared on uninoculated grain. The population of C. maculatus was decreased by increase in temperature but high temperatures favours more fungi developments. More egg laying was observed at 27 °C and 33 °C. At tested temperatures, larval emergence was high as compared to other observed life attributes. Infestation of A. flavus and A. niger was also increased with increase of temperatures. Penicillium digitatum and A. alternata infestation were increased in the C. arietinum at 27 °C and 30 °C respectively. This study will help in measuring the control practices of fungi and insect pest infestations in stored C. arietinum (chickpea) in Pakistan.

Keywords

Insect microbial interaction

C. maculatus

Growth parameters

Ecophysiological factors

1 Introduction

Pakistan is fourth in chickpea (Cicer arietinum Linnaeus) production worldwide. It has high carbohydrate (62.34 %) and protein contents (23.67 %) (El-adawy, 2002) (Alajaji and El-Adawy, 2006; FAO, 2018). Pakistan faces considerable losses (15–55 %) in chickpea crops during storage (Vanzetti et al., 2017). Contamination of stored commodities is mostly due to microflora and insect infestations (Bhat, 1988; Delouche, 1980; Mills, 1986; Tuda, 1996). Mycotoxins are non-volatile secondary metabolites, produced by filamentous fungi which reduce the quality of stored food by damaging their physical appearance and chemical composition (Bräse et al., 2009). Mycotoxins mediated semiochemicals are considered as an indicator of rotten odor in grains and facilitate interaction among insects and fungus species (Bennett and Inamdar, 2015; Bennett et al., 2012).

In stored commodities, the species of genus Aspergillus and Penicillium are more proliferating due to high relative humidity and mycotoxins (Dawar et al., 2007; Kumar et al., 2009; Patil et al., 2012; Shukla et al., 2012). Aspergillus flavus is responsible for 64 % more aflatoxin production in stored chickpea (Ramirez et al., 2018). Chickpea contaminated with toxigenic fungi have an detrimental effects on human health and animals (Urooj et al., 2015).

The granivorous cowpea weevil, Callosobruchus maculatus (F.) (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) is the considerable causative agent of severe losses in seed germination, weight and nutritional level of legumes (Généfol et al., 2018; Staneva, 1982; Valencia et al., 1986; Murugesan et al., 2021). The C. maculatus can destroy dry beans in tropical and arid climatic zones, especially in stores (Tuda et al., 2006). Resistance against the stress condition of store houses is found in C. maculatus (Dongre et al., 1996). The penetration of storage fungi in stored commodities occurs due to the mishandling after harvest, presence of dust residues, cracks in seed coat because of mechanical handling and insects (Woloshuk and Martínez, 2012).

Temperature is also a fundamental aspect related to insect physiology (Ratte, 1984) and biochemistry (Downer and Kallapur, 1981). The various ranges of temperature affect the survival of Bruchidae species and insect activities (Giga and Smith, 1987; Miyatake et al., 2008; Soares et al., 2015). Development of C. maculatus is highly responsive to ranges of temperature which are also responsible for fungal development during post-harvest practices (Kistler, 1995; Sautour et al., 2001; Umoetok Akpassam et al., 2017). The well-studied temperature variables for all pathogenic microbes ranges from 15 to 37 °C. The optimum temperature for growth of A. flavus is 37 °C, while Penicillium species are also developed at lower temperatures i.e., from room temperature to 0 °C (Asurmendi et al., 2015; Lahouar et al., 2016; Palou, 2014).

Current study was designed to interpret the relationship between fungal species (Penicillium digitatum, Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus niger, Alternaria alternata) and population build-up of C. maculatus in stored chickpea at different temperatures (25, 27, 33 and 35 °C) at constant level of R.H. (70 %). Current findings will be helpful in developing effective IPM strategy for C. maculatus and fungal infestation in stored products.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Insect culture

Callosobruchus maculatus was cultured on sanitized chickpea grains under constant laboratory conditions (25 ± 5 °C and 55 ± 5 % R.H.) to obtain a uniform population. Males and female beetles were separated using the standard procedures (Beck and Blumer, 2011).

2.2 Collection of chickpeas

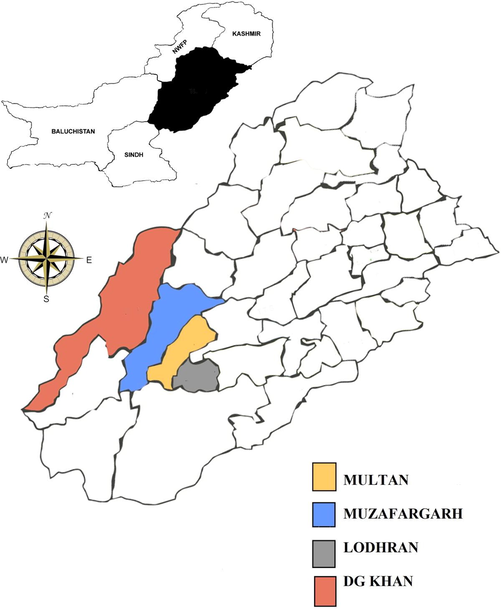

For experiment, stored chickpea (‘kabuli’ variety) (stored for one year) was obtained from the retailor shop at four different locations (Fig. 1) (Dera Ghazi Khan, Lodhran, Muzaffargarh, and Multan) and was kept at 25 ± 5 °C and 55 ± 5 % R.H. in Ecotoxicology Laboratory, Department of Entomology, Bahauddin Zakariya University (BZU) Multan, Pakistan. All the samples were stored in autoclaved cylindrical glass jars (32 × 23 × 23 cm).

Locations for C. arietinum sampling in Punjab Pakistan.

2.3 Isolation of mycotoxigenic fungi

To isolate fungi from C. maculatus, seven adult insects were made sterile with 2 % solution of sodium hypochlorite, washed twice with distilled water, dried on blotter paper, crushed and placed on PDA (Potato Dextrose Agar) plate. The PDA plates were prepared by potato starch (125 g), dextrose (10 g) and agar (7.5 g) in 500 ml distilled water.

To isolate fungi from C. arietinum, five grains were disinfected with 2 % sodium hypochlorite, washed with distilled water twice, dried on blotting paper and placed on PDA plates for fungal growth observation (Bosly and Kawanna, 2014; Taylor and Sinha, 2009). All the isolation procedures were done in a horizontal laminar flow cabinet (Airstream® LHG) (Lamboni and Hell, 2009). The isolation procedure for both insects and grains were replicated 10 times.

2.4 Identification of mycotoxigenic fungi

Identification of different fungi spp. was performed at Plant Pathology Department of Bahauddin Zakariya University (BZU) Multan, Pakistan. Mycological evaluation through microscopic examination was done by staining the hyphae with methylene blue on glass slides from fresh fungal cultures (Morishita and Sei, 2006).

2.5 Purification of mycotoxigenic fungi

Fungal cultures obtained through isolation were purified to avoid other microbes. The PDA plates with required fungal species were separated through sterile needles and incubated at 25 °C and observed daily (Ko et al., 2001).

2.6 Percentage of fungus

Fungal growth frequency (isolated from C. maculatus and C. arietinum) was determined by the following equation (Eq. (1)) (Ahmad and Singh, 1991):

2.7 Spore suspension

Fungi isolated from C. arietinum and C. maculatus were used for spore suspension. The suspensions were prepared from 7 days old cultures of fungus. Fungal spores of mycotoxigenic fungi species were scraped with the help of glass slide by adding 20 ml autoclaved distilled water, and then solution was stirred in magnetic stirrer until conidia become separated from PDA. After agitation, impurities of suspension were removed by filtering it through filter paper. The numbers of spores were counted under a light microscope through haemocytometer.

2.8 Inoculation of C. arietinum grains

Spore suspension was diluted to obtain 5 × 103 spores/ml to inoculate C. arietinum. Cicer arietinum inoculated with fungal cultures by adding 3 ml of spore suspension per 100 g grains in glass jar (12.7 × 8.1 × 8.1 cm) (Nesci and Montemarani, 2011).

2.9 Influence of temperature on growth of C. maculatus and mycotoxigenic fungi

The normal prevailing temperatures (27, 30, 33 and 35 °C) were tested for the development of C. maculatus and mycotoxigenic fungi, at 70 % R.H. All the selected temperatures were maintained in a growth chamber (Versatile environmental test chamber, MLR-352H, Japan).

2.10 Extent of fungi on life cycle of C. maculatus

Five pairs of surface sterilized (2 % sodium hypochlorite) adults of C. maculatus were introduced into glass jars (12.7 × 8.1 × 8.1 cm), each containing 100 g of inoculated C. arietinum, and were removed after 24 h (Tsai et al., 2007). All the experimental units were maintained in a growth chamber (Versatile environmental test chamber, MLR-352H, Japan) with four constant temperatures 27 °C, 30 °C, 33 °C and 35 °C and 70 % R.H. Cicer arietinum were checked for numbers of C. maculatus eggs, larvae, pupae and adults by dissecting grains along with growth of fungal species (Howe and Currie, 1964). Each temperature treatment was replicated 4 times.

2.11 Statistical analysis

Incidence (%) of fungal species in C. maculatus adults and C. arietinum were analysed via frequency equation mentioned in section 2.6. While Chi square test and two-way ANOVA of the fungal isolation frequency were performed by subjecting data to a computational based software SPSS (SPSS Version 7.0). As the data was normal so data was not subjected to normality test. Developmental activity of C. maculatus and fungal species at different temperatures were calculated through software (SAS Institute, 2000).

3 Results

3.1 Isolation of mycotoxigenic fungi

3.1.1 From C. arietinum grains

Cicer arietinum was evaluated for fungal colonies. A. flavus, F. oxysporum, P. digitatum and A. alternata were prominent in seed. Samples of C. arietinum from all localities were high in A. flavus, A. niger, A. alternata, P. digitatum and F. oxysporum. Results revealed that samples of were significantly (F = 32.009; df = 4 (20); P < 0.001) highly infested with A. flavus (52.3 %) followed by A. niger (27.3 %), F. oxysporum (21.33) and P. digitatum (22.0 %). While A. alternata (8.0 %) exhibited the lowest frequency (Table 1). Means within a column followed by the same letter are not significantly different from each other (SPSS software at P = 0.05).

Species

Multan

(n = 75)Muzaffargarh

(n = 75)Lodhran

(n = 75)DG khan

(n = 75)Total

Isolates

(n = 300)IsolationFrequency

(%)

A. flavus

72

28

27

30

157

52.3 ± 14.5a

A. niger

33

15

21

13

82

27.3 ± 6.0b

A.alternata

10

3

7

4

24

8.0 ± 2.1b

F. oxysporum

30

8

7

19

64

21.3 ± 7.2b

P. digitatum

30

11

11

14

66

22.0 ± 6.1b

3.1.2 From C. maculatus

Fungal growth observation from the body of C. maculatus revealed that A. flavus was most frequent (71.43 %) while A. alternata was rarely isolated from adults (4.64) (Table 2). Diversity of fungi on the bodies of C. maculatus was irrespective of the gender of insect (X2 = 6.339a; df = 4; P greater than 0.175). (Chi square test at P = 0.05).

Species

No. of isolates

IsolationFrequency

(%)

Female

(n = 140)Male

(n = 140)Total isolates

(n = 280)

A. flavus

98

102

200

71.43

A. niger

20

24

44

15.71

A. alternata

3

10

13

4.64

F. oxysporum

24

37

61

21.79

P. digitatum

32

26

58

20.7

3.2 Interaction among mycotoxigenic fungi and C. maculatus in C. arietinum grains at different temperatures

3.2.1 Developmental period of C. maculatus

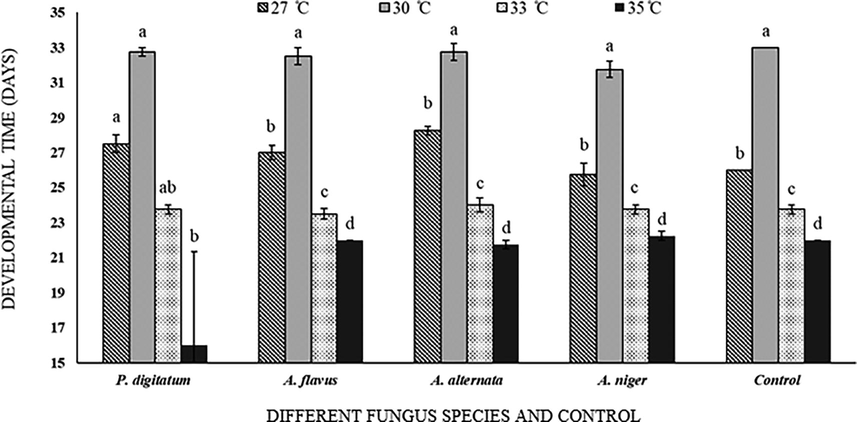

Life cycle attributes of (egg, larvae, pupae, and adult stages) C. maculatus were tested on inoculated C. arietinum grains at four different temperatures (27, 30, 33, 35 °C). Population was developed at all tested temperatures with significant responses (F = 81.85; df = 3(60); P < 0.001). At highest tested temperature the life period of C. maculatus was shortened. Similarly, intensification in temperature also increased the development of A. flavus and A. niger in grains. The life period of C. maculatus was 33 days (highest recorded days) at 30 °C. Impact of fungal growth was found non-significant (F = 1.51; df = 12 (60); P = 0.146) with the life cycle attributes of C. maculatus and all tested temperatures (Fig. 2).

Callosobruchus maculatus development rate on fungal infected and non-infected C. arietinum at different temperatures. Bars on each column represents standard error (±SE). Duncan test at P = 0.05. (Different fungus species and control are present on X-axis, developmental time at different temperatures is on Y-axis).

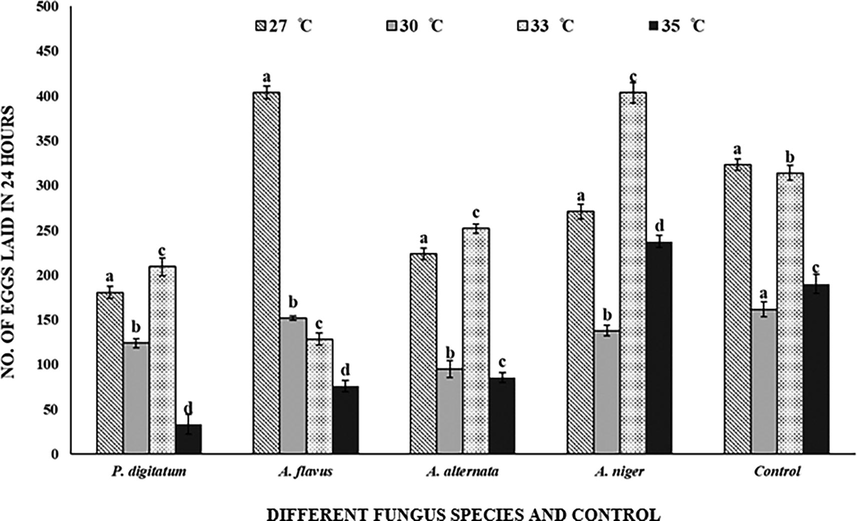

3.2.2 Fecundity of C. maculatus

Oviposition rates of C. maculatus were significantly affected (F = 564.37; df = 3(60); P < 0.001) at all tested temperatures. The females of C. maculatus preferred inoculated C. arietinum more than sterilized C. arietinum grains for oviposition at all temperatures treatments. At 27 °C and 33 °C, oviposition was 403.75 on C. arietinum grains inoculated with A. flavus and A. niger. Reduction in the oviposition occurs at 35 °C in inoculated and control C. arietinum. P. digitatum inoculated grains exhibited a few oviposition (33.25). Oviposition rate was highly significant (F = 83.05; df = 12 (60); P < 0.001) with relation to fungal inoculation (F = 192.23; df = 4 (60); P < 0.001) and temperature (Fig. 3).

Callosobruchus maculatus egg laying on fungal infected and non-infected C. arietinum at different temperatures. Bars on each column represents standard error (±SE). Duncan test at P = 0.05. (Different fungus species and control are present on X-axis, developmental time at different temperatures is on Y-axis).

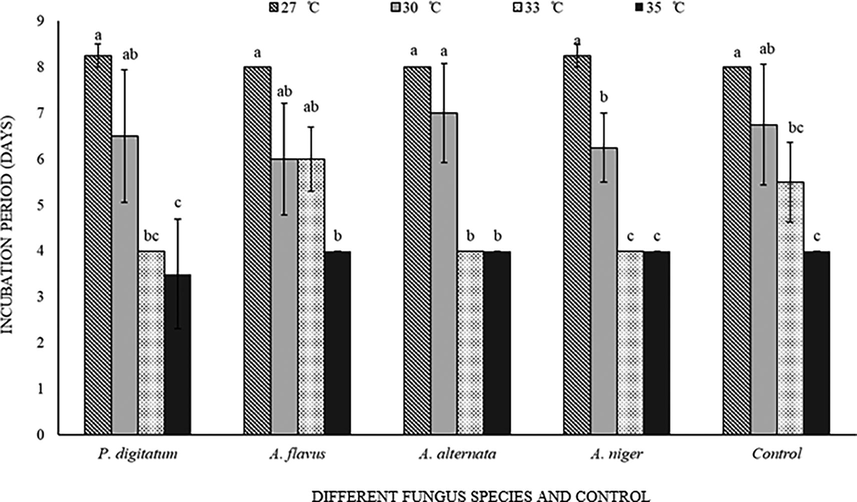

3.2.3 Incubation period

Incubation period of C. maculatus were not significantly (F = 0.40; df = 4 (60); P = 0.80) influenced by interaction of fungi and temperature (F = 0.66; df = 12 (60); P = 0.78). Highest incubation period was of 8.25 days at 27 °C and same number of days were observed in presence of all tested fungal species on C. arietinum. Temperature ranges exhibited highly significant (F = 35.93; df = 3 (60); P < 0.001) effect on the incubation period of C. maculatus. Increase in temperature was also decreased the incubation period of C. maculatus as observed in P. digitatum infested C. arietinum grains was shows shortest incubation period (3.5 days) at 35 °C (Fig. 4).

Callosobruchus maculatus incubation period on fungal infected and non-infected C. arietinum at different temperatures. Bars on each column represents standard error (±SE). Duncan test at P = 0.05. (Different fungus species and control are present on X-axis, developmental time at different temperatures is on Y-axis).

3.2.4 Larval emergence of C. maculatus

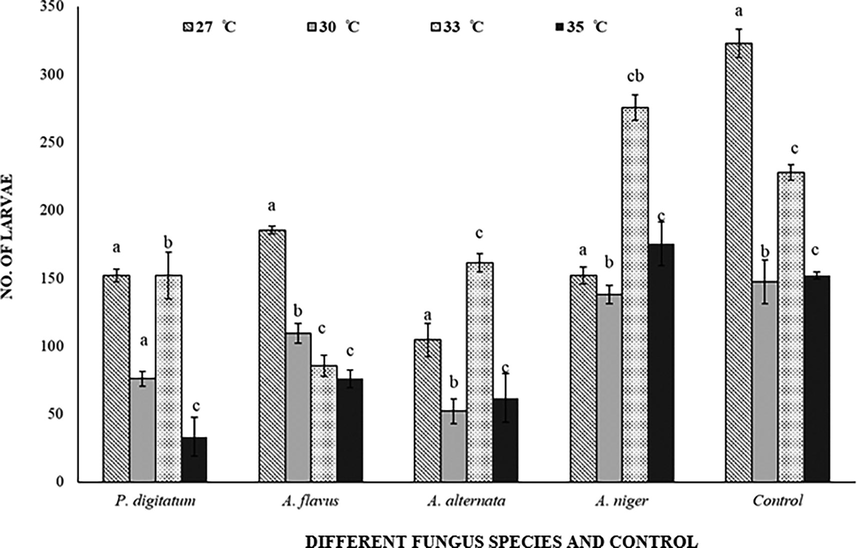

Larvae of C. maculatus were significantly influenced due to temperatures (F = 98.15; df = 3 (60); P < 0.001) and mycotoxigenic fungi (F = 104.49; df = 4 (60); P < 0.001) infestation in C. arietinum. Fungal prevalence in grains at different temperatures decreased the larvae emergence. Moreover, opposite results for larvae emergence were observed in instances of non-inoculated (323 at 27 °C) and A. niger inoculated (275.5 at 33 °C) C. arietinum. The successive highest rate of larvae emergence was observed in C. arietinum infested with A. niger. Numbers of larvae emergence was also significantly affected because of interaction among fungi and temperatures (F = 19.38; df = 12 (60); P < 0.001). The results also revealed the lowest number of larvae (33.25) emergence in P. digitatum infested C. arietinum at 35 °C (Fig. 5).

Response of Callosobruchus maculatus (larval population) on fungal infected and non-infected C. arietinum at different temperatures. Bars on each column represents standard error (±SE). Duncan test at P = 0.05. (Different fungus species and control are present on X-axis, developmental time at different temperatures is on Y-axis).

3.2.5 Pupation of C. maculatus

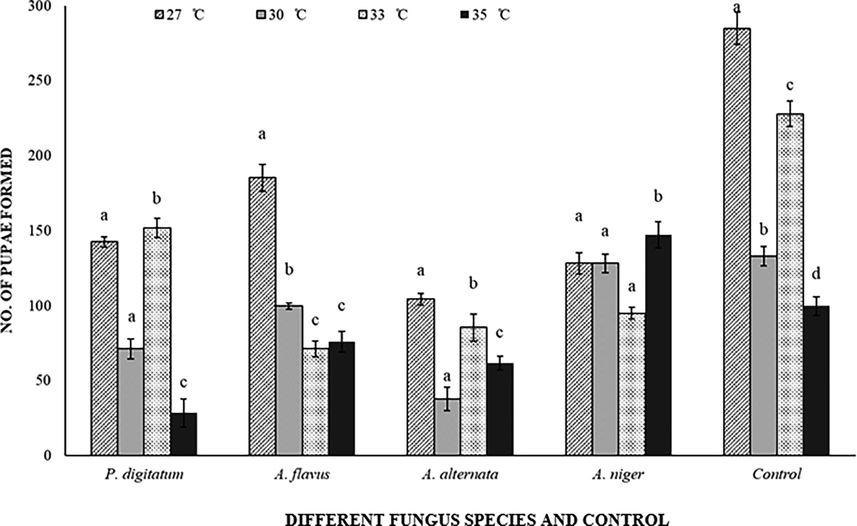

The mycotoxigenic fungi (F = 153.97; df = 4 (60); P < 0.001), temperatures (F = 158.96; df = 3 (60); P < 0.001) and their interaction (F = 38.90; df = 12 (60); P < 0.001) exhibited highly significant effects towards pupation rate of C. maculatus. However, C. arietinum infested with P. digitatum and A. alternata showed the lowest pupation rate was 28.5 and 38, respectively, at 35 °C. High numbers of pupae emerged at 27 °C in inoculated and un-inoculated C. arietinum as compared to other temperatures (Fig. 6).

Response of Callosobruchus maculatus (pupal population) on fungal infected and non-infected C. arietinum at different temperatures. Bars on each column represents standard error (±SE). Duncan test at P = 0.05. (Different fungus species and control are present on X-axis, developmental time at different temperatures is on Y-axis).

3.2.6 Adult emergence

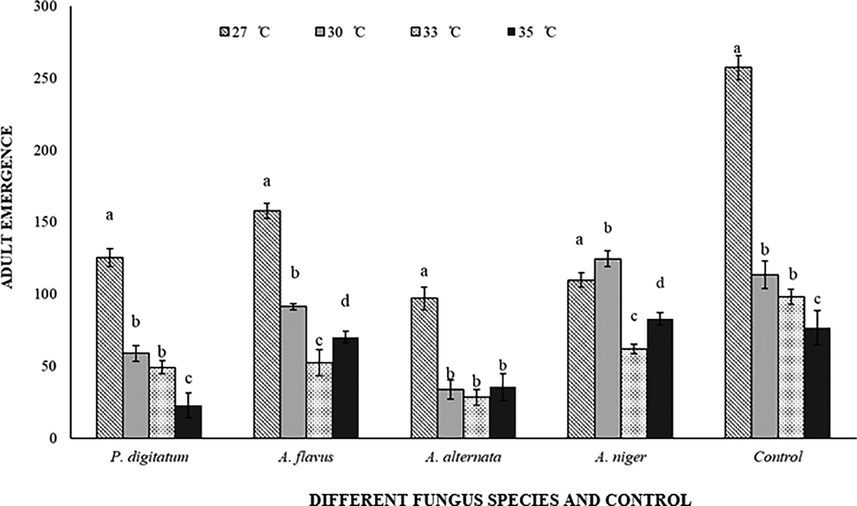

Adult emergence of C. maculatus were inversely correlated with fluctuating temperatures (F = 202.02; df = 3 (60); P < 0.001), mycotoxigenic fungi (F = 97.95; df = 4 (60); P < 0.001) (F = 18.30; df = 4 (60); P < 0.001) and their interactions (F = 17.37; df = 12 (60); P < 0.001). Results demonstrated that, at 27 °C maximum adults were emerged in inoculated and non-inoculated C. arietinum. However, the lowest adult emergence rate at 35 °C in P. digitatum inoculated C. arietinum was 23 (Fig. 7).

Response of Callosobruchus maculatus (adult emergence) on fungal infected and non-infected C. arietinum at different temperatures. Bars on each column represents standard error (±SE). Duncan test at P = 0.05. (Different fungus species and control are present on X-axis, developmental time at different temperatures is on Y-axis).

4 Discussion

Results of the current study revealed high frequencies of A. flavus and A. niger isolates from C. maculatus adults. Similar results reported that infestation of mycotoxigenic fungi in Triticum aestivum observed because of T. castaneum and Sitophilus granarius activities (Agrawal et al., 1957; Bosly and Kawanna, 2014). The presence of mycotoxigenic fungi in an insect body illustrates that insects were able to transfer fungal flora in grains. Red flour beetle had been associated with dissemination of mycotoxigenic fungi to their hosts (Bosly and Kawanna, 2014) and also observed in stored rice grains (Yun et al., 2018). Larvae, pupae and adults of C. maculatus were significantly affected by the infestation of mycotoxigenic fungi.

Insect pests have intrinsic ability to develop and reproduce to change in temperature and time progressively (Burges, 2008). Temperature is inversely interacting with growth rate of insects. Results explain that C. maculatus completed its life cycle on all tested fungus and temperature parameters. The progressive period of C. maculatus was shorter on all infested and non-infested C. arietinum at 35 °C and 70 % R.H. Shortest life period of Cadra cautella were demonstrated at 30 °C and 70 % R.H. (Burges and Haskins, 1965). Ahasverus advena also complete their life cycle on different concentrations of Aflatoxin B1 infested grains and the shortest life cycle was observed at 30 °C (Jacob, 1996; Zhao et al., 2018). Emergence of larvae was high at 27 °C on sterilized C. arietinum as well as on C. arietinum infested with A. niger at 33 °C. Similar results were observed in development of Trogoderma granarium on broken wheat grains at 35 °C while maximum fecundity and larvae emergence was evaluated at 30 °C (Riaz et al., 2014). The infestation of mycotoxigenic fungi was able to influence the development period of C. maculatus in stored grains under selected temperature ranges.

Longest development period of C. maculatus was analysed 33 days at 30 °C and more than 25 days at 27 °C on inoculated and non-inoculated C. arietinum. C. maculatus showed an incubation period of more than 6 days at 30 °C on all tested parameters. This is higher than other pests including Chilo partellus was showed shortest incubation period (4 days) at 30 °C but a similar development period of more than 30 days was observed at 30 °C at 80 % R.H. (Tamiru et al., 2012). Maximum progress rate of A. flavus was noticed at 35 °C (Mannaa and Kim, 2018). A. alternata shows maximum growth rate at 25 °C on Glycine max (Oviedo et al., 2011). Meanwhile germination of Penicillium spp. was observed at 30 °C at 75 % humidity (Pasanen et al., 1991). Fusarium spp. was not showed any germination at temperature up to 25 °C on G. max medium (Garcia et al., 2012) that’s why we do not select this species as the medium for C. maculatus growth on these temperature ranges.

Temperature influenced the fecundity of C. maculatus more than humidity. Temperature and suitable host preferences are the most considerable factors related to the development and oviposition of C. maculatus (Giga and Smith, 1987; Mam and Mohamed, 2015). The results presented maximum oviposition and larvae rate of C. maculatus on A. flavus inoculated C. arietinum at 27 °C as well as on A. niger at 33 °C. High numbers of larvae, pupae and adults were observed on sterilized C. arietinum. C. maculatus preferred A. flavus and A. niger infested C. arietinum more than control for oviposition. This is in contrast to corns infested with A. halophilicus were more suitable for the oviposition of P. interpunctella while a high development rate was observed at autoclaved corn (Abdel-Rahman and Hodson, 1969). T. stercorea showed minimum oviposition and maximum numbers of larvae on A. flavus at 30 °C. Average oviposition rate of C. maculatus on the P. digitatum (33–209) was highest as compared to T. stercorea was lowest on P. purpurogenum (42). Minimum larvae emergence was observed in T. stercorea on P. purpurogenum (Jacob, 1988; Tsai et al., 2007) as the same results were also observed for C. maculatus on P. digitatum C. arietinum.

C. maculatus preferred to oviposit at 30 °C and 35 °C while maximum oviposition was observed at 30 °C on sterilized C. arietinum (Chandrantha et al., 1987; Lale and Vidal, 2003). Researchers also found that A. advena and Cryptolestes ferrugineus were not able to oviposit on the A. flavus and A. niger isolates as observed in case of C. maculatus (David, 1974; Loschiavo and Sinha, 1966).

5 Conclusion

Management of stored product pests is necessary to prevent postharvest losses (Batool et al., 2021) and development of mycotoxigenic fungi. More than 70 % of C. arietinum deteriorates because of mycotoxigenic fungi and C. maculatus in houses, markets and stores. All the identified fungi species are well known to produce mycotoxins and reduction in the nutritional value of C. arietinum. A reduced amount of fungal growth on non-infested autoclaved chickpea grains (control) was observed at all selected temperatures even in presence of weevil. Preventive measures for both pests should be applied at commercial levels on the tested temperatures ranges in stores, houses and markets.

-

C. maculatus was able to reproduce in both inoculated and non-inoculated grains on all selected temperatures.

-

Market stored chickpea grains were found with more than 50 % frequency of mycotoxigenic fungi while this percentage increased to 70 % when insects come in contact with the grains in storages

-

C. maculatus carr. fungus in body and the relationship between both developed early at 35 °C causing high quality damage of C. arietinum.

Acknowledgments

The research was supported by Department of Entomology, Faculty of Agriculture Sciences and Technology, Bahauddin Zakariya University Multan, Pakistan. The authors also extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Khalid University Saudi Arabia for funding this work through Large Groups Project under grant number RGP.2/28/43.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- The relationship between Plodia interpunctella (Phycitidae) and stored-grain fungi. J. Sored. Prod. Res.. 1969;4:331-337.

- [Google Scholar]

- Grain storage fungi associated with the Grainary Weevil. J. Econ. Entomol.. 1957;50:659-663.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mycofloral changes and aflatoxin contamination in stored chickpea seeds. Food. Addit. Contam.. 1991;8:723-730.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nutritional composition of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) as affected by microwave cooking and other traditional cooking methods. J. Food. Compos. Anal.. 2006;19:806-812.

- [Google Scholar]

- Influence of Listeria monocytogenes and environmental abiotic factors on growth parameters and aflatoxin B1 production by Aspergillus flavus. J. Stored. Prod. Res.. 2015;60:60-66.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nanoencaspsulation of cysteine protease for the management of stored grain pest, Sitotroga cerealella (Olivier) Journal of King Saud University-Science. 2021;33(4):101404.

- [Google Scholar]

- A Handbook on Bean Beetles, Callosobruchus maculatus, Caryologia. National Science Foundation; 2011.

- Are some fungal volatile organic compounds (VOCs) mycotoxins? Toxins. 2015;7:3785-3804.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fungal and bacterial volatile organic compounds: An overview and their role as ecological signaling agents. In: Fungal Associations (2nd eds.). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2012. p. :373-393.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mould deterioration of agricultural commodities during transit: problems faced by developing countries. Int. J. Food Microbiol.. 1988;7:219-225.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fungi species and red flour beetle in stored wheat flour under Jazan region conditions. Toxicol. Ind. Health.. 2014;30:304-310.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chemistry and biology of mycotoxins and related fungal metabolites. Chem. Rev.. 2009;109:3903-3990.

- [Google Scholar]

- Development of the khapra beetle, Trogoderma granarium, in the lower part of its temperature range. J. Stored Prod. Res.. 2008;44:32-35.

- [Google Scholar]

- Life-cycle of the tropical warehouse moth, Cadra cautella (Wlk.), at controlled temperatures and humidities. Bull. Entomol. Res.. 1965;55:775-789.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of temperature and host seed species on the fecundity of Callosobruchus maculatus (F.) Proc. Anim. Sci.. 1987;96:221-227.

- [Google Scholar]

- Development and oviposition of Ahasverus advena (Waltl)(Coleoptera, Silvandiae) on seven species of fungi. J. Stored Prod. Res.. 1974;10:17-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Seed borne fungi associated with chickpea in Pakistan. Pak. J. Bot.. 2007;39:637-643.

- [Google Scholar]

- Environmental effects on seed development and seed quality. Hortscience. 1980;15:13-18.

- [Google Scholar]

- Identification of resistant sources to cowpea Weevil (Callosoburcchus maculatus (F.)) in Vigna sp. and inheritance of their resistance in black gram (Vigna mung var. mungo) J. Stored Prod. Res.. 1996;32:201-204.

- [Google Scholar]

- Temperature-induced changes in lipid composition and transition temperature of flight muscle mitochondria of Schistocerca gregaria. J. Therm. Biol.. 1981;6:189-194.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nutritional composition and antinutritional factors of chickpeas (Cicer arietinum L.) undergoing different. Plant. Food. Hum. Nutr.. 2002;57:83-97.

- [Google Scholar]

- FAO, 2018. Pakistan Fourth Largest Producer of Chickpeas in World. FAO Report [WWW Document]. Food Agric. Organ. URL https://www.brecorder.com/2018/12/13/458753/pakistan-fourth-largest-producer-of-chickpeas-in-world-fao-report/. (accessed 8.12.20).

- Impact of cycling temperatures on Fusarium verticillioides and Fusarium graminearum growth and mycotoxins production in soybean. J. Sci. Food. Agric.. 2012;92:2952-2959.

- [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of the effect of fungal parasites and Callosobruchus maculatus Fab. on the physiological and biochemical parameters of cowpea (Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp.) seeds in Côte d’Ivoire. Int. J. Sci.. 2018;4:34-46.

- [Google Scholar]

- Egg production and development of Callosobruchus rhodesianus (Pic) and Callosobruchus maculatus (F.) (Coleoptera: Bruchidae) on several commodities at two different temperatures. J. Stored Prod. Res.. 1987;23:9-15.

- [Google Scholar]

- Some laboratory observations on the rates of development, mortality and oviposition of several species of Bruchidae breeding in stored pulses. Bull. Entomol. Res.. 1964;55:437-477.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effect of temperature and humidity on the developmental period and mortality of Typhaea stercorea (L.) (Coleoptera: Mycetophagidae) J. Stored Prod. Res.. 1988;24:221-224.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effect of constant temperature and humidity on the development, longevity and productivity of Ahasverus advena (Waltl.) (coleoptera: silvanidae) J. Stored Prod. Res.. 1996;32:115-121.

- [Google Scholar]

- Influence of temperature on populations within a guild of mesquite bruchids (Coleoptera: Bruchidae) Environ. Entomol.. 1995;24:663-672.

- [Google Scholar]

- A simple technique for purifying fungal cultures contaminated with bacteria and mites. J. Phytopathol.. 2001;510:1969-1970.

- [Google Scholar]

- Use of essential oil from Mentha arvensis L. to control storage moulds and insects in stored chickpea. J. Sci. Food Agric.. 2009;89:2643-2649.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of temperature, water activity and incubation time on fungal growth and aflatoxin B1 production by toxinogenic Aspergillus flavus isolates on sorghum seeds. Rev. Argent. Microbiol.. 2016;48:78-85.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of constant temperature and humidity on oviposition and development of Callosobruchus maculatus (F.) and Callosobruchus subinnotatus (Pic) on bambara groundnut, Vigna subterranea (L.) Verdcourt. J. Stored Prod. Res.. 2003;39:459-470.

- [Google Scholar]

- Propagation of mycotoxigenic fungi in maize stores by post-harvest insects. Int. J. Trop. Insect Sci.. 2009;29:31-39.

- [Google Scholar]

- Feeding, oviposition, and aggregation by the rusty grain beetle, Cryptolestes ferrugineus (Coleoptera: Cucujidae) on seed-borne fungi1. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am.. 1966;59:578-585.

- [Google Scholar]

- Susceptibility of certain pulse grains to Callosobruchus maculatus (F.) (Bruchidae: Coleoptera), and influence of temperature on its biological attributes. J. Appl. Plant Prot.. 2015;3:9-15.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of temperature and relative humidity on growth of Aspergillus and Penicillium spp. and biocontrol activity of Pseudomonas protegens AS15 against Aflatoxigenic Aspergillus flavus in stored rice grains. Mycobiology. 2018;46:287-295.

- [Google Scholar]

- Postharvest insect-fungus associations affecting seed deterioration. Physiol. Interact. Affect. Seed. Deterior.. 1986;4:39-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Negative relationship between ambient temperature and death-feigning intensity in adult Callosobruchus maculatus and Callosobruchus chinensis. Physiol. Entomol.. 2008;33:83-88.

- [Google Scholar]

- Microreview of Pityriasis versicolor and Malassezia species. Mycopathology. 2006;162:373-376.

- [Google Scholar]

- Insecticidal and repellent activities of Solanum torvum (Sw.) leaf extract against stored grain Pest, Callosobruchus maculatus (F.)(Coleoptera: Bruchidae) Journal of King Saud University-Science. 2021;33(3):101390.

- [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of mycoflora and infestation of insects, vector of Aspergillus section Flavi, in stored peanut from Argentina. Mycotoxin Res.. 2011;27:5-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Influence of water activity and temperature on growth and mycotoxin production by Alternaria alternata on irradiated soya beans. Int. J. Food. Microbiol.. 2011;149:127-132.

- [Google Scholar]

- Penicillium digitatum, Penicillium italicum (Green Mold, Blue Mold), Postharvest Decay: Control Strategies. Elsevier; 2014. p. :45-102.

- Laboratory studies on the relationship between fungal growth and atmospheric temperature and humidity. Environ. Int.. 1991;17:225-228.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mycoflora associated with Pigeon pea and Chickpea. Int. Multidiscip. Res. J.. 2012;2:10-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Science Direct Impact of toxigenic fungi and mycotoxins in chickpea: a review. Cur. Opin. Food. Sci.. 2018;23:32-37.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of temperature on the development, survival, fecundity and longevity of stored grain pest, Trogoderma granarium. Pak. J. Zool.. 2014;46:1485-1489.

- [Google Scholar]

- A temperature-type model for describing the relationship between fungal growth and water activity. Int. J. Food. Microbiol.. 2001;67:63-69.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antifungal, aflatoxin inhibition and antioxidant activity of Callistemon lanceolatus (Sm.) Sweet essential oil and its major component 1,8-cineole against fungal isolates from chickpea seeds. Food. Control.. 2012;25:27-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of temperature on the development and feeding behavior of Acanthoscelides obtectus (Chrysomelidae: Bruchinae) on dry bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) J. Stored. Prod. Res.. 2015;61:90-96.

- [Google Scholar]

- Studies on the food-plants of the cowpea weevil Callosobruchus maculatus F. (Coleoptera, Bruchidae) Rasteniev’dni Nauk.. 1982;19:111-119.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of temperature and relative humidity on the development and fecundity of Chilo partellus (Swinhoe) (Lepidoptera: Crambidae) Bull. Entomol. Res.. 2012;102:9-15.

- [Google Scholar]

- Food Additives and Contaminants Incidence of mycotoxins in maize grains in Bihar State. India. India. Food Addit. Contam. 2009:37-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of three stored-grain fungi on the development of Typhaea stercorea. J. Stored. Prod. Res.. 2007;43:129-133.

- [Google Scholar]

- Temporal/Spatial Structure and the Dynamical Property of Laboratory Host-Parasitoid Systems. Res. Popul. Ecol.. 1996;38:133-140.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evolutionary diversification of the bean beetle genus Callosobruchus (Coleoptera: Bruchidae): Traits associated with stored-product pest status. Mol. Ecol.. 2006;15:3541-3551.

- [Google Scholar]

- Response of Callosobruchus maculatus (F.) to varying temperature and relative humidity under laboratory conditions. Arch. Phytopathol. Plant Prot.. 2017;50:13-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- Occurrences of mycotoxins contamination in crops from Pakistan: A review. J. Agric. Environ. Sci. 2015;15:1204-1212.

- [Google Scholar]

- Valencia, G., Cardona Mejía, C., Schoonhoven, A. V., 1986. Main insect pests of stored beans and their control [tutorial unit]. Cent. Int. Agric. Trop. (CIAT).

- Economic review of the pulses sector and pulses-related policies in Pakistan. In: Mid-Project Workshop of ACIAR Project ADP/2016/140 “How Can Policy Reform Remove Constraints and increase Productivity in Pakistan. Australian National University, University of Western Australia and PARC Islamabad; 2017. p. :1-170.

- [Google Scholar]

- Molds and Mycotoxins in Stored Products. K K-State Research and Extension, Kansas State University; 2012.

- Effect of aflatoxin B1 on development, survival and fecundity of Ahasverus advena (Waltl) J. Stored Prod. Res.. 2018;77:225-230.

- [Google Scholar]