Translate this page into:

Phytochemical analysis and antibacterial activity of Washingtonia filifera (Lindl.) H. Wendl. fruit extract from Saudi Arabia

⁎Corresponding author. nabutaha@ksu.edu.sa (Nael Abutaha), nabutaha@ksu.edu.sa (Fahd A. AL-mekhlafi)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

This work aimed to assess the antimicrobial potential of Washingtonia filifera extracts on some human pathogens. Agar well diffusion and minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) methods have been used to assess the antimicrobial activities of W. filifera extract against Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumonia, Acinetobacter baumannii, Escherichia coli, and Candida albicans. Only the ethyl acetate (ETAC) and methanol extracts revealed antimicrobial activity against tested microorganisms. S. aureus appears to be the most sensitive microbes to the ETAC extract with equal inhibition zone (30 mm) and MIC (65 µg/mL) values. This is followed by K. pneumoniae, E. coli, and A. baumanni, respectively. The plant extract had different phytochemical constituents such as alkaloids, sterols, and polyphenols. Column chromatography of the ETAC extract resulted in the loss of inhibitory effect at the highest concentration tested (50 mg/mL) against tested microorganisms. The haemolytic activity of the different extracts was found in the following order: Hexane (83.57%) > ETAC (35.71%) > chloroform (23.57143) > methanol (0.71%) based on the highest concentration tested (8.3 mg/mL). In conclusion, ETAC extract was the most promsing extract among extracts tested. Secondary plant metabolites are of great value as natural antimicrobial agents.

Keywords

Fan palm

Antimicrobial activity

Blood hemolysis

Secondary metabolites

1 Introduction

The emergence of multidrug-resistant microorganisms has negatively impacted the global effectiveness of antibiotics (D’Andrea et al., 2019; Falcone and Paterson, 2016; Algammal et al., 2023). As a result, it increases healthcare costs, mortality, and morbidity (Opperman and Nguyen, 2015). The condition is further worrying by the lack of efficient laboratory diagnostics, access to suitable antimicrobials, and surveillance systems in low-income countries. If there were no serious efforts to look for new antimicrobial agents, the health care costs, mortality, and morbidity would rise (Kebede et al., 2021; Morehead and Scarbrough, 2018; Raoult and Paul, 2016). To this effect, the search for novel antimicrobial agents from botanical sources to overcome the health and socio-economic burden caused by multidrug-resistant pathogens is necessary (Bakal et al., 2017; Solomon and Oliver, 2014; Aldhanhani et al., 2022a, 2022b).

Plants were used centuries ago to treat various conditions in different civilizations. Around 80% of the world's population are dependent on natural remedies to treat various ailments (Oyebode et al., 2016), and about 75% of approved drugs are isolated from natural sources (Cragg and Newman, 2013). Medicinal plants contain polypeptides, essential oils, tannins, terpenoids, alkaloids, polyphenols, flavonoids, and coumarins (Chandra et al., 2017; Aldhanhani et al., 2022a, 2022b). These secondary metabolites are used as a source for discovering antibiotics and treating various diseases (Cragg and Newman, 2013). The extract of Polysphaeria aethiopica, Euphorbia depauperata, Cirsium englerianum, Lippia adoensis, Cucumis pustulatus, Discopodium penninervium, and Rumex abyssinicus have antimicrobial activities against resistance and nonresistance microbes such as E. coli, S. aureus, K. pneumoniae, Streptococcus pyogenes, Trichophyton mentagrophytes, and Candida albicans (Kebede et al., 2021). In another study, the dichloromethane and ETAC extract of W. somnifera was active against Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), T. mentagrophytes, and Microsporum gypseum, but not active against C. albicans and Cryptococcus neoformans (Mwitari et al., 2013). The extracts of Thevetia peruviana, Erythrophleum suaveolens, and Euphorbia hirta, reported to possess antibacterial effects against E. coli, Pseudomonas, K. pneumonia, MRSA, Salmonella spp. and Proteus spp. (Niranjan et al., 2017; Sharifi-Rad et al., 2016).

It has been pointed out that natural products are significant sources of new bioactive compounds (Dar et al., 2017; Khalil et al., 2022). Botanical sources are valuable for novel bioactive secondary metabolites due to their ecological diversity and diverse chemical constituents (Kenneth-Obosi and Babayemi, 2017; Xylia et al., 2022).

W. filifera (family of Arecaceae) (Fig. 1) is commonly known as desert fan palm. W. filifera is the native palm of the Western United States (Uluçınar, 2017) and has been cultivated in the Mediterranean and elsewhere (El-Sayed et al., 2006) 2006). The fruits are creamy white, oval in shape, and around 13 cm in size (Watson, 1994). When they mature, their color changes to black, and the seeds (8 mm) are present inside the part of the fruits (Uluçınar, 2017). Yet, there are limited details of W. filifera antimicrobial potential and toxicity as therapeutic agents for standard and clinical microbes. Therefore, the present study aims to assess the antimicrobial activity, toxicity and phytochemical analysis of W. filifera fruit extracts using different solvents.

Washingtonia filifera tree (left) and its fruits (right) cultivated in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Riyadh.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Collection and authentication of W. Filifera

The unripen fruits of W. filifera (Fig. 1) were collected from the King Saud University campus in September 2021, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. A taxonomist identified the plant at the Department of Botany and Microbiology, King Saud University. The specimen (Voucher number BRC-040) was deposited in herbaria for future reference.

2.2 Preparation of extract

2.2.1 Soxhlet extraction

Sixty grams of the coarsely powdered fruit of W. filifera was Soxhlet extracted by sequential extraction in solvents of increasing polarity (hexane, chloroform, ETAC, and methanol). The extraction was carried out for 12 h or until colorless and then concentrated by Rotavapor at 45 °C.

2.2.2 Silica gel column chromatography.

Five grams of the ETAC extract were dissolved in ETAC, mixed with silica gel, and left until completely dried (1 mL). This mixture was loaded on a chromatographic glass column (4 cm, 30 cm height) packed with chloroform slurry of silica gel 60 silanized (Merk, Germany) previously activated (100 °C for 1 h). The column was eluted with toluene: chloroform (70:30), toluene: chloroform: methanol (7:2:1), toluene: chloroform: methanol (6:2:2), chloroform: methanol (3:7), and methanol (100%). Five fractions (400 mL each) were collected. Each fraction was evaporated by Rota vapor at 45 °C, and the stock solution was prepared (10 mg/mL).

2.3 Phytochemical screening

Phytochemical analysis was conducted on extracts and fractions derived from W. filifera. Identification tannin/phenol was assessed using Ferric Chloridés test, alkaloids using Dragendorff́s test, saponins by foam appearance, steroids/triterpenoids using Liebermann-Buchard́s test, sugars using thronés reagent, flavonoid by Shinodás test (HUI et al., 2018).

2.4 Test microorganisms

Clinical and standard isolates, including Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922), Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 25923), Klebsiella pneumonia ATCC (BAA-1705), Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC BAA-747, Staphylococcus aureus (clinical isolate), Acinetobacter baumannii (clinical isolate), and Candida albicans ATCC-66027 were collected from Microbiology Laboratory, King Saud University, Riyadh.

2.5 Inoculum preparation

All microbes were refreshed in Petri dishes containing nutrient agar or potato dextrose agar by incubation for 20 h at 37 °C. A loopful of grown bacteria was added to 5 mL of broth culture. The absorbance was adjusted at 600 nm and diluted to attain a cell count of 107 CFU/ml using a spectrophotometer (Obeidat et al., 2012).

2.6 Agar well diffusion assay

Agar well diffusion method was carried out as previously reported (Abutaha et al., 2021). The broth culture that was standardized in the preceding section was evenly applied onto Petri plates using a sterile cotton swab. Six milimeter wells were made with a cork borer. Twenty microliters of 10 mg/ml of each extract was pipetted into each well, making the final concentration 200 µg/well. DMSO was used as a negative control. The plates were kept for about 2 h at 25 °C. The plates were incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. A ruler was used to measure the inhibition zone. Each assay was carried out in three independent replicates, and the mean was calculated.

2.7 Determination of the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC)

The promising extracts were serially diluted using 96 well-plates (NEST, China). A volume of 100 μl of MHB was added to each well. The columns (A to E) were loaded with 50 μl stock solution (10 mg/ml) of the extract except for the last three rows in which equal amount of DMSO (F row), standard antibiotic (G row), and sterility control (50 μl of MHB) (H row) were added. A series of three-fold dilutions were carried out. Subsequently, bacterial suspension (100 μl) was added to the wells, with the exception of the 7th and 8th rows, which were designated for sterility control and color contrast control, respectively. Following the serial dilution, a resulting concentration range of 1.6 mg/mL to 0.0008 mg/mL was achieved. Ultimately, the plates were placed in an incubator at 37 °C for a duration of 24 h. The MIC value is determined as the minimum extract concentration where no turbidity was observed. All experiments were conducted in triplicate.

2.8 Hemolytic activity (HA)

The Hemolytic activity of all the extracts was investigated using human erythrocytes (hRBCs) following the method of a previous report (Abutaha et al., 2021). A 5% (v/v) suspension of erythrocytes was mixed with different extract concentrations in a 96-well plate at 37 °C for 30 min. Plates were pelleted by centrifuged for 3 min at 3,000 rpm. The supernatant was transferred to 96-well and used to calculate the released hemoglobin at 540 nm (ChroMate, England). Phosphate buffer saline was employed as the negative control, while Triton X-100 (1%) served as the positive control. Three separate experiments were conducted in duplicate, and the hemolysis percentage was calculated using the following equation.

2.9 Statistical analysis

The results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. The statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel, and the graphs were generated using OriginPro 8.5 software.

3 Result

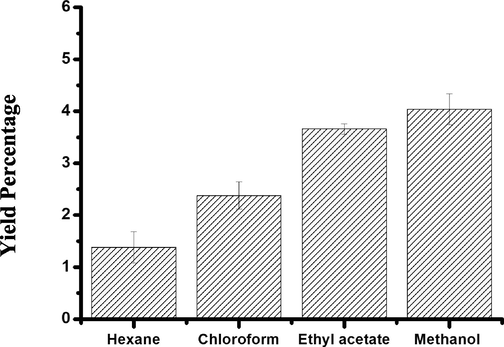

The tested plant extracts showed a variation in the percentage of yield. The methanol extract showed the highest yield at 6%, whereas the hexane extract displayed the lowest yield of 1.38% (Fig. 2). Chromatographic separation of ETAC extract was carried out and produced a total of 5 fractions. F3 and F2 fractions exhibited the highest yields at 40% and 35%, respectively. Conversely, the lowest yields were identified in F4 and F5 fractions at 3.2% and 2.5%, respectively. The phytochemical investigation of the separated fractions (Table 1) showed the presence of polyphenols and alkaloids in F3 and F4 fractions (Table 1). F2 and F3 gave only a faint coloration in alkaloid reactions. The remaining fractions failed to show the presence of any of these secondary metabolites tested. No antioxidant activity was observed in all the solvents and fractions obtained.

Yield obtained from extracting Washingtonia filifera in solvents of increasing polarity using soxhlet extractor. The values are expressed as mean ± SD of the three replicates.

Phytochemical Tests

Hexane

Chloroform

Ethyl acetate

Methanol

F1

F2

F3

F4

F5

Polyhenol

+

+

++

+

–

–

–

+++

+++

Alkaloid

–

–

+

+

–

+

++

+

Tannin

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

Sterols

–

–

–

+

–

–

–

–

–

Anthraquinone glycosides

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

Antioxidant

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

This work aims to assess the antimicrobial potential of hexane, chloroform, ETAC, and methanol extracts of W. filifera on some human pathogenic microorganisms. Agar well diffusion and minimum inhibitory concertation methods have been used to assess the antimicrobial potential of W. filifera extracts against S. aureus (Gram-positive bacteria), K. pneumoniae, E. coli, and A. baumanni (Gram-negative bacteria), and one fungus (C. albicans). Only the ETAC and methanol extracts exhibited antimicrobial activities against tested microorganisms. ETAC and methanol extracts showed antibacterial activity against tested bacterial strains and C. albicans. However, the ETAC extract was more effective against all tested organisms. S. aureus (ATCC-29213) and S. aureus (clinical) appear to be the most sensitive microbes to the ETAC extract with equal inhibition zone (30 µg/mL) and MIC (65 µg/mL) values. This is followed by K. pneumoniae, E. coli, A. baumanni (Clinical) and A. baumanni (ATCC - BAA-747) respectively (Table 2). The values are expressed as mean ± SD of the three replicates.

Microorganism

Origin

Resistance phenotype

Well assay zone (mm)

Ethyl acetate extract

MIC

(µg/mL)

Well assay zone (mm)

Methanol extract

MIC (µg/mL)

Microbes

K. pneumoniae

ATCC (BAA-1705)

S

20 ± 0.01

26

15 ± 0.6

520

E. coli

ATCC -25922

S

20 ± 0.09

26

17 ± 0.6

520

A. baumanni

ATCC - BAA-747

S

15 ± 0.6

26

10 ± 0.6

520

A. baumanni

Clinical

Amox/K, clav, amx, ampicillin, cxm,fix, cefpodoxime

16 ± 1.0

26

10 ± 1.0

520

S. aureus

Clinical

S

30 ± 0.6

6.5

30 ± 0.6

65

S. aureus

ATCC-29213

S

30 ± 0.6

6.5

25 ± 0.01

65

C.albican

ATCC- 66,027

S

8 ± 1.2

200

8 ± 0.9

200

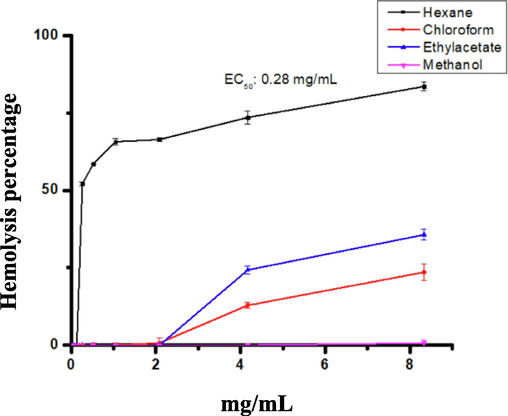

The haemolytic activity of the different solvent extracts of W. filifera fruit was screened against normal hRBCs. Haemolytic is reported as a percentage hemolysis of three experiments. ETAC and chloroform extracts exhibited very low haemolytic effects toward human erythrocytes, whereas hexane extract showed the maximum haemolytic activity and ranked first in the list. However, methanol extract showed no haemolytic activity towards normal hRBCs. These extracts showed an increase in haemolytic activity with the increasing concentration of the extracts (Fig. 3). The EC50 for chloroform, ETAC, and methanol extracts were not calculated because the hemolysis of the highest tested concentration (8.3 mg/mL) was less than 40%. Based on the highest concentration tested (8.3 mg/mL), the haemolytic activity of the different extracts was found in the following order: Hexane (83.57%) > ETAC (35.71%) > chloroform (23.57143) > methanol (0.71%). The IC50 value was calculated only for hexane extract (EC50:280 µg/mL); the hexane extract showed the maximum hemolytic activity and ranked first in the list.

Haemolytic activity was examined after incubation at 37 °C for 30 min using different solvent extracts of Washingtonia filifera fruits against human erythrocytes. The values are expressed as mean ± SD of the three replicates.

4 Discussion

WHO has recognized the rise of microbial antibiotic resistance as a global health risk that necessitates the attention of countries and organizations (van Duin and Doi, 2017). Therefore, there is a dire need to search for new antimicrobial agents from natural resources to overcome the rising threat of resistant pathogens. This study revealed that ETAC and methanol extracts had broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity. S. aureus (gram-positive) was the most susceptible bacteria of all tested pathogens. This finding agrees with several reports that gram-positive bacteria are more susceptible to botanical extracts than gram-negative ones (K. pneumonia, E. coli, and A. baumannii).

A. baumannii is a significant and challenging pathogen that has become a global concern. It causes a wide range of infections, particularly in immunocompromised individuals within intensive care units. A significant concern linked to this pathogen is its capacity to develop resistance to a vast majority of antibiotics that are employed in clinical practice (Elwakil et al., 2023).

The outbreaks of A. baumannii infections have been reported globally. At present, antibiotic choices to treat A. baumannii are limited due to multidrug-resistant (Perez et al., 2007), and current antimicrobial agents in the pharmaceutical pipeline do not appear promising (Karageorgopoulos and Falagas, 2008). To our knowledge, this is the first report of anti-A. baumannii activities of W. filifera extract, although weak inhibitory activities of W. filifera against other pathogenic bacteria, have been reported. For example, 70% methanol and ETAC extracts of mature and immature seeds were shown to inhibit S. aureus and E. coli (Uluçınar, 2017). This weak activity reported could be due to the methods of extraction adopted. On the other hand, other biological activities have also been reported. The alcoholic seed extracts of W. filifera showed inhibitory activity to xanthine oxidase, α-glucosidase, butyrylcholinesterase, α-amylase, elastase, and collagenase (Floris, 2021).

The mechanical stability of the hRBCs membrane is an excellent indicator to assess in vitro effects of secondary metabolites when screening for cytotoxicity (Baillie et al., 2009; Sharma and Sharma, 2001). Treating cells with toxic secondary metabolites may cause loss of membrane lipid bilayer integrity and death of cells due to cell lysis (Tiwari et al., 2011). The hemolytic activity of the W. filifera extracts (ETAC and methanol) gave a much higher range than that of the MIC values against all microorganisms tested.

In the present study, different bioactive compounds (alkaloids and polyphenolic compounds) extracted from W. filifera inhibited the growth of both clinical and reference isolates. Other reports have also documented that the plant extracts containing polyacetylenes, tannins, terpenoids, alkaloids, coumarins, polyphenols, and flavonoids which are promising antimicrobials against different human pathogens (Dholaria and Desai, 2018; Habtamu et al., 2010; Keita et al., 2022). This inhibitory effect of phytocompounds come from the disintegration of the outer membrane, disruption of the biochemical pathway, and inhibition of protein synthesis (Ellington et al., 2010; Shriram et al., 2018). Therefore, a lot has to be carried out to investigate the antimicrobial potential of plant extracts to treat human-resistant pathogens. On further fractionation, column chromatography of the ETAC extract resulted in the loss of inhibitory effect at the highest concentration tested (50 mg/mL) against all tested microorganisms. We hypothesized that the antimicrobial activity of W. filifera extract might have acted synergistically or additively to produce the activity observed with the parent fraction. This result is in agreement with the previously published papers (Nwodo et al., 2010).

5 Conclusion

The study revealed that the use of methanol and ETAC solvents in extracting W. filifera resulted in antibacterial activity, surpassing the effects of n-hexane and chloroform solvents. Notably, the ETAC extract exhibited potent antibacterial activity. Among the tested microorganisms, S. aureus demonstrated the highest sensitivity to the ETAC extract, showing equal inhibition zone (30 mm) and MIC (65 µg/mL) values. The ETAC and chloroform extracts displayed minimal toxicity towards human erythrocytes, while the hexane extract exhibited the highest level of haemolytic activity (EC50: 280 µg/mL). Further investigations on toxicity are needed to uncover the potential of W. filifera extract as an effective antibacterial agent.

Acknowledgement

Researchers Supporting Project number (RSPD2023R757), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Potency and selectivity indices of Myristica fragrans Houtt. mace chloroform extract against non-clinical and clinical human pathogens. Open Chem.. 2021;19(1):1096-1107.

- [Google Scholar]

- Maturity stage at harvest influences antioxidant phytochemicals and antibacterial activity of jujube fruit (Ziziphus mauritiana Lamk. and Ziziphus spina-christi L.) Ann. Agric. Sci.. 2022;67(2):196-203.

- [Google Scholar]

- Aldhanhani, A., Kaur, N., Ahmed, Z., 2022. Antioxidant phytochemicals and antibacterial activities of sidr (Ziziphus spp.) leaf extracts. In: XXXI International Horticultural Congress (IHC2022): International Symposium on Integrative Approaches to Product Quality in 1353.

- Emerging multidrug-resistant bacterial pathogens “superbugs”: A rising public health threat. Front. Microbiol.. 2023;14:1135614.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Oral antioxidant supplementation does not prevent acute mountain sickness: double blind, randomized placebo-controlled trial. QJM: An Int. J. Med.. 2009;102(5):341-348.

- [Google Scholar]

- Finding novel antibiotic substances from medicinal plants—antimicrobial properties of Nigella sativa directed against multidrug resistant bacteria. Eur. J. Microbiol. Immunol.. 2017;7(1):92-98.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial resistance and the alternative resources with special emphasis on plant-based antimicrobials—a review. Plants. 2017;6(2):16.

- [Google Scholar]

- Natural products: a continuing source of novel drug leads. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-General Subjects. 2013;1830(6):3670-3695.

- [Google Scholar]

- The urgent need for novel antimicrobial agents and strategies to fight antibiotic resistance. Multidisc. Digital Publishing Inst.. 2019;8(4):254. (PMID: 31817707; PMCID: PMC6963704)

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- General overview of medicinal plants: a review. J. Phytopharmacol.. 2017;6(6):349-351.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antibacterial and phytochemical studies with cytotoxicity assay of Kalanchoe pinnata leave extract against multi-drug resistant human pathogens isolated from UTI. J. Emerg. Technol. Innov. Res.. 2018;5(12):581-589.

- [Google Scholar]

- Polyclonal multiply antibiotic-resistant methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus with Panton-Valentine leucocidin in England. J. Antimicrob. Chemother.. 2010;65(1):46-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antioxidant activity and two new flavonoids from Washingtonia filifera. Nat. Prod. Res.. 2006;20(1):57-61.

- [Google Scholar]

- Multidrug-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Infections in the United Kingdom versus Egypt: trends and potential natural products solutions. Antibiotics. 2023;12(1):77.

- [Google Scholar]

- Spotlight on ceftazidime/avibactam: a new option for MDR Gram-negative infections. J. Antimicrob. Chemother.. 2016;71(10):2713-2722.

- [Google Scholar]

- Floris, S., 2021. Biological activities and phenolic composition of washingtonia filifera seeds [Phd]. https://iris.unica.it/handle/11584/313227. Accessed 15-6-2023.

- In vitro antimicrobial activity of selected Ethiopian medicinal plants against some bacteria of veterinary importance. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res.. 2010;4(12):1230-1234.

- [Google Scholar]

- Preliminary phytochemical screening and effect of hot water extraction conditions on phenolic contents and antioxidant capacities of Morinda citrifolia leaf. Malays. Appl. Biol.. 2018;47(4):13-24.

- [Google Scholar]

- Current control and treatment of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii infections. Lancet Infect. Dis.. 2008;8(12):751-762.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial activities evaluation and phytochemical screening of some selected medicinal plants: a possible alternative in the treatment of multidrug-resistant microbes. PLoS One. 2021;16(3):e0249253.

- [Google Scholar]

- Secondary plant metabolites as potent drug candidates against antimicrobial-resistant pathogens. SN Appl. Sci.. 2022;4(8):209.

- [Google Scholar]

- Qualitative and quantitative evaluation of phytochemical constituents of selected horticultural and medicinal plants in Nigeria. Int. J. Homeopath Nat. Med.. 2017;3(1):1.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mitigation of salinity stress on pomegranate (Punica granatum L. cv. Wonderful) plant using salicylic acid foliar spray. Horticulturae.. 2022;8(5):375.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial activity and probable mechanisms of action of medicinal plants of Kenya: Withania somnifera, Warbugia ugandensis, Prunus africana and Plectrunthus barbatus. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e65619.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pharmacological investigation of leaves of polypodium decumanum for antidiabetic activity. J. Drug Deliv. Ther.. 2017;7(4):69-72.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of fractionation on antibacterial activity of crude extracts of Tamarindus indica. Afr. J. Biotechnol.. 2010;9(42):7108-7113.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial activity of crude extracts of some plant leaves. Res. J. Microbiol.. 2012;7(1):59-67.

- [Google Scholar]

- Recent advances toward a molecular mechanism of efflux pump inhibition. Front. Microbiol.. 2015;6:421.

- [Google Scholar]

- Use of traditional medicine in middle-income countries: a WHO-SAGE study. Health Policy Plan.. 2016;31(8):984-991.

- [Google Scholar]

- Global challenge of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.. 2007;51(10):3471-3484.

- [Google Scholar]

- Is there a terrible issue with bacterial resistance: pro–con. Clin. Microbiol. Infect.. 2016;22(5):403-404.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antibacterial activities of essential oils from Iranian medicinal plants on extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli. Cell. Mol. Biol.. 2016;62(9):75-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- In vitro hemolysis of human erythrocytes—by plant extracts with antiplasmodial activity. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 2001;74(3):239-243.

- [Google Scholar]

- Inhibiting bacterial drug efflux pumps via phyto-therapeutics to combat threatening antimicrobial resistance. Front. Microbiol.. 2018;9:2990.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States: stepping back from the brink. Am. Fam. Physician. 2014;89(12):938-941.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phytochemical screening and extraction: a review. Internationale pharmaceutica sciencia. 2011;1(1):98-106.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phytochemical Analysis and Biochemical Analysis of Washingtonia filifera Fruits and Seeds. Eastern Mediterranean University (EMU)-Doğu Akdeniz Üniversitesi (DAÜ); 2017.

- van Duin, D., Doi, Y., The global epidemiology of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Virulence 2017; 8 (4): 460-9. PubMed Abstract| Publisher Full Text| Free Full Text.

- Watson, E.F.G.a.D.G., 1994. Washingtonia filifera Desert Palm. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/ST669 (Date of access 1\3\2023).

- Application of rosemary and eucalyptus essential oils on the preservation of cucumber fruit. Horticulturae. 2022;8(9):774.

- [Google Scholar]

Appendix A

Supplementary material

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2023.102899.

Appendix A

Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article: