Translate this page into:

Laboratory evaluation of selected botanicals and insecticides against invasive Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae)

⁎Corresponding author at: Guangdong Key Laboratory of Animal Conservation and Resource Utilization, Guangdong Public Laboratory of Wild Animal Conservation and Utilization, Institute of Zoology, Guangdong Academy of Sciences, Guangzhou 510260, China. junl@giabr.gd.cn (Jun Li)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Background

Maize is an economical crop of China, and its production has been severely affected by the invasive Spodoptera frugiperda in recent year. Application of synthetic pesticides are one of the most effective practices against FAW as an emergency control. This pest causes serious damage to the maize crop worldwide in recent decade, especially in China.

Methods

To find an alternative to synthetic insecticides there were total 16 different chemicals were used including ten botanical insecticides comprising of seven botanicals, azadirachtin, pyrethrin, nicotine, osthole, rotenone, Celastrus angulatus, matrine, and three insect growth regulators, diflubenzuron, lufenuron and buprofezin. Six synthetic insecticides, including emamectin benzoate, indoxacarb, imidacloprid and thiamethoxan, chlorantraniliprole, chlorfenapyr, were evaluated against 2nd instar of S. frugiperda larvae using leaf-dip method.

Results

The results revealed that osthole, azadirachtin, buprofezin and pyrethrin were showed the significant larval mortality of 98.0, 96.7, 94.0 and 90.7%, in 120 h observation and exhibiting minimum LC50 (39.04, 35.58, 61.45 and 48.46 mg/L, respectively) and LT50 (48.91, 68.85, 58.67 and 58.57 h, respectively) values. Among tested synthetic insecticides, emamectin benzoate, chlorantraniliprole and chlorfenapyr were showed significant higher mortality against larvae of S. frugiperda (99.3, 96.0 and 89.3%, respectively) in 72 h observation by exhibiting minimum LC50 (0.26, 0.39 and 0.72 mg/L, respectively) and and LT50 (10.18, 10.57 and 13.42 h, respectively) values. More study is needed to test the laboratory findings in the field, although the efficient biorational pesticides might be utilized as part of integrated pest management against S. frugiperda.

Conclusion

The effective chemicals could be used in the management for S. frugiperda. The highest discriminating concentrations of tested botanical insecticides, insect growth regulators and insecticides caused significant mortality of S. frugiperda larvae.

Keywords

Maize

Spodoptera frugiperda

Botanical insecticides

Instar

Larval mortality

1 Introduction

The United States is the leading producer and consumer of maize, but China has quickly overtaken them (Wu et al., 2021). Spodoptera frugiperda, fall armyworm (FAW) is native to the Americas and extremely prolific, polyphagous pest of more than 350 different plant species especially of maize (Navik et al., 2021). S. frugiperda has expanded throughout the world, with first detection in Africa, Nepal, Indonesia, and Swaziland (Acharya et al., 2020). The production of horticultural crop is severely threatened due to attack of FAW, which has been found in cereals and vegetables around the world (Yeboah et al., 2021).

One survey predicts that by 2019, FAW would cause annual financial losses of US$2.5–6.2 billion in maize across 44 African nations (Bengyella et al., 2021). Hence, FAW is classified as an A1 quarantine invasive pest (Kasoma et al., 2020). The S. frugiperda caused major yield losses of maize in Ethiopia and Kenya and most of the maize growers preferred to use pesticides for controlling this pest (Susanto et al., 2021a). On December 11th, 2018, the FAW corn strain was first identified in China (Guo et al., 2018), damaging maize, in Yunnan province, China, and afterwards invaded 26 provinces (Jing et al., 2020). At the seedling and flowering phases, FAW larvae caused 78 and 65% of the damage in peanut fields (Yang X et al., 2019), 30 to 90% of the damage in wheat fields (Yang et al., 2020). When the population of FAW is very high, it may also cause harm to tobacco crops (Xu et al., 2019).

The creation of integrated pest management is only one example of the many environmentally friendly methods of pest management that have been the subject of studies across the world (Idrees et al., 2021, 2017; Qadir et al., 2021). Although the control of these insect pests with insecticides remains until today the most serious concern. However, it is often ineffective, and the frequent misuse of these insecticides has led to the emergence of insect resistance to several classes of insecticides (Goergen et al., 2016). The selected botanical insecticides, insect growth regulators and novel insecticides might play a significant role in the management of FAW.

In order to determine the most effective botanicals and synthetic insecticides that may be advised against FAW, the current study was done to evaluate the effectiveness of various botanical and synthetic insecticides against 2nd instar larvae of FAW under laboratory circumstances.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Insects

During the growing season for maize in Guangdong province, China, larvae were collected and used to construct a colony of S. frugiperda. Adults were artificially fed a 10% honey solution soaked in sterile cotton balls while the captured larvae were raised on fresh maize leaves. Neonates of S. frugiperda were transferred to a box (28 × 17 × 18 cm) from a development chamber maintained at 25 ± 2 °C, with a photoperiod of 16:8h (L: D), and 65% 5% R.H. All the experiment was conducted at Institute of Zoology, Guangdong Academy of Sciences. A colony of larvae was maintained for one hundred generations in an artificial indoor environment.

2.2 Botanical and synthetic insecticidal treatments

We put ten widely used botanicals and six widely available synthetic insecticides from five chemical classes through their paces against 2nd instar S. frugiperda. You may find the formulation type and supplier details at (Table 1). WP: wettable powder; LC:liquid concentrations; WG: water soluble granule; SC: suspension concentrate; ME: microemulsion; EC: emulsifiable concentrate.

Active Ingredients

Formulation

Chemical Group

Source

Manufacturer

Botanicals

Azadirachtin

25% WP

Limonoid Group

Neem tree

Dow AgroSciences

Pyrethrin

70% WP

Organic Compounds

Chrysanthemum flowers

Dow AgroSciences

Nicotine

1% LC

Alkaloid

Tobacco Plant

Jiangsu Yangnong Chemicals

Matrine

40% WP

Alkaloid

Sophora flavescens Aiton

Yangjiang Company

Osthole

0.1% LC

Coumarin Compound

Cnidium monnieri

Beijing Kefa Weiye Chemicals

Rotenone

2% LC

Rotenones

Common Mullein

Syngenta

C. angulatus

99% WP

Sesquiterpene polyol esters

Root bark of C. angulatus

Chengdu Newsun Crop Science Co., Ltd.

Diflubenzuron

0.1 LC

Insect growth regulators

Syngenta

Lufenuron

25% WG

IGRs

Syngenta

Buprofezin

25% WP

IGRs

Syngenta

Synthetic Insecticides

Emamectin benzoate

5% ME

6A, Avermectins

Hebei Weiyuan Company

Indoxacarb

150 EC

22A, Oxadiazines

Hebei Weiyuan Company

Imidacloprid

600 SC

4A, neonicotinoids

Hebei Weiyuan Company

Thiamethoxam

25% WG

Chlorantraniliprole

5% SC

28A, Diamides

DuPont, USA

Chlorfenapyr

30% EC

13A, Pyrroles

Fuyang Chemicals

2.3 Toxicity bioassays with botanical and synthetic insecticides

The typical leaf-dip approach was used to carry out the experiment. In contrast to first instar larvae, which are fragile and sensitive and susceptible to mechanical harm when handled, second instar larvae are utilized because they are simpler to handle or manipulate. For each botanical and synthetic insecticides, five different concentrations were prepared in distilled water by serial dilution from a stock solution i.e., (C1-C5) 400, 200, 100, 50, 25 mg/L and (3.125, 6.25, 12.5, 25.0, 50.0 mg/L), respectively. Three newly made discs of maize leaves were put in a Petri dish after being dipped into a solution containing natural and synthetic pesticides. Each Petri plate contained thirty S. frugiperda 2nd instar larvae that had been pre-starved for four hours. All bioassays were conducted and maintained chamber at 25 ± 2 °C, with a photoperiod of 16 h:8h (L: D) and 65% ± 5% RH. Larval mortality was recorded 24, 48, 72, 96 and 120 h post-treatment for botanicals while 24, 48 and 72 h post-treatment for synthetic insecticides. Larvae were regarded alive if they moved in response to the gentle brushing of a camel's hair, and dead if they did not respond. A total of 150 larvae (five replicate/30 larvae in each) were used in each treatment. Fresh leaves treated with distilled water was used in the control treatment. Toxicity Index = LC50 of the most effective compound/LC50 of the other tested compound × 100

2.4 Statistical analysis

The POLO Plus program was used to examine the bioassay results (Robertson et al., 1980), determine the median lethal concentrations (LC50), 95% confidence limits (CLs), slope, standard error, and chi-squared (χ2) test. The SPSS statistics software was used to determine the degree of freedom (df) and p value. Data on larval mortality were analyzed using factorial analysis of variance (ANOVA), with mortality rates corrected using the Abbott technique (Abbott, 1925), and the treatment means compared using Tukey's highly significant difference (HSD) post-hoc test at the 95% level of significance. Two LT50 values were considered to be statistically distinct if their 95% confidence intervals did not overlap (Litchfield and Wilcoxon, 1949). The percentages of larval mortality for each treatment were transformed using an arcsine function to lessen the amount of variability in the data (Freeman et al., 1985). In contrast to factorial analysis of variance, which was used to calculate mortality data, one way analysis of variance was used to compute mortality data.

3 Results

3.1 Comparative toxicity of botanicals against S. frugiperda larvae

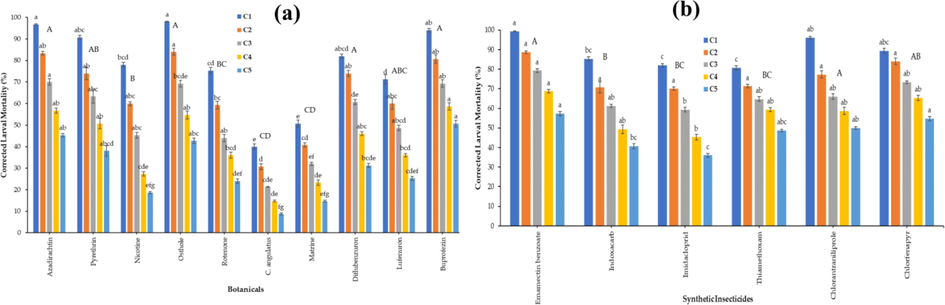

Factorial analysis revealed that osthole, azadirachtin and buprofezin showed the highest larval mortality of 98.0, 96.7 and 94.0% respectively, followed by pyrethrin (90.7%) and diflubenzuron (82.0%). Lowest larval mortality was observed in matrine (50.7%) and C. angulatus (40.0%) treated with highest concentration 1 (F10 = 57.06, p < 0.000) at 120 h after application (Fig. 1a).

Percent mortality (mean ± S.E.) of 2nd instar larvae of S. frugiperda against different Concentrations C1 – C5 were 400 to 25 mg/L of botanical insecticides (a) and synthetic insecticides (b). The small letters at bar tops indicate significant difference among concentrations, while capital letters indicate overall significant difference among the botanical insecticides (factorial ANOVA; HSD post-hoc test at α = 0.05).

Azadirachtin was the most toxic botanical exhibiting minimum LC50 value (575.69 mg/L) followed by nicotine (1059.23 mg/L) and pyrethrin (1271.14 mg/L) against 2nd instar larvae of S. frugiperda mortality at 24 h post-treatment. Matrine and C. angulatus were found to be least effective with maximum LC50 values (Table 2). Azadirachtin, osthole and pyrethrin outperformed among all tested botanicals by 604.88, 682.86 and 761.60 mg/L followed by the diflubenzuron (1030.36 mg/L) and buprofezin (1149.38 mg/L). The rotenone (1193.26 mg/L) and matrine (1301.41 mg/L) against 2nd instar larvae of S. frugiperda at 48 h after application of treatment (Table 2). SE, χ2, df, CL and mg/L indicate standard error, chi-square, degrees of freedom, confidence limits and milligrams per liter, respectively. When the 95% confidence intervals for two or more LC50 values for the same set of tested plants do not overlap (P 0.05), the results are statistically different.

24 h post-treatment

Botanical

Insecticides

Slope ± SE

χ2

(df = 3)

P value

LC50 (95% CL) (mg/L)

Reg. equation

(

)

Toxicity

index

Azadirachtin

1.31 ± 0.23

0.34

0.95

575.69 (292.30–2202.54)a

−3.53 + 1.26 x

100.00

Pyrethrin

0.97 ± 0.20

0.13

0.99

1271.14 (455.75–13102.88)bc

−2.98 + 0.95 x

45.29

Nicotine

1.18 ± 0.25

0.97

0.81

1059.23 (405.30–10643.33)ab

−3.36 + 1.06 x

54.35

Osthole

0.10 ± 0.19

0.00

1.00

4235.25 (1645.81–33278.17)cd

−3.61 + 1.00 x

13.59

Rotenone

1.02 ± 0.25

1.63

0.65

8092.34 (223.10–315354.49)fgh

−3.69 + 0.90 x

7.11

C. angulatus

1.16 ± 0.33

0.41

0.94

8380.47 (2122.56–1018209.58)ghi

−4.26 + 1.04 x

6.87

Matrine

0.98 ± 0.24

0.02

0.10

8888.55 (2378.67–357704.09)ghij

−3.85 + 0.97 x

6.48

Diflubenzuron

1.11 ± 0.23

0.09

0.99

4752.70 (1747.74–50637.02)de

−4.02 + 1.08 x

12.11

Lufenuron

1.10 ± 0.28

0.95

0.81

7560.38 (2126.55–321239.07)fg

−3.81 + 0.91 x

7.61

Buprofezin

0.10 ± 0.20

0.33

0.95

4905.20 (1791.36–47763.10)ef

−3.57 + 0.95 x

11.74

48 h post-treatment

Azadirachtin

1.40 ± 0.15

0.54

0.91

604.88 (449.37–929.37)a

−3.79 + 1.35 x

100.00

Pyrethrin

1.46 ± 0.17

0.53

0.91

761.60 (546.98–1252.72)bc

−4.09 + 1.40 x

79.42

Nicotine

0.91 ± 0.16

0.11

0.99

2898.64 (1281.38–14740.52)ghi

−3.11 + 0.89 x

20.87

Osthole

1.25 ± 0.14

4.51

0.21

682.86 (484.26–1141.10)ab

−3.38 + 1.18 x

88.58

Rotenone

1.16 ± 0.16

0.03

0.10

1193.26 (734.86–2669.80)def

−3.56 + 1.15 x

50.69

C. angulatus

1.07 ± 0.21

0.29

0.96

4095.46 (1614.28–32331.87)ghij

−4.01 + 1.14 x

14.77

Matrine

1.15 ± 0.16

0.25

0.97

1301.41 (782.49–3067.78)ef

−3.53 + 1.12 x

46.48

Diflubenzuron

1.24 ± 0.16

0.10

0.99

1030.36 (667.54–2074.74)cd

−3.79 + 1.26 x

58.71

Lufenuron

1.16 ± 0.17

0.12

0.99

1370.84 (813.54–3340.54)fgh

−3.69 + 1.18 x

44.12

Buprofezin

1.22 ± 0.16

0.46

0.93

1149.38 (723.24–2457.42)de

−3.64 + 1.18 x

52.62

72 h post-treatment

Azadirachtin

1.49 ± 0.13

1.68

0.64

199.19 (169.20–241.37)ab

−3.37 + 1.47 x

90.00

Pyrethrin

1.42 ± 0.14

0.21

0.98

390.61 (310.28–532.07)def

−3.67 + 1.41 x

45.90

Nicotine

1.13 ± 0.14

1.28

0.73

730.15 (498.57–1314.08)fgh

−3.14 + 1.09 x

24.55

Osthole

1.05 ± 0.12

1.01

0.80

179.28 (144.58–233.57)a

−2.36 + 1.05 x

100.00

Rotenone

1.35 ± 0.13

0.94

0.82

351.14 (279.51–475.87)cd

−3.38 + 1.32 x

51.06

C. angulatus

1.08 ± 0.18

0.18

0.98

2457.27 (1193.70–9902.21)ghij

−3.74 + 1.12 x

7.30

Matrine

1.12 ± 0.14

0.32

0.96

825.65 (547.91–1576.44)fghi

−3.26 + 1.12 x

21.71

Diflubenzuron

1.19 ± 0.13

0.46

0.93

328.97 (257.39–459.06)c

−3.02 + 1.20x

54.50

Lufenuron

1.24 ± 0.13

0.89

0.83

456.57 (345.70–676.70)efg

−3.37 + 1.27 x

39.27

Buprofezin

0.97 ± 0.12

0.02

0.10

360.94 (266.04–563.88)cde

−2.47 + 0.97 x

49.67

The osthole and azadirachtin showed LC50 values 179.28 and 199.19 mg/L, followed by diflubenzuron (328.97 mg/L) and rotenone (351.14 mg/L) against 2nd instar larvae of S. frugiperda. The buprofezin and pyrethrin showed LC50 values 360.54 and 390.61 mg/L, respectively, at 72 h after application (Table 2).

The azadirachtin and osthole showed LC50 values 63.50 and 66.31 mg/L, respectively, followed by pyrethrin (83.39 mg/L) against 2nd instar larvae of S. frugiperda. The buprofezin and diflubenzuron showed LC50 values 84.63 and 142.33 mg/L respectively, at 96 h after application (Table 3). SE, χ2, df, CL and mg/L indicate standard error, chi-square, degrees of freedom, confidence limits and milligrams per liter, respectively. When the 95% confidence intervals for two or more LC50 values for the same set of tested plants do not overlap (P 0.05), the results are statistically different.

96 h post-treatment

Botanical insecticides

Slope ± SE

χ2

(df = 3)

P value

LC50 (95% CL)

(mg/L)

Reg. equation

(

)

Toxicity Index

Azadirachtin

1.44 ± 0.12

3.29

0.35

63.50 (53.21–74.34)a

−2.66 + 1.48 x

100.00

Pyrethrin

1.03 ± 0.11

0.81

0.85

83.39 (66.77–102.59)abc

−2.00 + 1.04 x

76.15

Nicotine

1.27 ± 0.12

0.75

0.86

271.70 (219.89–356.95)fg

−3.06 + 1.26 x

23.37

Osthole

1.47 ± 0.12

4.03

0.26

66.31 (55.96–77.31)ab

−2.75 + 1.51 x

95.33

Rotenone

1.20 ± 0.12

0.30

0.96

201.62 (165.39–257.30)ef

−2.77 + 1.20 x

31.49

C. angulatus

1.01 ± 0.14

0.22

0.97

1103.67 (666.27–2577.13)hi

−3.05 + 1.00 x

5.75

Matrine

0.85 ± 0.12

0.69

0.87

720.18 (452.04–1579.29)h

−2.47 + 0.87 x

8.82

Diflubenzuron

1.15 ± 0.12

0.01

1.00

142.33 (117.83–176.10)e

−2.48 + 1.15x

44.61

Lufenuron

1.07 ± 0.11

0.38

0.94

218.04 (173.95–291.70)efg

−2.52 + 1.08 x

29.12

Buprofezin

1.27 ± 0.12

1.30

0.73

84.63 (70.65–100.46)bcd

−2.44 + 1.27 x

75.03

120 h post-treatment

Azadirachtin

1.42 ± 0.13

5.74

0.12

35.58 (27.75–43.19)ab

−2.45 + 1.56 x

82.77

Pyrethrin

1.24 ± 0.12

3.28

0.35

48.46 (38.21–58.80)bcd

−2.17 + 1.29 x

60.77

Nicotine

1.39 ± 0.12

1.09

0.78

122.16 (104.29–144.42)

−2.89 + 1.39 x

24.11

Osthole

1.56 ± 0.14

7.81

0.05

39.04 (31.60–46.37)abc

−2.86 + 1.78 x

75.44

Rotenone

1.12 ± 0.11

1.53

0.67

113.67 (93.72–139.19)fg

−2.30 + 1.12 x

25.91

C. angulatus

0.91 ± 0.13

0.06

0.10

738.48 (472.03–1542.41)hi

−2.63 + 0.92 x

3.99

Matrine

0.87 ± 0.12

0.21

0.98

369.95 (263.57–621.75)h

−2.24 + 0.87 x

7.96

Diflubenzuron

1.18 ± 0.12

0.36

0.95

61.45 (49.28–74.23)cde

−2.11 + 1.18x

47.93

Lufenuron

1.02 ± 0.11

0.02

0.10

111.38 (90.16–138.91)f

−2.09 + 1.02 x

26.44

Buprofezin

1.15 ± 0.13

4.10

0.17

29.45 (20.70–38.03)a

−1.84 + 1.24 x

100.00

The buprofezin, azadirachtin and osthole exhibited 29.45, 35.58 and 39.04 mg/L, respectively, followed by pyrethrin (48.46 mg/L) against 2nd instar larvae of S. frugiperda. The diflubenzuron showed LC50 value 61.45 mg/L respectively, followed by lufenuron (111.38 mg/L) (Table 3).

Probit regression analysis revealed that LT50 values were time dependent and independent of concentration for all tested botanicals for causing mortality against 2nd instar larvae of S. frugiperda. The buprofezin and azadirachtin were fast acting botanical with maximum LT50 values of 129.36 h (97.93–753.96) and 130.38 h (119.26–147.60), respectively, followed by osthole 138.06 h (123.12–162.49), pyrethrin 144.62 h (136.45–160.20) and diflubenzuron 169.57 h (145.68–216.90) against 2nd instar S. frugiperda while other botanicals were exhibiting LT50 values of 181.31 (153.08–244.72) to 385.72 h (244.00–1122.95) treated with the lowest concentration 1 (25 mg/L).

Azadirachtin and osthole were exhibiting minimum LT50 values of 48.40 h (36.19–59.95) and 48.91 h (35.32–61.72), respectively, followed by pyrethrin 58.57 h (41.64–77.33), buprofezin 58.67 h (35.96–84.90) and diflubenzuron 65.17 (60.39–70.24) against 2nd instar S. frugiperda while other botanical insecticides were exhibiting minimum LT50 values of 70.03 (64.93–75.59) to 171.52 h (139.88–236.49) (Table 4). SE, χ2, df, CL and mg/L indicate standard error, chi-square, degrees of freedom, confidence limits and milligrams per liter, respectively.

Fit of probe line

Botanicals

Concentrations

(mg/L)

Slope ± SE

χ2

(df = 3)

P

value

LT50 (95% CL)

(hours)

Reg. equation

(

)

Azadirachtin25

4.17 ± 0.45

6.08

0.10

130.38 (119.26–147.60)

−7.34 + 3.4 x

50

4.03 ± 0.37

6.24

0.10

103.82 (97.00–112.63)

−7.16 + 3.46 x

100

3.68 ± 0.29

10.07

0.01

88.65 (72.96–116.09)

−6.54 + 3.35 x

200

3.65 ± 0.26

5.66

0.12

68.85 (64.50–73.45)

−6.42 + 3.51 x

400

3.88 ± 0.25

12.69

0.00

48.40 (36.19–59.95)

−6.72 + 4.02 x

Pyrethrin25

3.92 ± 0.45

31.48

0.00

144.62 (136.45–160.20)

−6.5 + 2.87 x

50

3.69 ± 0.36

30.64

0.00

123.77 (85.79–140.50)

−6.26 + 2.91 x

100

3.45 ± 0.30

21.70

0.00

102.15 (74.97–253.36)

−6.06 + 2.99 x

200

3.14 ± 0.25

13.75

0.00

82.03 (62.94–119.01)

−5.64 + 2.95 x

400

3.27 ± 0.23

15.52

0.00

58.57 (41.64–77.33)

−5.77 + 3.29 x

Nicotine25

2.69 ± 0.49

1.39

0.71

264.41 (194.72–493.97)

−5.79 + 2.32 x

50

2.40 ± 0.36

1.57

0.67

230.31 (178.44–361.53)

−5.32 + 2.22 x

100

2.63 ± 0.30

7.43

0.05

152.69 (131.64–189.81)

−5.17 + 2.33 x

200

2.70 ± 0.26

7.57

0.05

110.20 (99.55–125.45)

−5.14 + 2.50 x

400

2.94 ± 0.23

10.95

0.01

77.29 (60.20–105.81)

−5.30 + 2.81 x

Osthole25

3.25 ± 0.36

2.26

0.52

138.06 (123.12–162.49)

−6.47 + 2.99 x

50

3.22 ± 0.30

2.85

0.41

111.25 (101.89–124.34)

−6.22 + 3.02 x

100

3.33 ± 0.27

6.39

0.09

88.68 (82.52–96.10)

−6.06 + 3.11 x

200

3.64 ± 0.25

14.51

0.00

68.08 (52.06–88.25)

−6.30 + 3.45 x

400

3.98 ± 0.25

15.48

0.00

48.91 (35.32–61.72)

−7.13 + 4.26 x

Rotenone25

3.30 ± 0.52

0.79

0.85

200.68 (163.53–291.52)

−7.08 + 3.04 x

50

2.91 ± 0.36

1.21

0.75

164.74 (140.98–20.9.41)

−5.97 + 2.66 x

100

2.55 ± 0.28

0.83

0.84

139.07 (121.39–168.75)

−5.27 + 2.45 x

200

2.65 ± 0.25

0.75

0.86

99.85 (90.82–112.14)

−5.18 + 2.59 x

400

3.01 ± 0.23

1.27

0.74

70.03 (64.93–75.59)

−5.57 + 3.02 x

C. angulatus

25

3.19 ± 0.85

0.61

0.89

319.25 (208.68–1208.91)

−7.48 + 2.93 x

50

2.34 ± 0.50

2.14

0.54

366.07 (236.21–1031.22)

−5.26 + 1.95 x

100

2.14 ± 0.37

1.14

0.77

297.33 (210.33–586.20)

−5.00 + 1.98 x

200

1.20 ± 0.29

2.34

0.50

229.75 (175.55–366.00)

−4.47 + 1.87 x

400

1.94 ± 0.25

2.13

0.55

171.52 (139.88–236.49)

−4.18 + 1.86 x

Matrine

25

2.16 ± 0.45

0.63

0.89

385.72 (244.00–1122.95)

−5.26 + 1.98 x

50

2.25 ± 0.36

1.48

0.69

258.14 (192.15–445.55)

−5.17 + 2.11 x

100

2.09 ± 0.30

0.38

0.95

209.12 (164.44–313.10)

−4.77 + 2.05 x

200

1.90 ± 0.25

0.31

0.96

161.22 (132.60–218.77)

−4.25 + 1.93 x

400

1.75 ± 0.22

2.43

0.49

118.97 (101.63–149.30)

−3.75 + 1.81 x

Diflubenzuron

25

3.50 ± 0.47

3.31

0.35

169.57 (145.68–216.90)

−6.65 + 2.90 x

50

3.42 ± 0.37

2.91

0.41

134.29 (120.75–155.85)

−6.51 + 3.02 x

100

3.24 ± 0.29

3.80

0.28

105.69 (97.24–117.10)

6.09 + 3.00 x

200

3.24 ± 0.26

3.58

0.31

82.53 (76.80–89.22)

−5.94 + 3.10 x

400

3.04 ± 0.23

3.71

0.30

65.17 (60.39–70.24)

−5.40 + 2.99 x

Lufenuron

25

3.80 ± 0.58

0.73

0.87

181.31 (153.08–244.72)

−8.06 + 3.53 x

50

3.06 ± 0.38

3.45

0.33

162.68 (140.15–204.51)

−6.02 + 2.67 x

100

3.06 ± 0.31

0.58

0.90

124.21 (111.93–142.88)

−6.14 + 2.92 x

200

2.91 ± 0.26

0.12

0.99

98.98 (90.78–109.87)

−5.74 + 2.88 x

400

2.85 ± 0.24

0.39

0.94

78.10 (72.15–85.03)

−5.32 + 2.81 x

Buprofezin

25

4.04 ± 0.42

17.83

0.00

129.36 (97.93–753.96)

−6.84 + 3.15 x

50

3.68 ± 0.35

16.45

0.00

115.58 (88.59–281.17)

−6.44 + 3.07 x

100

3.82 ± 0.30

15.17

0.00

92.20 (72.82–135.82)

−6.64 + 3.37 x

200

3.53 ± 0.26

15.38

0.00

75.38 (57.62–102.61)

−6.18 + 3.30 x

400

3.55 ± 0.24

26.89

0.00

58.67 (35.96–84.90)

−6.31 + 3.61 x

3.2 Toxicity of insecticides against 2nd instar larvae of S. frugiperda

Factorial analysis revealed that emamectin benzoate, chlorantraniliprole and chlorfenapyr were showed the highest larval mortality of 99.3, 96.0 and 89.3% respectively, followed by indoxacarb (85.3%) treated with highest concentration 1 (F6 = 132.38, p < 0.000) at 72 h post-treatment. emamectin benzoate, chlorantraniliprole and chlorfenapyr were showed the larval mortality of 57.3, 50.0 and 54.7% respectively at 72 h after application of treatment (Fig. 1b).

Larval mortality at 24 h post-treatment was used to determine the toxicity regression equations, LC50, and toxicity index. Emamectin benzoate, chlorantraniliprole, and chlorfenapyr were shown to be more dangerous than indoxacarb, thiamethoxam, and imidacloprid in the studies presented. The LC50 values for insecticides (emamectin benzoate and imidacloprid) ranged from 0.319 to 13.556 mg/L, respectively, at 24 h post-treatment. The LC50 values for chlorantraniliprole and chlofenapyr ranged from 0.562 to 0.931 mg/L. They were generally lower than conventional insecticides (indoxacarb, thiamethoxam, and imidacloprid) with LC50′s ranging from 1.223 to 13.556 mg/L. The LC50 values for insecticides (emamectin benzoate and imidacloprid) ranged from 0.785 to 55.229 mg/L, respectively, at 48 h post-treatment. The LC50 values for chlorantraniliprole ranged from 0.857 to 2.796 mg/L. They were generally lower than conventional insecticides (indoxacarb, thiamethoxam, and imidacloprid) with LC50′s ranging from 3.303 to 55.229 mg/L. The obtained results demonstrated that emamectin benzoate, chlorantraniliprole were meaningfully more toxic to early instar S. frugiperda larvae than other tested insecticides. The LC50 values for insecticides (emamectin benzoate and imidacloprid) ranged from 0.785 to 55.229 mg/L, respectively, at 72 h post-treatment. The LC50 values of chlorantraniliprole, ranged from 0.857 to 2.796 mg/L. They were generally lower than conventional insecticides (indoxacarb, thiamethoxam, and imidacloprid) with LC50′s ranging from 3.303 to 55.229 mg/L at 72 h post-treatment (Table 5). SE, χ2, df and CL indicate standard error, chi-square, degrees of freedom and confidence limits, respectively. When the 95% confidence intervals for two or more LC50 values for the same set of tested plants do not overlap (P 0.05), the results are statistically different.

Fit of probe line

Synthetic

Insecticides

Time

(Hours)

Slope ± SE

χ2

(df = 1)

P

value

LC50 (95% CL)

(mg/L)

Reg. equation

(

)

Toxicity

index

(%)

Emamectin benzoate

24

0.77 ± 0.11

0.04

0.10

0.32 (0.23–0.41) a

0.65 + 1.40 x

100.0

48

1.18 ± 0.12

1.39

0.71

0.79 (0.63–0.956) a

0.13 + 1.20 x

100.0

72

1.39 ± 0.15

7.15

0.07

0.26 (0.18–0.34) a

0.87 + 1.75 x

100.0

Indoxacarb

24

0.96 ± 0.11

1.42

0.70

2.39 (1.82–2.10) fghi

−0.36 + 0.96 x

13.36

48

0.78 ± 0.11

0.84

0.84

8.20 (6.09–12.511) hij

−0.71 + 0.78 x

9.57

72

1.02 ± 0.12

1.97

0.58

1.81 (1.35–2.28) bcd

−0.27 + 1.04 x

14.51

Imidacloprid

24

1.01 ± 0.11

0.34

0.95

13.56 (10.8–16.80) k

−1.14 + 1.00 x

2.35

48

0.10 ± 0.12

1.66

0.65

55.23 (40.90–85.55) l

−1.78 + 1.03 x

1.42

72

1.05 ± 0.12

0.48

0.92

8.92 (6.92–11.01) m

−1.01 + 1.06 x

2.95

Thiamethoxam24

0.71 ± 0.11

0.40

0.94

5.16 (3.09–7.22) j

−0.51 + 0.71 x

6.19

48

0.58 ± 0.11

0.24

0.97

10.31 (6.72–14.91) hijk

−0.58 + 0.58 x

7.61

72

0.70 ± 0.11

0.60

0.90

3.35 (1.69–5.02) l

−0.37 + 0.71 x

7.85

Chlorantraniliprole

24

1.06 ± 0.12

5.29

0.15

0.56 (0.42–0.71) b

0.27 + 1.10 x

56.76

48

0.82 ± 0.11

2.38

0.50

0.86 (0.63–1.11) ab

0.06 + 0.82 x

91.60

72

1.16 ± 0.13

2.71

0.00

0.39 (0.03–0.78) ab

0.50 + 1.33 x

66.92

Chlorfenapyr

24

0.82 ± 0.12

0.31

0.96

0.93 (0.52–1.34) bcd

0.03 + 0.82 x

34.26

48

0.70 ± 0.11

0.26

0.97

3.30 (2.38–4.47) cdef

−0.37 + 0.70 x

23.77

72

0.94 ± 0.12

0.33

0.96

0.72 (0.41–1.04) bcd

0.13 + 0.95 x

36.53

Probit regression analysis revealed that emamectin benzoate and chlorfenapyr with maximum LT50 values of 48.30 h (39.14–62.54), 53.19 (41.89–78.05), respectively, followed by chlorantraniliprole 82.55 h (51.70–415.34) against 2nd instar S. frugiperda while other synthetic insecticides were exhibiting LT50 values of 85.52 h (52.68–315.34) to 117.52 (75.54–715.34) treated with the lowest concentration of 3.125 mg/L.

At highest concentration of 50.0 mg/L, thiamentoxam and emamectin benzoate were proved to be effective exhibiting minmum LT50 values of 9.57 h (0.73–17.69) and 53.19 h (41.89–78.05) and 10.18 h (4.48–14.57) respectively, followed by chlorantraniliprole 10.57 (4.46–15.60) against 2nd instar S. frugiperda while other syntehtic insecticides were exhibiting LT50 values of 13.42 h (6.35–18.93) to 23.95 h (17.73–28.73) (Table 6). SE, χ2, df, CL and mg/L indicate standard error, chi-square, degrees of freedom, confidence limits and milligrams per liter, respectively.

Fit of probe line

Synthetic

Insecticides

Concentrations

(mg/L)

Slope ± SE

χ2

(df = 1)

P

value

LT50 (95% CL)

(hours)

Reg. equation

(

)

Emamectin benzoate3.125

1.33 ± 0.31

0.74

0.39

48.30 (39.14–62.54)

−2.24 + 1.33 x

6.25

1.34 ± 0.31

0.41

0.52

29.26 (19.39–36.36)

−1.95 + 1.33 x

12.5

1.32 ± 0.32

0.15

0.70

16.55 (6.85–23.44)

−1.59 + 1.31 x

25.0

1.49 ± 0.35

0.36

0.55

10.43 (3.21–16.49)

−1.48 + 1.47 x

50.0

2.80 ± 0.59

0.15

0.70

10.18 (4.48–14.57)

−6.72 + 4.02 x

Indoxacarb3.125

0.92 ± 0.32

0.37

0.54

117.52 (75.54–715.34)

−2.00 + 0.97 x

6.25

1.08 ± 0.31

0.17

0.68

71.27 (54.16–144.40)

−2.01 + 1.08 x

12.5

1.31 ± 0.31

0.48

0.49

40.71 (31.62–50.54)

−2.11 + 1.31 x

25.0

1.29 ± 0.31

0.65

0.42

25.15 (14.59–32.28)

−1.79 + 1.28 x

50.0

1.72 ± 0.33

0.34

0.56

16.75 (9.40–22.25)

−2.08 + 1.70 x

Imidacloprid3.125

1.93 ± 0.36

1.66

0.20

102.22 (80.20–164.31)

−4.00 + 2.00 x

6.25

1.48 ± 0.32

0.30

0.59

82.74 (65.01–137.08)

−2.86 + 1.49 x

12.5

1.54 ± 0.31

0.40

0.53

48.13 (40.20–59.45)

−2.60 + 1.54 x

25.0

1.67 ± 0.31

0.63

0.43

32.90 (25.68–38.90)

−2.53 + 1.67 x

50.0

2.01 ± 0.32

0.0.44

0.51

23.95 (17.73–28.73)

−2.74 + 1.99 x

Thiamethoxam3.125

0.60 ± 0.30

0.05

0.83

85.52 (52.68–315.34)

−1.15 + 0.60 x

6.25

0.66 ± 0.30

0.01

0.89

32.56 (2.36–49.54)

−1.00 + 0.66 x

12.5

0.72 ± 0.30

0.01

0.98

21.51 (0.70–33.19)

−0.96 + 0.72 x

25.0

0.73 ± 0.31

0.01

0.92

11.88 (0.02–22.75)

−0.78 + 0.73 x

50.0

1.01 ± 0.33

0.07

0.80

9.57 (0.73–17.69)

−0.98 + 1.00 x

Chlorantraniliprole3.125

0.61 ± 0.30

0.49

0.49

82.55 (51.70–415.34)

−1.17 + 0.61 x

6.25

0.66 ± 0.30

0.07

0.79

35.12 (3.63–55.97)

−1.02 + 0.66 x

12.5

0.78 ± 0.30

0.08

0.78

22.30 (2.37–33.25)

−1.05 + 0.78 x

25.0

0.89 ± 0.32

0.00

0.94

10.46 (0.40–19.55)

−0.91 + 0.89 x

50.0

1.98 ± 0.40

0.81

0.37

10.57 (4.46–15.60)

−2.19 + 2.08 x

Chlorfenapyr3.125

1.14 ± 0.31

0.38

0.54

53.19 (41.89–78.05)

−1.96 + 1.14 x

6.25

1.21 ± 0.31

0.27

0.61

32.11 (21.08–40.30)

−1.81 + 1.20 x

12.5

1.19 ± 0.31

0.14

0.71

20.64 (9.07–28.21)

−1.55 + 1.18 x

25.0

1.56 ± 0.33

0.22

0.64

15.77 (7.72–21.76)

−1.84 + 1.54 x

50.0

1.72 ± 0.33

0.02

0.88

13.42 (6.35–18.93)

−1.93 + 1.71 x

4 Discussion

The biorational insecticides have become an essential component for the development of integrated pest management approach. Many researchers are working to manage the S. frugiperda in field and laboratory by various control tactics to develop the effective control practice as a persistent approach (Susanto et al., 2021b). Opting for botanical and synthetic insecticides would not only economical but also an environmental protection (Pavela, 2009). The use of botanical and synthetic insecticides against S. frugiperda can provide moderate efficacy levels with other control measures, can lead to the effective management of S. frugiperda resulted in achieving better maize yields (Sisay et al., 2019).

The results of present study showed that mortality was concentration and time dependent against 2nd instar. Azadirachtin caused mortality of 45.30 and 96.70% at 24 and 120 h post-treatment, respectively. In line with the present study, azadirachtin was more effective in reducing the incidence in maize attacked by S. frugiperda larvae at one-week interval (Kammo et al., 2019). Azadirachtin and lufenuron showed highest larval mortality of 89.57 and 85.41%, respectively, against 6-day-old S. frugiperda (Tavares et al., 2010).

In the current research, pyrethrin induced 90.70% mortality in 2nd instar S. frugiperda at 120 h post-treatment. Pyrethrin shown very high efficiency against a variety of arthropod pests while having few negative effects on human health and the environment (Jeran et al., 2021). Pyrethroids have been reported as toxic against larvae and adult of S. frugiperda (Usmani and Knowles, 2001). The aqueous extract of tobacco leaf was applied by contact and residual assay gave larval mortality of 50.0 and 21.53% of S. frugiperda (Kardinan and Maris, 2021). The results further supported by (Sakadzo et al., 2020), where the extract of N. tabacum leaves toxic against early instar of S. frugiperda. The Nicotiana tabacum caused 62% larval mortality of S. frugiperda by feeding method (Phambala et al., 2020). Osthol is a coumarin compound play an essential role in plant defense responses (Chappell, 1995). Rotenone has a low level of insecticidal activity against tobacco cutworm, Spodptera litura (Li et al., 2017).

Mythimna separata and Agrotis ipsilon are controlled by Celastrus angulatus (Cheng et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2017). Matrine inhibited the development of early third-instar oriental armyworm larvae, Mythimna separata Walker (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) (Huang et al., 2017). It was shown that buprofezin was ineffective against Helicoverpa armigera at any of the doses studied. The populations of H. armigera were decreased and crop damage was much diminished when lufenuron was applied at both 37 and 49 g AI ha−1 (Gogi et al., 2021).

In response to consumers' increasing concern about their health, regulations governing allowable amounts of pesticide residue on fruits and vegetables have tightened. However, pesticides have lasting effects and might be employed as emergency control of many arthropods, notably lepidopteran pests, after analyzing the optimal dosage level with the least residual effects. Insecticides examined demonstrated substantial effectiveness against S. frugiperda larvae in their second instar, as seen by the findings.

The findings of the current investigation are corroborated by Kulye et al. (2021) who found that emamectin benzoate and chlorantraniliprole are poisonous to S. frugiperda. Emamectin benzoate and chlorantraniliprole are more harmful to S. frugiperda early instar larvae (Deshmukh et al., 2020).

5 Conclusions

The effectiveness of the biological insecticides, including botanical and unconventional insecticides against S. frugiperda 2nd instar larvae after pest invasion in China have been evaluated in this study for the first time. Buprofezin, azadirachtin, osthole, and pyrethrin, four botanical insecticides, significantly killed second instar larvae of S. frugiperda. Moreover, these biorational pesticides may be included in an integrated pest management strategy for the long-term control of S. frugiperda in smallholder farmer settings.

Funding

This research work was supported by Key-Area Research and Development Program of Guangdong Province (No. 2020B020223004) and GDAS Special Project of Science and Technology Development (No. 2020GDASYL-20200301003 and 2020GDASYL-20200104025). The authors extend their appreciation to the Researchers supporting project number (RSPD2023R686), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Acknowledgement

This research work was supported by Key-Area Research and Development Program of Guangdong Province (No. 2020B020223004) andGDAS Special Project of Science and Technology Development (No. 2020GDASYL-20200301003 and 2020GDASYL-20200104025). The authors extend their appreciation to the Researchers supporting project number (RSPD2023R686), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- A method of computing the effectiveness of an insecticide. J. Econ. Entomol.. 1925;18:265-267.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Damaging Nature of Fall Armyworm and its management practices in Maize: A Review. Tropical Agrobiodiversity. 2020;1:82-85.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of damage caused by evolved fall armyworm on native and transgenic maize in South Africa. Phytoparasitica. 2021;49

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The biochemistry and molecular biology of isoprenoid metabolism. Plant Physiol. 1995;107:1-6.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effects of celangulin IV and v from Celastrus angulatus maxim on Na+/K+-ATPase activities of the oriental armyworm (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) Journal of Insect Science. 2016;16

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Field Efficacy of Insecticides for Management of Invasive Fall Armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda (J. E. Smith) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) on Maize in India. Florida Entomologist. 2020;103:221-227.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, G.H., Gomez, K.A., Gomez, A.A., 1985. Statistical Procedures for Agricultural Research. Biometrics 41, undefined-undefined. https://doi.org/10.2307/2530673.

- First report of outbreaks of the fall armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda (J E Smith) (Lepidoptera, Noctuidae), a new alien invasive pest in West and Central Africa. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0165632.

- [Google Scholar]

- Efficacy of biorational insecticides against Bemisia tabaci (Genn.) In: And Their Selectivity for Its Parasitoid Encarsia Formosa Gahan on Bt Cotton. Sci Rep 11. 2021.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Potential invasion of the crop-devastating insect pest fall armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda to China. Plant Prot.. 2018;44:1-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Semisynthesis of some matrine ether derivatives as insecticidal agents. RSC Adv. 2017;7:15997-16004.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Protein baits, volatile compounds and irradiation influence the expression profiles of odorant-binding protein genes in Bactrocera dorsalis (Diptera: Tephritidae) Appl Ecol Environ Res. 2017;15:1883-1899.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effectiveness of Entomopathogenic Fungi on Immature Stages and Feeding Performance of Fall Armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) Larvae. Insects. 2021;12:1044.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pyrethrin from Dalmatian pyrethrum (Tanacetum cinerariifolium (Trevir.) Sch. Bip.): biosynthesis, biological activity, methods of extraction and determination. Phytochemistry Reviews. 2021

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Initial detections and spread of invasive Spodoptera frugiperda in China and comparisons with other noctuid larvae in cornfields using molecular techniques. Insect Sci. 2020;27:780-790.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kammo, E., Suh, C., Mbong, G., … S.D.-A., 2019, undefined, 2019. Biological versus chemical control of fall armyworm and Lepidoptera stem borers of maize (Zea mays). Agronomie Africaine 31, 187–198.

- Effect of botanical insecticides against Fall Armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda J. E. Smith (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) In: IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. IOP Publishing Ltd. 2021.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Fall armyworm invasion in Africa: implications for maize production and breeding. J Crop Improv 2020

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Baseline susceptibility of Spodoptera frugiperda populations collected in india towards different chemical classes of insecticides. Insects. 2021;12

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z., Huang, R., Li, W., Cheng, D., Mao, R., Zhang, Z., 2017. Addition of cinnamon oil improves toxicity of rotenone to Spodoptera litura (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) larvae.

- A simplified method of evaluating dose-effect experiments. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1949;96:99-113.

- [Google Scholar]

- Navik, O., Shylesha, A.N., Patil, J., Venkatesan, T., Lalitha, Y., Ashika, T.R., 2021. Damage, distribution and natural enemies of invasive fall armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda (J. E. smith) under rainfed maize in Karnataka, India. Crop Protection 143, undefined-undefined. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CROPRO.2021.105536.

- Effectiveness of some botanical insecticides against Spodoptera littoralis Boisduvala (Lepidoptera: Noctudiae), Myzus persicae Sulzer (Hemiptera: Aphididae) and Tetranychus urticae Koch (Acari: Tetranychidae) Plant Protection Science. 2009;45:161-167.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bioactivity of common pesticidal plants on fall Armyworm Larvae (Spodoptera frugiperda) Plants. 2020;9

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effectiveness of Different Soft Acaricides against Honey Bee Ectoparasitic Mite Varroa destructor (Acari: Varroidae) Insects. 2021;12

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- POLO: A User’s Guide to Probit or Logit Analysis. General Technical Report PSW-38. 1980

- [Google Scholar]

- Sakadzo, N., Makaza, K., Chikata, L., 2020. Biopesticidal Properties of Aqueous Crude Extracts of Tobacco (Nicotiana Tabacum L.) Against Fall Armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda J.E Smith) on Maize Foliage (Zea Mays L.) Diets. Agricultural Science 2, p47. https://doi.org/10.30560/AS.V2N1P47.

- The efficacy of selected synthetic insecticides and botanicals against fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda, in maize. Insects. 2019;10

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Toxicity and efficacy of selected insecticides for managing invasive fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda (J.E. Smith) (lepidoptera: Noctuidae) on maize in Indonesia. Research on Crops. 2021;22:652-665.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Selective effects of natural and synthetic insecticides on mortality of Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) and its predator Eriopis connexa (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) J Environ Sci Health B. 2010;45:557-561.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Toxicity of pyrethroids and effect of synergists to larval and adult Helicoverpa zea, Spodoptera frugiperda, and Agrotis ipsilon (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) J Econ Entomol. 2001;94:868-873.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Insight into the mode of action of celangulin V on the transmembrane potential of midgut cells in lepidopteran larvae. Toxins (Basel). 2017;9

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Impact of climate change on maize yield in China from 1979 to 2016. J Integr Agric. 2021;20:289-299.

- [Google Scholar]

- The host preference of Spodoptera frugiperda on maize and tobacco. Plant Protection. 2019;45:61-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Spodoptera frugiperda (JE Smith) was first discovered in Jiangcheng County of Yunnan Province in southwestern China. Yunnan Agriculture. 2019;1:72.

- [Google Scholar]

- Population occurrence, spatial distribution and sampling technique of fall armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda in wheat fields. Plant Protection. 2020;46:10-16.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of spatial arrangement of push-pull companion plants on fall armyworm control and agronomic performance of two maize varieties in Ghana. Crop Protection. 2021;145

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]