Translate this page into:

Analysis of synthetic food color additive, sugar, and mycotoxin content in traditional, cereal-based Sobia beverage using high-performance liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Objective

The traditional cereal-based fermented beverage, Sobia, is in high demand in the Arab community of the Middle East, particularly during the sacred month of Ramadhan. The sugar (fructose, glucose, and sucrose) content and presence of synthetic food color additives (tartrazine [E-102], sunset yellow [E-110], carmoisine [E-122], and brilliant black [E-151]) and major mycotoxins (aflatoxins, trichothecene [T-2], ochratoxins, and deoxynivalenol [DON]) in Sobia beverages from the western and central regions of Saudi Arabia were investigated for safety.

Methods

Sobia samples from anonymous vendors were collected, divided based on their apparent colors (red, dark red, white, or yellow), and prepared following a simple, “quick, easy, cheap, effective, rugged, and safe” extraction method. This was followed by high-performance liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry analysis.

Results

Sugars were present at the following concentrations: fructose: 0.69–33.81 mg/mL; glucose: 0.26–37.69 mg/mL; and sucrose: 0.30–149.67 mg/mL. Synthetic food colorants E-102 and E-122 were detected at concentrations of 0.22–1.37 µg/mL and 6.58–42.73 µg/mL, respectively. By contrast, E-110 and E-151 were found in only one sample at concentrations of 0.45 µg/mL and 152.87 µg/mL, respectively. The results of mycotoxin analysis revealed no aflatoxin B1, B2, G1, or G2 in any sample; however, T-2 and DON appeared at concentrations of 0.6–1.4 µg/mL and 1.15–38.5 µg/mL, respectively.

Conclusion

The results of this investigation of Sobia beverages revealed the presence of two mycotoxins. However, it eliminated the concern over the most carcinogenic mycotoxins: aflatoxins. It also illustrated the unmediated addition of sugars and synthetic food colorants (used to enhance taste and attract consumers) during Sobia production. Thus, there is an urgent need for responsible agencies to regulate Sobia production. Further investigation is required to assess the quality and health risks of Sobia beverages.

Keywords

Sobia

Mycotoxins

Food colorants

Sugar

1 Introduction

Traditionally fermented cereal-based beverages are consumed worldwide . Sobia is a popular homemade beverage produced by fermenting malt or wheat (Gassem, 2003). It is common in the central, western, and northwestern provinces of Saudi Arabia and is sold by street vendors during the holy month of Ramadhan. Observers of Ramadhan often break their fast by drinking Sobia, making it an important drink at the Muslim dining table.

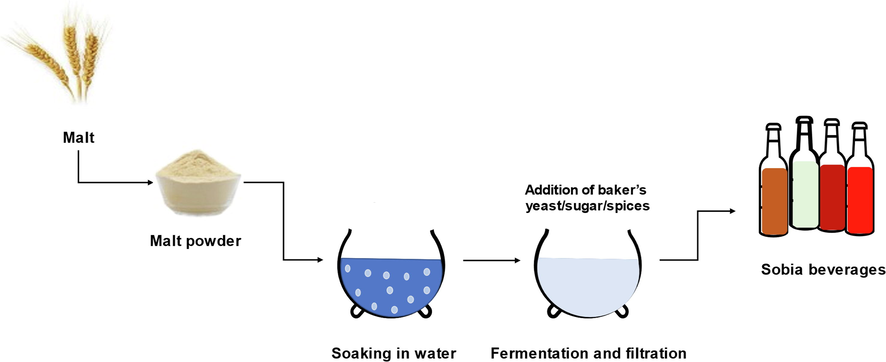

The production of Sobia involves multiple steps, as shown in Fig. 1. The process begins with the suspension of wheat or malt powder in water, followed by the addition of baker’s yeast, sugar, and spices (e.g., cardamom and cinnamon). Different natural flavors and colors, including raisins and raspberry syrup, may also be added to achieve the desired taste and appearance. The mixture is then left in a warm place (between 30 °C and 40 °C) for at least 24 h. Finally, the mixture is filtered, and the filtrate is placed in a sealed container without pasteurization and kept cold for marketing (Borai et al., 2021). The process of Sobia production undergoes little or no quality control, an oversight that may compromise its safety.

Flowchart depicting the process of Sobia production.

Food color additives are a part of Sobia production and are used in food, and drinks to enhance natural colors, compensate for color loss, and add colors to colorless foods (Amchova et al., 2015). Color additives may be comprised of natural compounds or organic and non-organic synthetic compounds, such as tartrazine (E-102), quinoline yellow, and sunset yellow (E-110). In order to avoid any risks associated with the use of food colorants, the addition of synthetic food additives is regulated by food safety authorities. However, due to increasing public health concerns, the European Parliament and European Council have commissioned the European Food Safety Authority to re-evaluate the toxicity of synthetic food colorants, specifically those evaluated before 20 January 2009 (Amchova et al., 2015).

The presence of mycotoxins in cereal-based foods is another serious public health concern. Mycotoxins are small, poisonous secondary metabolites produced by major pathogenic fungi, such as Aspergillus, Fusarium, and Penicillium (Alshannaq & Yu, 2017). Over 300 mycotoxins have been discovered; however, only a few, including aflatoxins (AFs), ochratoxins, fumonisins, patulin, zearalenone, deoxynivalenol (DON), and trichothecene (T-2), are associated with food contamination (Alshannaq & Yu, 2017). Though good agricultural practices may be implemented, fungi can still infect growing crops, such as barley and wheat, and grow on foods under storage. Thus, mycotoxin contamination of foods is an unavoidable and unpredictable issue that threatens food safety (Alshannaq & Yu, 2017).

Although there is no upper bound for the tolerable consumption of sugar, a high intake of free sugars is linked with low dietary quality, obesity, and the risk of developing non-communicable diseases (Amine et al., 2003). Free sugars are defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as monosaccharides and disaccharides added to foods and beverages by manufacturers, procedures, and consumers, as well as sugars naturally present in honey, syrups, fruit juices, and fruit juice concentrate. Therefore, the WHO strongly advises reducing the intake of free sugars throughout the course of one’s lifetime and provides guidance to limit the intake of free sugars to less than 10% of one’s total daily energy intake (WHO, 2015). In addition, the Saudi Food and Drug Authority (SFDA) has banned the addition of sugar or any natural or artificial sweeteners in the preparation of fresh and mixed fruit juices. Few studies have been conducted to evaluate the safety of Sobia beverages. Borai et al., (2021) studied the effect of storage conditions on the ethanol content of Sobia and the impact of different storage conditions on microbial growth Borai et al., (2022). Another study by Abulreesh et al. (2022) assessed the microbiological quality and safety of Sobia. In the present study, the safety of Sobia produced in Saudi Arabia was investigated by assessing the concentration of four synthetic food pigments (tartrazine, sunset yellow, carmoisine [E-122], and brilliant black [E-151]), free sugars (glucose, fructose, and sucrose), and four major mycotoxins (AFs, T-2, ochratoxin A [OTA], and DON).

2 Materials and Methods

2.1 Chemicals

Mycotoxin (AF, OTA, T2, and DON) standards were obtained from Trilogy Analytical Laboratory (Missouri, USA), while synthetic food color additive (E-102, E-110, E-122, and E-151) standards were obtained from the SFDA (Riyadh, Saudi Arabia). Other chemicals, including fructose, glucose, sucrose, ammonium acetate, and acetonitrile (high-performance liquid chromatography [HPLC]-grade) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Water was treated in a Milli-Q water purification system (Millipore, Molsheim, France) to obtain HPLC-grade water.

2.2 Samples

Sobia samples were obtained from anonymous vendors in western and central provinces of Saudi Arabia. A total of 14 samples were collected, divided by color, and coded with letters and numbers. The letter A was given to samples obtained from west regions, and T for samples obtained from central region. All samples were kept at –20 °C until use.

2.3 Sample preparation

Samples were prepared according to the method described by Ntrallou et al., (2020). In short, 10 mL of Sobia sample were centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 15 min, then filtered through 0.45 µm syringes before injection into HPLC systems for synthetic food colorant and sugar content analysis.

There is no established procedure or the preparation and extraction of malt- and wheat-based juices for mycotoxin analysis. Thus, the “quick, easy, cheap, effective, rugged, and safe” (QuEChERS) method, with slight modification, was applied to prepare and extract mycotoxins from the Sobia samples (González-Jartín et al., 2019). Specifically, 10 mL of acetonitrile containing 1% formic acid was added to 10 mL of Sobia sample in a 50 mL polypropylene tube and shaken for 30 min using a laboratory shaker. A buffer salt mixture (4 g MgSO4 + 1 g NaCl + 1 g trisodium citrate dehydrate + 0.5 g disodium hydrogen citrate sesquihydrate) was then added, and the tube was shaken vigorously by hand for 1 min. After that, the sample was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 5 min. The top acetonitrile layer was extracted and micro-filtered using a 0.2 µm filter and transferred into a new 15 mL centrifugation tube. Following this, 0.1 mL of the extract was added to 0.4 mL of mobile phase A and B [1:1] and transferred to a vial for analysis.

2.4 Synthetic food color additive analysis by HPLC-diode array detector (DAD)

Samples were analyzed for synthetic food color additives using HPLC (Agilent Technologies) with column Zorbax SB-C18 (250 × 4.6 mm; 5 μm) and detector 1260 DAD-VL. A 10 nM ammonium acetate solution was used for mobile phase A, and acetonitrile was used for mobile phase B. The flowrate was 1 mL/min, with an optimized gradient program (A:B) of 95:5 initially and 50:50 after 30 min. Absorbance was monitored at 426 nm for E-102, 482 nm for E-110, 514 nm for E-122, and 613 nm for E-151. Peaks were identified and quantified using the retention times of standard absorption spectra.

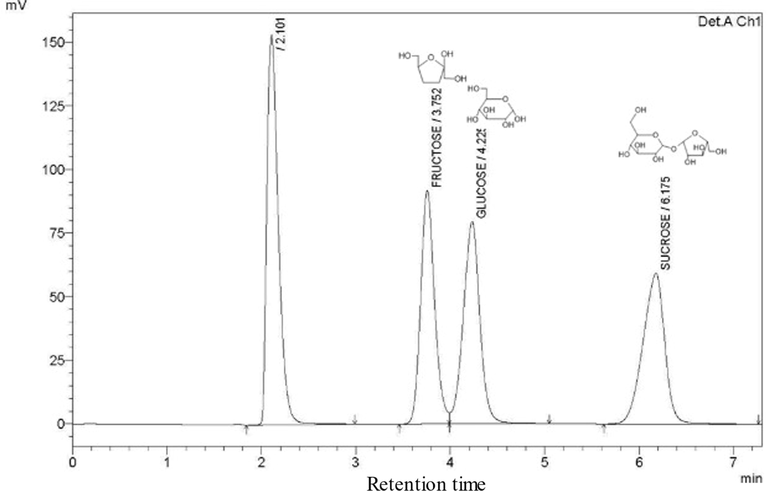

2.5 Sugar analysis by HPLC-refractive index detector (RID)

Fructose, glucose, and sucrose were analyzed using a Shimadzu HPLC system (Salamatullah et al., 2021) equipped with a prominence LC-10AB binary pump and a SIL-20A autosampler (Kyoto, Japan). Analysis was conducted using a mobile phase of 85% HPLC-grade aqueous acetonitrile at an isocratic flow rate of 1 mL/min. Compounds of interest were separated using a Shimadzu LC-NH2 column (15 × 4.6 mm; 5 µm) and identified using a RID-10A Shimadzu detector (Kyoto, Japan). Subsequently, 10 µL of each sample was injected into the HPLC system, and the peak retention times of fructose, glucose, and sucrose were compared to standards and analyzed using a Shimadzu LabSolutions LC WorkStation v. 1.22 (Kyoto, Japan).

2.6 Mycotoxin analysis by ultra-HPLC-positively charged electrospray ionization (ESI + )-mass spectrometry (MS)/MS

Aflatoxins, OTA, T-2, and DON were analyzed using a Sciex Triple Quad 6500 LC-MS/MS System equipped with analytical column Kinetex™ Cl8 (100 mm × 2.1 mm; 2.6 µm) at 40 °C. Mobile phase A was 5 mM of ammonium formate in water (0.2% formic acid), and mobile phase B was methanol (0.2% formic acid). The ultra-HPLC-(ESI + )-MS/MS gradient program is detailed in Supplementary Table 1 (Liao et al., 2013). ND = not detected.

Sobia sample

Artificial food colorant concentration (µg/mL ± SD)

Color

ID

Tartrazine

(E-102)Sunset yellow

(E-110)Carmoisine

(E-122)Black PN

(E-151)

Red

A1

ND

ND

34.07 ± 0.03

ND

A2

ND

ND

42.73 ± 0.16

152.97 ± 0.69

A3

ND

ND

18.09 ± 0.31

ND

A4

ND

ND

13.94 ± 0.02

ND

A5

ND

ND

20.57 ± 0.01

ND

T

ND

ND

6.58 ± 0.01

ND

Dark red

T

ND

0.45 ± 0.01

ND

ND

White

A1

0.22 ± 0.02

ND

ND

ND

A2

ND

ND

ND

ND

A3

1.37 ± 0.25

ND

ND

ND

A4

0.28 ± 0.02

ND

ND

ND

A5

ND

ND

ND

ND

T

0.93 ± 0.07

ND

ND

ND

Yellow

T

ND

ND

ND

ND

TF

ND

ND

ND

ND

2.7 Statistical analysis

Statistical calculations were completed using Microsoft Excel, 2019 (Microsoft, Seattle, WA, USA). The experiments were independently analyzed in three times, and data were presented as arithmetical mean ± standard deviation.

3 Results and discussion

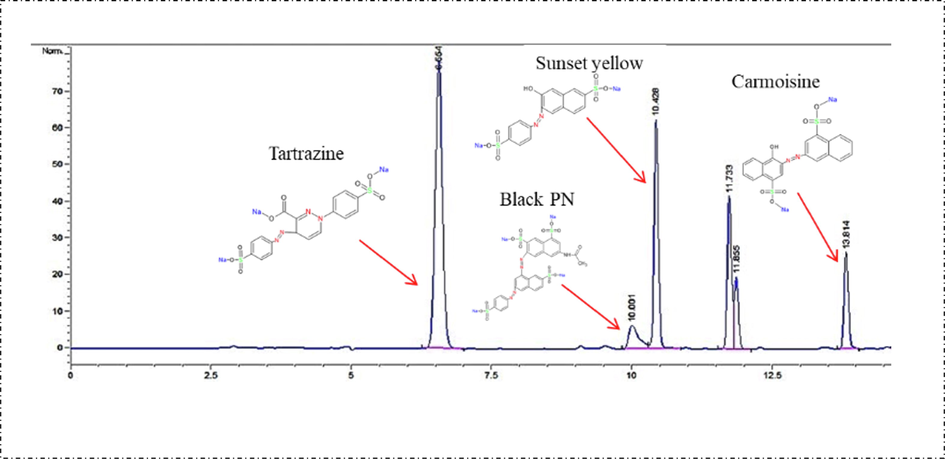

3.1 Synthetic food color additive analysis by HPLC-DAD

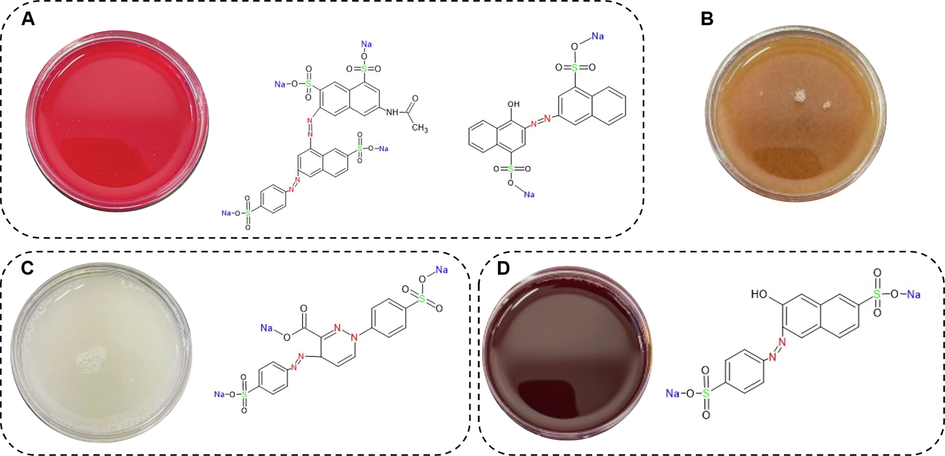

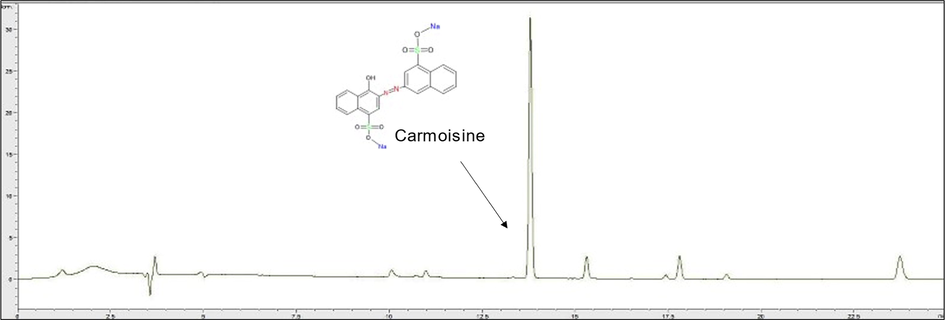

The results of the analysis of 14 Sobia beverage samples by HPLC-DAD for the presence of four synthetic food colorants are presented in Fig. 2 and Table 1. The data show that all red Sobia samples contained varying concentrations of E-122, ranging from 6.58 to 42.73 µg/mL. These results indicate that the intended use of E-122 in Sobia beverages is to impart a red color (see Figs. 3 and 4). Among all samples, Red A2 contained E-151 colorant at a high concentration (152.97 µg/mL) (Table 1). The only dark red Sobia sample analyzed in this study contained E-110 colorant at a concentration of 0.45 µg/mL. Most white Sobia samples showed low concentrations of E-102, ranging from 0.22 to 1.37 µg/mL, while yellow Sobia drinks showed no added synthetic food colorants (Fig. 3 and Table 1).

HPLC Chromatogram of synthetic food color standards.

Association between Sobia and food colorant additives (A) red Sobia and brilliant black (left) and carmoisine (right) (B) yellow Sobia (C) white Sobia and tartrazine (D) dark red Sobia and sunset yellow.

HPLC Chromatogram of synthetic food colorant, carmoisine, detected in red Sobia T sample.

Tartrazine is one of the most common additives used in the production of juices and drinks in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia (Ahmed et al., 2021). Ahmed et al. report the high intake of juices and drinks containing E-102 and E-110 by male (303–442 mL/day) and female (283–314 mL/day) Saudi children and the use of E-110 in juices and drinks at concentrations of 0–225 µg/mL (Ahmed et al., 2023). These findings confirm that the consumption of Sobia drinks with added colorants could increase exposure rates to synthetic food colorants, potentially compromising the health of Saudi Arabian consumers.

3.2 Sugar analysis by HPLC-RID

An analysis of sugar (fructose, glucose, and sucrose) content was undertaken to evaluate the nutrient energy content of Sobia. The results of HPLC-RID analysis revealed that fructose and glucose (monosaccharides) were found in all samples at low to moderate concentrations ranging from 0.26 to 37.69 mg/mL (Fig. 5 and Table 2). Sucrose was detected in all Sobia samples at varying concentrations, from 0.3 to 149.67 mg/mL. The sugar content of Hardaliye, a fermented beverage produced from grapes, was found to be 120–320 mg/mL and not less than 200 mg/mL in warm areas (Aydoğdu et al., 2014), indicating that the ripening of grapes in the production of fermented beverages could increase the total sugar content. However, Sobia production does not involve any fruit ripening. The use of sucrose, then, is for the purposes of increasing the fermentation rate and enhancing flavor, regardless of the total resultant energy intake in the form of free sugars. ND = not detected.

HPLC Chromatogram of fructose, glucose, and sucrose standards.

Sobia sample

Sugar concentration (mg/mL ± SD)

Fructose

Glucose

Sucrose

Color

ID

Red

A1

4.93 ± 0.66

5.26 ± 0.92

100.39 ± 0.43

A2

0.69 ± 0.08

0.26 ± 0.0

100.87 ± 0.84

A3

27.70 ± 0.38

30.66 ± 0.45

0.30 ± 0.12

A4

8.75 ± 0.3

8.93 ± 0.27

113.06 ± 0.36

A5

2.70 ± 0.01

2.89 ± 0.02

138.57 ± 0.23

T

5.00 ± 0.06

5.97 ± 0.43

145.12 ± 1.04

Dark red

T

4.20 ± 1.01

3.53 ± 0.94

137.35 ± 0.19

White

A1

3.17 ± 0.22

0.40 ± 0.09

67.75 ± 0.43

A2

30.01 ± 0.33

32.52 ± 0.92

42.56 ± 0.5

A3

11.88 ± 0.89

0.66 ± 0.1

89.84 ± 0.72

A4

6.52 ± 0.17

0.37 ± 0.02

149.67 ± 1.2

A5

33.81 ± 0.14

37.69 ± 0.15

54.21 ± 0.24

T

12.27 ± 0.12

1.61 ± 0.16

118.08 ± 1.1

Yellow

T

16.04 ± 0.98

15.41 ± 0.98

105.24 ± 0.61

TF

ND

ND

ND

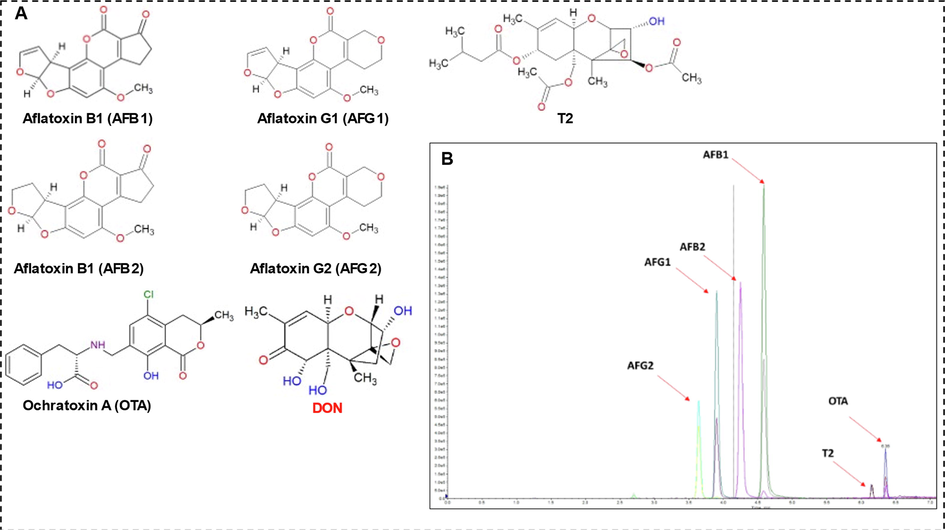

3.3 Mycotoxin analysis by ultra-HPLC (ESI + )-MS/MS

The results of mycotoxin analysis by ultra-HPLC-MS/MS (Fig. 6 and Table 3) show that AFs (B1, B2, G1, and G2) and OTA were not detected in all Sobia samples. Conversely, DON was found in most samples, with concentrations ranging from 1.15 to 38.5 ng/mL, and T-2 toxin was detected in Red A2, White A, and White A4, with concentrations of 1.4, 1.14, and 0.6 ng/mL, respectively. These findings are in agreement with analyses of alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverages on the European market (Carballo et al., 2021). The data show that DON is the mycotoxin most frequently detected in Sobia beverages, while T-2 is the least. Further, Al-Taher et al. (2013) found that T-2 was detected in only 11% of samples, with a mean level of 0.3 ng/mL. United States Food and Drug Administration regulations set the limit for DON concentration in cereals and cereal-based products at 1,000 ng/mg. European regulations are stricter, at 50–200 ng/mg (Alshannaq & Yu, 2017). For ready-to-use foods, such as juices and drinks, there are currently no regulations concerning DON or T-2 content. The Joint Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO)/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JEFCA) and the Scientific Committee on Food recommend a total daily intake of T-2 (including hydrolized T-2) and DON of 100 ng/kg and 1,000 ng/kg, respectively (FAO, 2001). Thus, the presence of DON and T-2 in juices and drinks must be actively regulated. AF = aflatoxins; T-2 = trichothecene; OTA = ochratoxin A; DON = deoxynivalenol; ND = not detected.

(A) Chemical structures of analyzed mycotoxins (B) U-HPLC-(ESI + )-MS/MS chromatogram of the analyzed mycotoxins standards.

Sobia sample

AFs (B1, B2, G1, and G2)

(ng/mL)T-2 (ng/mL)

OTA (ng/mL)

DON (ng/mL)

Color

ID

Red

A1

ND

ND

NDND

A2

1.4

38.5

A4

ND

ND

A4*

ND

19.5

A5

ND

5.36

T

ND

ND

Dark red

T

ND

6

White

A1

1.14

6.66

A2

ND

30.1

A3

ND

24.7

A4

0.6

1.15

A5

ND

ND

T

ND

ND

Yellow

T

ND

ND

TF

ND

6.9

4 Conclusion

In conclusion, the addition of food colorants and sugars in Sobia production appears to be poorly controlled, creating a potential for health risks among consumers. Food authority agencies must take legal action to regulate and supervise the Sobia market in Saudi Arabia. Mycotoxin analysis showed an absence of AFs and OTA, as well as low levels of DON and T-2. Due to a lack of accepted procedures for Sobia preparation, ionization efficiency could affect the detection of mycotoxins. Interfering low-molecular-weight compounds, such as sugars and pigments, could decrease ionization and lead to false negatives in mycotoxin detection . Therefore, further investigation is needed to establish and validate a procedure for mycotoxin extraction and analysis in Sobia beverages.

Acknowledgments

The author extends their appreciation to the Deputyship for Research and Innovation, “Ministry of Education” in Saudi Arabia for funding this research (IFKSUOR3-392-1). The author would also like to thank Alzahrani, A., Ahmed, MA., and Alahmari, D. for their assistance in this research.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Microbiological quality and safety assessment of (Sobia) a traditionally fermented beverage of western Saudi Arabia. Asian J. Microbio., Biotech. Envir. Sci.. 2022;23(1):144-152.

- [Google Scholar]

- Dietary intake of artificial food color additives containing food products by school-going children. Saudi J. Biol. Sci.. 2021;28(1):27-34.

- [Google Scholar]

- Average daily intake of artificially food color additives by school children in Saudi Arabia. J. King Saud Univ. - Science.. 2023;35(4):102596

- [Google Scholar]

- Occurrence, toxicity, and analysis of major mycotoxins in food. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health.. 2017;14(6):632.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rapid method for the determination of multiple mycotoxins in wines and beers by LC-MS/MS using a stable isotope dilution assay. J. Agric. Food Chem.. 2013;61(10):2378-2384.

- [Google Scholar]

- Health safety issues of synthetic food colorants. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol.. 2015;73(3):914-922.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diet, nutrition, and the prevention of chronic diseases: World Health. Organization. 2003;916 technical report series.

- [Google Scholar]

- A study on production and quality criteria of hardaliye; a traditional drink from Thrace region of Turkey. Gıda. 2014;39(3):139-145.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ethanol content of a traditional Saudi beverage Sobia. Int. J. Food Prop.. 2021;24(1):1790-1798.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effect of storage temperature and duration on the microbial growth in Sobia: a Saudi Arabian traditional drink. J. Saudi Soc. Food Nutr.. 2022;15(1):1-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Dietary exposure to mycotoxins through alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverages in Valencia. Spain. Toxins.. 2021;13(7):438.

- [Google Scholar]

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization). ''Safety Evaluation of Certain Mycotoxins in Food. In FAO Food and Nutrition Paper, The Fifty-sixth meeting of the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA); Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations'': Rome, Italy, 2001; 74, p. 705.

- Physico-chemical properties of Sobia: A traditional fermented beverage in western province of Saudi Arabia. Ecol. Food Nutr.. 2003;42(1):25-35.

- [Google Scholar]

- A QuEChERS based extraction procedure coupled to UPLC-MS/MS detection for mycotoxins analysis in beer. Food Chem.. 2019;275:703-710.

- [Google Scholar]

- Analytical and sample preparation techniques for the determination of food colorants in food matrices. Foods.. 2020;9(1):58.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bioactive and antimicrobial properties of eggplant (Solanum melongena L.) under microwave cooking. Sustainability.. 2021;13(3):1519.

- [Google Scholar]

- Guideline: Sugars intake for adults and children. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Guidelines Review Committee; 2015.

Appendix A

Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2023.102736.

Appendix A

Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article: