The impact of the yttrium oxide nano particles Y2O3 on the in vitro fertilization and in vitro culture media in a mouse model

⁎Corresponding author.

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Introduction: Oxidative stress has a critical role in affecting in vitro fertilization (IVF) outcomes. The yttrium oxide nanoparticle (Y2O3 NPs) known as free radicals’ scavenger. The reactive oxygen species (ROS) has an essential role in the pathological effect of oxidative stress. The study aimed to evaluate the Y2O3 NPs effect on the in vitro fertilization media and in vitro culture media in mice as a mammalian model. Methods: The NPs of Y2O3 tested in two different concentrations, 25 μg/ml, and 50 μg/ml, to examine nanoparticle effect on cleavage rate and blastula rate by exposing the gametes cell for 6 h during the fertilization and 5 days on culture media till embryos reach the blastula stage. The Y2O3 NPs cubic shape, and the sizes used to be in the range of 18 ± 5 nm as measured by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and 11.14 nm as measured by X rays diffractions (XRD). The results showed that the rate of blastocyst was significantly higher in the in the treated by adding the 25.ug/ml Y2O3 NP and the control groups than the higher treated group with 50ug/ml NP, group by the ad of Y2O3 nanoparticles. While the cleavage rate was unaffected by the Y2O3 nanoparticles. In conclusion the treatment of the Y2O3 in the IVF and early embryo development have no side effects except in higher rate in the blastula stage.

Keywords

Nanoparticles

Y2O3

In vitro fertilization

Mice

Embryo

1 Introduction

1-1 The in vitro fertilization (IVF) is one of the assisted reproductive technologies (ART) with the intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) and embryo transfer (ET), (Allen et al.,2006; Nagy et al.,2019). Mice tend to be the most popular and used model for embryo manipulation for human IVF due to the physiological processes and handling with short reproductive cycle and the first-choice methods in embryology (Zhao et al., 2011; Ménézo, and Hérubel, 2002). Although the IVF-treatment helps in infertility cases, but due to expose gametes and embryos to the external environment, which affects its successful rate. Serval factors affecting the IVF, The most important elements that can negatively impact the success of ART include things like culture media, gas phase, plasticware, oil overlay, absence of cytokines/growth hormones, pH shock, osmotic shock, temperature variations, UV light damage, and oxidative stress. (Du Plessis et al., 2008; Gardner, and Kelley, 2017). Gametes and embryos generate free radicals by means of ATP production through mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, glycolysis, aerobic metabolism, and anaerobic metabolism. Certain media may contain metallic ions, including supplements supplied to the embryo culture media. These supplements can often surpass the oxidant load, such as the serum-containing amine oxidase, resulting in excessive generation of H₂O₂. The oxygen atom's partial pressure in the In vitro culture media exceeds the in vivo level, and at 37° C, the O₂ concentration in the medium with ambient oxygen is 20-fold greater than the intracellular O₂ concentration in vivo, which leads to activates oxidase enzymes that generated free radical (Du Plessis et al., 2008; Gardner, and Kelley, 2017) Nanotechnology applications have experienced significant growth and diversification across multiple sectors including medical, electronics, transportation, energy, environment, and space exploration over the past decade. (Nikalje, 2015). The inorganic nanomaterials comprised of metal and metal oxide nanoparticle which manufactured into metals for exemple Au or Ag NPs, metal oxides such as TiO₂ and ZnO NPs, Y₂O3 NPs, CeO₂ NPs (Jeevanandam,et al., 2018; Lee et al., 2016). The CeO₂ nanoparticles and Y₂O3 nanoparticles are used as anti-microbial and antioxidants. In 2018, Godugu et al., studied the protective effects of Y2O3 NPs against cardiac injury on mouse remodel by isoproterenol and Raw 264.7 cells, the in vivo result showed a free radical scavenging response by treating Y2O3 NPs and reducing cardiotoxicity caused by isoproterenol. The Y2O3 NPs treatment inhibited proinflammatory cytokines expression and protected histo-architecture, heart rhythm. The in vitro studies showed free radical scavenging activity, and Y2O3 treated cells showed reduced oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation. In 2017, Rajakumar et al. (2021) reported the multiple application of Y2 O3 NPs, used as a grain-refining additive and deoxidizer. Tang, 2020 illustrated the biomedical application of Y2O3, such as drug delivery, biosensors, bioimaging, fluorescence imaging, and anticancer therapies. The antioxidant and anti-microbial properties of the Y2O3 NPs reported in various investigations,such as the nontoxic behavior of Y2O3 was observed at concentrations up to 100 μg/ml (Tang, 2020). In 2020, Akhtar et al., evaluated the biological reaction of Y2O3NPs in human breast carcinoma MCF-7 & fibroblast HT-1080 cells and compared it with the results of antioxidative CeO₂ NPs and pro-oxidative ZnO NPs (Akhtar et al., 2020).

The Y₂O3 nanoparticles' antioxidant properties prevented cell death due to excessive oxidative stress and were nontoxic to macrophages and neutrophils, which is beneficial for potential wound healing., (Hosseini et al., 2013, and, Godugu et al., 2018.

1-2 -So, the aim of the study is to evaluate the role and effect of yttrium oxide nanoparticles on in vitro mice embryo production. In addition to compare the different concentrations of yttrium oxide nanoparticles on in vitro mice embryo production.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Preparation and Characterization of Yttrium Oxide Nanoparticles (Y₂O3 NPs)

The Y₂O3 NPs purchased from Sigma Aldrich as nano powder material < 50 nm particle size, Selvaraj et al.2014 Siddhardha et al., 2020 Transmission Electronic Microscopy (TEM) completed the nanoparticle characterization for the size, shape, and phase (TEM) and X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) in King Abdullah Institute for Nanotechnology (KAIN) (Mourdikoudis et al. 2018). The nano powder was dissolved in Milli Q water (1 mg/1ml) inside a sonicator's glass tube and used for all experiments as a stock solution (Grana Dávila et al. 2018). Before the nanoparticles were added to the IVF & IVC dishes media, the ultrasonication method sonicator (Ultasonic,FS20H, Fisher Scientific, Park Lane Pittsburg, PA, USA) was followed (40 Waves × for 10 min) to avoid nanoparticle agglomeration before exposure to the cells (Alarifi et al., 2017; Takeo, and Nakagata, 2018). The nanoparticles were immediately added to IVF dishes: 2.5 μl in the drop of the first treatment group and 5 μl in the second treatment group drop. In the IVC, dishes were supplemented with 4.5 μl in the drops of the first treatment group and 9 μl in the second treatment group's drops.

2.2 Animal treatment

Research Ethical Community at the King Saud University approved No.SE-19-136 was obtained after submission of the experimental protocol and animal handling procedure. The laboratory Mus musculus mice strain SWR/J, male between the ages of 3 and 6 months, and females between the ages of 6 and 8 weeks.

2.3 Spermatozoa Collection

The mice males (15 SWR/J, 30–35 gm weight) was euthanasia sacrificed method of exposure to 80 % CO₂ / 20 % O₂ for 120 s in a sealed chamber then dissected and the two cauda epididymides removed. Then two cauda epididymides transferred to paraffin oil in the sperm collection dish, which contains two drops of about 400 μl of human tubular fluid (HTF) medium (Irvine Scientific -Corporate 2511 Daimler Street Santa Ana, CA 92705, USA. Catalog #90125) covered with mineral paraffin oil Sigma M5310. Prior to beginning sperm collection, the dish was set up in an incubator with 5 % CO2 and 37℃ temperature control. This process should be completed at least 30 min before the collection begins.(CO2 Lab Incubator Heraeus Instruments, Function line, Thermo Scientific). An incision was made in each cauda epididymis under the oil, the suspension of sperm was allowed to capacitate by placing it in an incubator (37℃, 5 % CO2 in air) for 60 min before fertilization (Takeo, and Nakagata, 2018).

2.4 Oocytes Collection: Hormonal treatment for superovulation

The Female mice (45 SWR/J, 25–30 gm. weight) were injected intraperitoneally (IP) with 7.5 IU of equine chorionic gonadotropin (eCG) (Serigan 6000 IU, Ovejero, Ctran. Leon-Vilecha, Spain) between 4:00 to 5:00 pm of Day 1, after 48 h, the same mice receive 7.5 IU (IP) injection of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) (Choriomon 5000 IU, Instiut Biochimique SA 6903 Lugano, Switzerland). Ovulation occurred approximately 15–17 h after the hCG injection (Takeo, and Nakagata, 2018; Alhimaidi et al.2022). The cumulus - oocytes complexes (COCs) were collected from the oviducal ampullae at 15 h after hCG injection. The female mice were sacrificed as the same way male were treated, then dissected, and the two oviductal ampullae were removed, transferred to the oocyte collection petri dish (BD Falcon 353001), containing a drop (200 μl.) of (HTF) medium with five more small drops. The fertilization dishes and oocyte collection dishes were set up at least 30 min before the oocyte collection. They were then put in an incubator that was set to 37℃ and had 5 % CO2 in the air. Directly after ampullae collection, an incision was made in each ampulla by using the needle of insulin syringe to open the ampulla and drag (COCs) into the HTF medium drops.(Takeo, and Nakagata, 2018; Alhimaidi et al.2022).

2.5 In vitro Fertilization IVF

The fertilization dishes were prepared and placed in an incubator (37℃, 5 % CO2 in air) for at least 30 h to allow the medium equilibration. For the insemination one million sperm/ml from sperm suspension was added to COCs drop. After insemination, the fertilization dishes placed in an incubator (37℃, 5 % CO₂ in air) for 6 h Takeo, and Nakagata, 2018; Alhimaidi et al.2022).

2.6 Embryo Culture

The potassium simple optimization medium (KSOM)(TBS-8071 Lot no 200110, Tri-bioscience, Sunnyvale CA, USA). a culture dishes were pre-prepared for a minimum of 30 min prior to use, and that has been acclimated in a CO₂ incubator. After 6 h of fertilization, the oocytes were transferred into a 60 mm petri dishes containing hyaluronidase enzyme covered with mineral paraffin oil to remove cumulus cells mechanically using a glass pasture pipette, and the denuded oocytes transferred to the culture medium, then the fertilized oocytes cultured for 4–5 days until the blastocyst stage reached in a 5 % CO2 incubator at 37 °C (Takeo, and Nakagata, 2018; Alhimaidi et al.2022).

2.7 Experimental Design Y₂O3 Nano particles treatments

After oocytes collection, oocytes were divided into three major groups, the control group and 2 treatment groups, depending on the Y₂O3 nanoparticles concentration, 1st group (25 μg/ml), and 2nd group (50 μg/ml). The treatment starts with IVF and during the embryo culture medium as stated before. Then the fertilized oocytes cultured until the blastocyst stage which approximately reached at 4th-5th day after fertilization in a 5 % CO2 incubator at 37 °C (Takeo, and Nakagata, 2018; Bakhtari et al., 2020).

2.8 Statistical analysis

The IVF, cleaved embryos rates data, and blastocyst rate was tested by the Package for social sciences (SPSS) Software version 20. Before analysis, the normality and equal variance were tested using Histogram, Box Plot, and then compared by one way-ANOVA, followed by multiple pairwise comparisons using the Tukey’s test. Data presented as mean ± SEM. Differences considered significant if the P-value was less than (0.05). All the experiments were replicated at least three times.

3 The Results

3.1 Characterization of Yttrium Oxide Nanoparticles (Y₂O3 NPs)

3.1.1 By the transmission electronic microscope (TEM) for (Y₂O3 NPs)

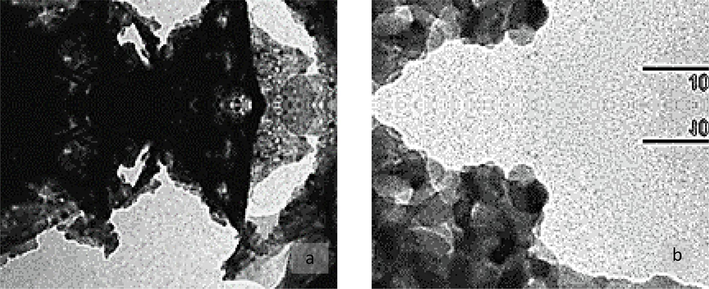

The shapes of yttrium oxide Y2O3 mostly cuboidal, and the size of crystallite is ∼ 18 ± 5 nm (∼500 nm with nano-agglomeration) (Fig. 1 (a) and (b)) showing a crystallinity surface (Fig. 1 a) at low resolution and (Fig. 1 b) at higher resolution.

- (a) and (b). Transmission electron micrograph (TEM) micrographs of nano-yttrium oxide Y2O3 NPs: (a) low- and (b) high-resolution image.

3.1.2 By the X rays diffractions (XRD) analysis results

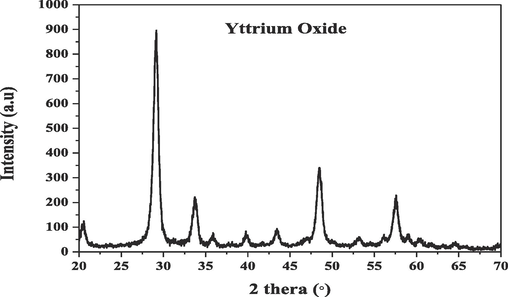

The X rays diffractions XRD patterns of the yttrium oxide Y2O3 nano powders (Fig. 2) obtained by using the database of International Centre for Diffraction Data (ICDD) powder diffraction file database card file No. 89-5591. The yttrium oxide Y2O3was crystalline and had no second-phase or impurity peaks. Scherrer's equation used to calculate the average yttrium -oxide Y2O3 nano powders crystallites size (L) from the peak at 2θ = 29.08° (Balzar, and Popa, 2002):

- X- Ray Diffraction (XRD) patterns of Yttrium-oxide Y2O3 NPs nano powders.

The crystallite size was 11.14 nm, which is slightly lower than the TEM imaging value.

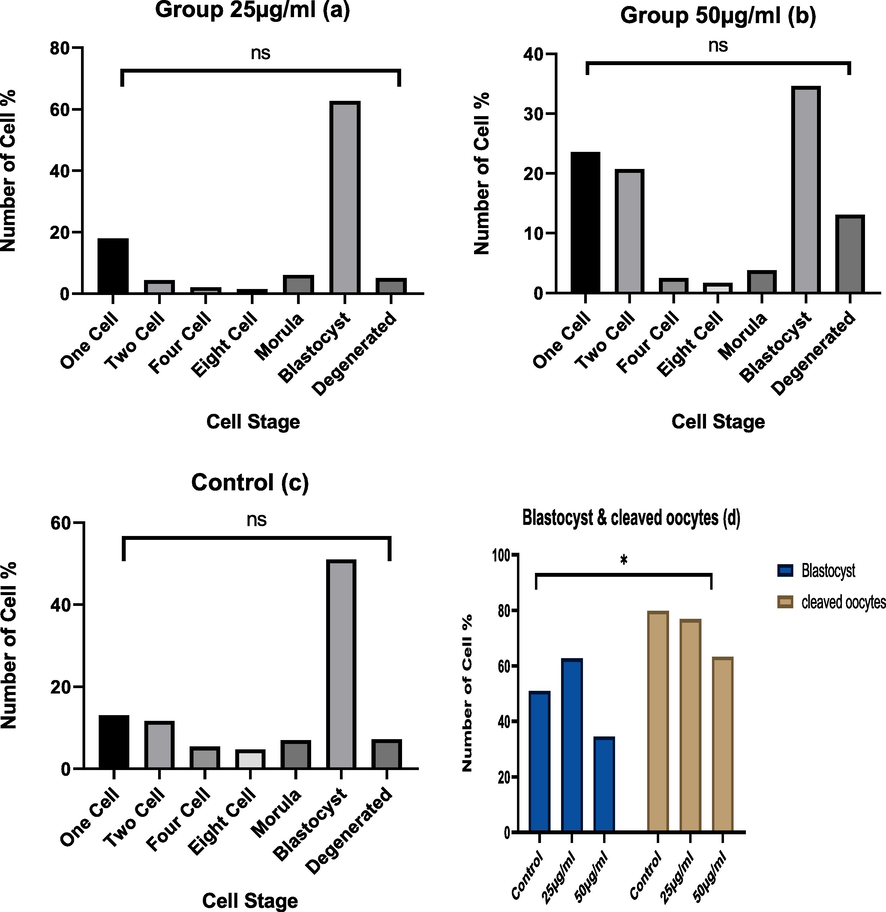

3.2 The In vitro Fertilization (IVF) and in vitro Culture of mouse embryos

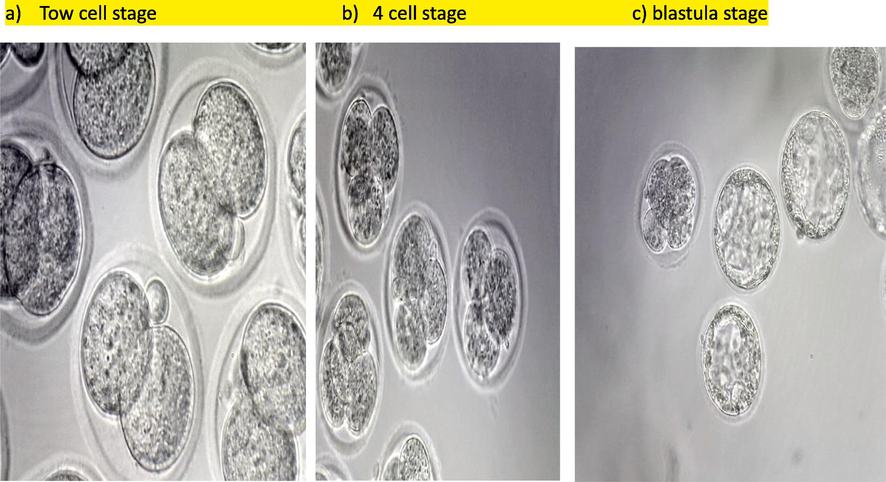

The total number of ova collected from mice control group female were 443 ova, the 1st treated group Y₂O3 (25ug/ml) 472 ova and the 2nd treated group Y₂O3 (50ug/ml) 237 ova. The results of different concentrations (25 µg/ml and 50 µg/ml) of Y₂O3 NPs assessed on early embryonic development of mice oocytes are presented in Table 1. There were no significant differences within and between the treated and the control groups in comparing each cell stage of early embryo development from 1 cell till morula stage (Fig. 3-a, b,and c). While the mean of the blastocyst stage showed significant differences (P < 0.05) between the control and the 1st treated group compared to 2nd treated group (mean ± SE = 56.50 ± 5.67 and 73.75 ± 10.30 compared to 20.50 ± 2.72), respectively Table 1 and (Fig. 3.d). In addition, the result of the different development stages which showed some variations between the three groups, such as in the 2nd treated group most of the ova remained in 1 cell stage and at the degenerated ova compared to the 1st treated and control groups (Fig. 3 a, b, and c). In addition, (Fig. 3.d) compared among the 3 groups in the totally different early embryo development stages, the 1st treated group embryo cleavage rate 363/443, 76.9 % = 80.0 + SE 7.34), the 2nd treated group (shoed the lowest rate 150/237, 63.3 % = 72.92 + SE 8.42), compared to the control group (354/443, 79.9 % =81.24 + SE 5.06). While the blastula stages, which showed some significant variations in blastula stage especially in the 1st treated group showed the highest rate (296/363. 81.5 % = 89.90 + SE 11.29) compared to the 2nd treated group (82/150,63 % = 66.47 + SE 16.51) and the control group 226/354 63.8 % = 65.01 + SE 9.33) at P (<0.05). Fig. 4 illustrates the picture of some different developmental embryo’s stages.

| ls No./ (cells %), (Mean ± SE) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One cell stage % &±SE | Total No. of oocytes | Stage of developing. =========Group | Eight Cellstage % &±SE | Four Cellstage % &±SE | Two Cellstage % &±SE | Blastocyst stage % &±SE | Morulastage % &±SE | Degeneratedstage % &±SE |

| 57/ (13 %)---------- (14.25 ± 5.89) a | 443 | Control (0 µg/ml) 15 female | 21/ (4.7 %)---------- (5.25 ± 3.35) a | 24/ (5.4 %)--------------- (6 ± 2.67) a | 52 / (11.7 %)----------- (13 ± 5.26) a | 226/ (51 %)------------ (56.50 ± 5.67) a* | 31/ (7 %)---------- (7.75 ± 2.05) a | 32 / (7.2 %)---------------- (8 + 4.06) a |

| 85/ (18.01 %)________(28.33 ± 14.43) a | 472 | Group 1 (25 µg/ml) 15 female | 7/ (1.5 %)---------- (1.75 ± 1.43) a | 10/ (2.12 %)_________(2.50 ± 1.32) a | 21/ (4.45 %)_______(5.25 ± 3.03) a | 296/ (62.71 %)---------- (73.75 ± 10.30) b* | 29/ (6.14 %)---------- (7.25 ± 4.13) a | 24/ (5.1 %)------------ (8 + 6.11) a |

| 56/ (23.62 %)_______(14.00 ± 8.67) a | 237 | Group 2 (50 µg/ml) 15 female | 4/ (1.7 %)______(1.00 ± 1.00) a | 6/ (2.53 %)_________(1.50 ± 0.64) a | 49/ (20.7 %)______(12.25 ± 8.37) a | 82/ (34.6 %)__________(20.50 ± 2.723) c* | 9/ (3.8 %)______(2.25 ± 1.43) a | 31/ (13.1 %)_________ (7.75 + 6.48) a |

a /b /c: significantly differences at the same column at P 0 < 0.05. at the same row.

* significantly differences at P 0 < 0.05. at the same row.

- a, b, c and d.) The effect of Y 2O 3 NPs (a) treated with 25ug/ml, or (b) 50 ug/ml, compared to (c) control on early mice embryonic devolvement and (d) blastula rate. * Significant at (P < 0.05).

- The in vitro fertilization (IVF) of mice early embryonic cleavage stages and Blastula. Tow cell stage b) 4 cell stage c) blastula stage.

4 Discussion

4.1 Characterization of Yttrium Oxide Nanoparticles (Y₂O3 NPs)

In the current study, which may be considered as the first time studied the potential role of Y2O3 NPs in vitro fertilization and early stage of development in vitro on mice embryo. Nanoparticles often show different properties from the original material it synthesizes by (Mourdikoudis et al. 2018). The nanoparticle's characterization is necessary to know the probabilities and the application of the new material. The characterization parameters that excessively studied were the size and the shape of nanoparticles (Mourdikoudis et al. 2018). Our nanoparticle characterization result showed a cubic shape and a size 18 ± 5 nm by TEM. While x-ray diffraction showed 11.14 nm size of the nanoparticle, which is smaller than the size of the TEM. The difference in nanoparticles' size due to the calculation method between TEM and XRD techniques (Andelman et al., 2010). In a previous study, the nanoparticle's shape was cubic, and the size was 35 ± 10 nm (Akhter et al. 2020). In the present study, the x-ray diffraction result showed impurity peaks. In a previous study, the breakdown of peaks occurs when the particle size is small, so the average size of yttrium oxide nanoparticles by the XRD technology was between 3 nm and 4 nm (Andelman et al., 2010). The Y2O3 NPs reported in previous studies as antioxidative and protective against oxidative stress damage in differential cells type and retinal origin (Hossain et al.2015; Khaksar et al., 2017; Grana et al. 2018) which agreed with our study. Additionally, Y2O3 NPs therapeutic effect was reported in oxidative stress-related disease (Song,et al., 2019).

4.2 In-vitro Fertilization

May be for the first time, the current study evaluated the role of adding the Y₂O3 NPs in the culture media of in vitro mouse embryos development. The present study results showed that exposure of sperm and oocyte to Y₂O3 NPs for 5 h in fertilization medium and culture medium for 5th days, indicate some significant changes in cleavage and blastocyst rates. The result of this study showed some variations compared with the previous study, that showed the (Y₂O3 NPs) (35 ± 10 nm) did not work as an antioxidant enzyme-like activity, non-oxidative, and biocompatible in the human breast carcinoma MCF-7 and fibroblast HT-1080 cells (Akhter et al. 2020). The biocompatible behavior was due to the high surface reactivity of (Y₂O3 NPs) that interact with the culture media component and formation NP-protein corona, which is an aid in biocompatibility (Akhter et al. 2020). While the other studies showed the antioxidative properties of Y₂O3 NPs, in mice macrophage cell line and hepatic failure of murine model Y₂O3 NPs (40––100 nm in size) which showed antioxidant and anti-inflammatory in vitro studied, and oxidative inhibition stress, inflammatory response, and cell apoptosis, liver injury (Song,et al., 2019). Owing to the high free energy of Y₂O3 NPs and normalize inflammatory mediator expression by impeding of ROS/NF-κB pathway (Song,et al., 2019). As stated by previous study reported that NPs of Y₂O3 (zeta sizer;175.34 ± 15.5 nm) work as an antioxidative, anti-inflammatory, and antifibrotic effects on macrophages cells and isoproterenol-induced cardiotoxicity mice remodel. Due to the free radical scavenging activity of nano-yttria and the inhibition of cardiotoxicity, pro-inflammatory cytokines, and protective effect in histo-architecture and rhythm of the heart (Godugu,et al., 2018). The anti-pancreatitis activity of Y₂O NPs at a sizer; 159.2 ± 7.5 nm) via inhibited mitochondrial and endoplasmic reticulum stress by the decrease of the Nrf2/NFκB pathway (Khurana et al., 2019). The protective effect observed in photoreceptor cells in the murine model by pro-treatment with Y₂O3 NPs (∼10–14 nm in diameter) (Mitra, 2014). The neuroprotective and antioxidative effects of nano-yttria (5.61–18.2 nm) showed in PC12 cells only and in combination with CeO₂ nanoparticles (Ghaznavi et al., 2015). In rat hippocampal, the nanoyttria showed protective effect only and combined with CeO₂ nanoparticles (Schubert et al., 2006). The antiapoptotic effect of the combination of Y₂O3 and CeO₂ nanoparticles was reported in β-cells of isolated rat pancreatic islets (Hosseini et al., 2013). Another previous study showed recovery in the rat pancreas model after treatment of Y₂O3NPs only and combined with CeO₂ NPs by inhibition oxidative stress and apoptosis (Khaksar et al., 2017). The synergetic effect of Y₂O3 NPs (30–50 nm in size) was observed in human cells line combined with nano-zinc oxide (Grana 2018). On the other hand, Y₂O3 NPs (41 ± 5 nm in size) have been reported to be cytotoxic in the HEK293 cells and inhibit cell proliferation 50 % at concentration 108 μg/ml The result of the current study showed that Y2O3 NPs (18 ± 5 nm) have a non-antioxidative effect and non-cytotoxic effect in the culture media of early embryonic development in a mouse model, which agree with Rajakumar, et al study about the safety using Y2O3 NPs Biomedical Applications.

5 Conclusion

The nanoparticle of Y₂O3 in size of 18 ± 5 nm at concentration 25 μg/ml and 50ul/gm. showed non-cytotoxic effects on sperms and oocytes cells by suspension to the in vitro fertilization (HTM) medium, and in the mouse embryo clutter medium (KSOM). The nanoparticle of Y₂O3 at concentrations 25 μg/ml and 50 μg/ml did not affect the cleavage rates in a mouse model. While the nanoparticle of Y₂O3 at concentrations 25 μg/ml and the control give better results than the 50 μg/ml in the blastocyst rates in a mouse model. So from the result of this study, we can conclude the benefit to use the Y2O3 in the farm animal fertilization to improve animal feedstock industries.

6 Recommendations

More study recommended to illustrate the genetic level to evaluate any alteration in the genetic material to evaluate the effect of Y₂O3 NPs on fertilization rate, embryo development rate. Also, it should be studied and examined in vivo effect of Y₂O3 NPs on the pregnant females and offspring on mouse model.

Funding

This research was funded by the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSP-2024/R232), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author contributions

Hissah I. Alhusayni: Methodology, experimental design, data collection; Muath G. Al Ghadi: the Idea of the research experimental design, material purchasing, and flow up the work; Ahmad R. Alhimaidi: team work management, writing the manuscript correspondent author and Funding acquisition; Aiman A. Ammari: review & editing the manuscript; Ramzi A. Amran: Experiment Animal handling and flow up, and fingers management; Nawal M. Al-Malahi: data analysis and data curation.

Acknowledgement

The authors sincerely express their thanks to the Researcher Support Project at King Saud University, Riyadh Saudi Arabia. for their help and support in funding this study.

Consent to participate

All authors consent to participate in the manuscript publication

Consent for publication

All authors approved the manuscript to be published.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- The role of the hot foot gene in the fertility of the in vitro fertilization and embryonic development of young adult and old mice as a model for assisted reproductive technology. Journal of King Saud University – Science. 2022;34:102060.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Akhter Mohd Javed, Ahamed Maqusood, Alrokayan Salman A., Ramamoorthy Muthumareeswaran M., and Alaizeri ZabnAllah M. 2020. High Surface Reactivity and Biocompatibility of Y2O3 NPs in Human MCF-7 Epithelial and HT-1080 Fibro-Blast Cells Molecules 2020, 25(5), 1137; https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25051137.

- Alarifi, S., Ali, D., and Alkahtani, S. 2017. Oxidative stress-induced DNA damage by manganese dioxide nanoparticles in human neuronal cells. BioMed Research International, Vol.2017. ID 5478790 https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/5478790.

- Pregnancy Outcomes After Assisted Reproductive Technology. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada. 2006;28(3):220-233.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and cytotoxicity of Y 2O 3 Nanoparticles of various morphologies. Nanoscale Research Letters. 2010;5(2):263-273.

- [Google Scholar]

- Grana Ángela Dávila, González Lara Diego, Fernández África González, Vázquez Rosana Simón. 2018. Synergistic effect of metal oxide nanoparticles on cell viability and activation of MAP Kinases and NFκB. Int J Mol Sci 15;19(1):246. DOI: 10.3390/ijms19010246.

- Cerium and yttrium oxide nanoparticles against lead-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis in rat hippocampus Cerium and yttrium oxide nanoparticles against lead-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis in rat hippocampus. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2015;164(1):80-89.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effects of dextran-coated superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles on mouse embryo development, antioxidant enzymes and apoptosis genes expression, and ultrastructure of sperm, oocytes, and granulosa cells. International Journal of Fertility and Sterility. 2020;14(3):161-170.

- [Google Scholar]

- Improved modeling of residual strain/stress and crystallite size distribution in Rietveld refinement. Adv. X-Ray Anal.. 2002;45:152-157.

- [Google Scholar]

- Impact of oxidative stress on IVF. Expert Review of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2008;3(4):539-554.

- [Google Scholar]

- Impact of the IVF laboratory environment on human preimplantation embryo phenotype. Journal of Developmental Origins of Health and Disease. 2017;8(4):418-435.

- [Google Scholar]

- The neuro-protective effects of cerium and yttrium oxide nanoparticles on high glucose-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis in undifferentiated PC12 cells. Neurological Research. 2015;37(7):1-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nanoyttria attenuates isoproterenol-induced cardiac injury. Nanomedicine. 2018;13(23):2961-2980.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antiapoptotic effects of cerium oxide and yttrium oxide nanoparticles in isolated rat pancreatic islets. Human and Experimental Toxicology. 2013;32(5):544-553.

- [Google Scholar]

- Review on nanoparticles and nanostructured materials: History, sources, toxicity and regulations. Beilstein Journal of Nanotechnology. 2018;9(1):1050-1074.

- [Google Scholar]

- Protective effects of cerium oxide and yttrium oxide nanoparticles on reduction of oxidative stress induced by sub-acute exposure to diazinon in the rat pancreas. Journal of Trace Elements in Medicine and Biology. 2017;41:79-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Yttrium oxide nanoparticles reduce the severity of acute pancreatitis caused by cerulein hyperstimulation. Nanomedicine: Nanotechnology, Biology, and Medicine. 2019;18:54-65.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial treatment of different metal oxide nanoparticles: A critical review. Journal of the Chinese Chemical Society. 2016;63(4):385-393.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mouse and bovine models for human IVF. Reproductive Biomedicine Online. 2002;4(2):170-175.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mitra Rajendra N., Merwin Miles J., Han Zongchao , Conley Shannon M., Al-Ubaidi Muayyad R., Naash Muna I. 2014. Yttrium oxide nanoparticles prevent photoreceptor death in a light-damage model of retinal degeneration. Free Radical Biology and Medicine Volume 75, October 2014, Pages 140-148 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.07.013.

- Vitro Fertilization: A Textbook of Current and Emerging Methods and Devices (2nd ed.). Springer; 2019.

- Nikalje, A. P. 2015. Nanotechnology and its Applications in Medicine. Medicinal Chemistry, 5(2). :5:081-089. DOI:10.4172/2161-0444.1000247. Rajakumar, G.; Mao, L.; Bao, T.; Wen,W.;Wang, S.; Gomathi, T.; Gnanasundaram, N.; Rebezov, M.; Shariati, M.A.; and Chung, I.-M.; 2021. Yttrium Oxide Nanoparticle Synthesis: An overview of Methods of Preparation and Biomedical Applications. Appl. Sci. 11, 2172. https://doi.org/10.3390/app 11052172.

- Cerium and yttrium oxide nanoparticles are neuroprotective. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2006;342(1):86-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- Selvaraj Vellaisamy, Bodapati Sravanthi, Murray Elizabeth, Rice Kevin M, Winston Nicole, Shokuhfar Tolou, Zhao Yu, and Blough Eric. 2014. Cytotoxicity and genotoxicity caused by yttrium oxide nanoparticles in HEK293 cells. Int J Nanomedicine 12; 9:1 379-91. doi:10.2147/IJN.S52625.

- Book. Model Organisms to Study Biological Activities and Toxicity of Nanoparticles, Springer. Singapore Pte. Limited; 2020.

- Therapeutic effect of yttrium oxide nanoparticles for the treatment of fulminant hepatic failure. Nanomedicine. 2019;14(19):2519-2533.

- [Google Scholar]

- Characterization techniques for nanoparticles: comparison and complementarity upon studying nanoparticle properties. Nanoscale. 2018;2018(10):12871.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- In vitro fertilization in mice. Cold Spring Harbor Protocols. 2018;2018(6):415-421.

- [Google Scholar]

- The potential role of nanoyttria in alleviating oxidative stress biomarkers: Implications for Alzheimer’s disease therapy. Life Sciences. 2020;259(July):118287

- [Google Scholar]

- In vitro fertilization: Four decades of reflections and promises. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta - General Subjects. 2011;1810(9):843-852.

- [Google Scholar]