Translate this page into:

Juglanin cures polyethylene microplastics-induced testicular damage in rats

⁎Corresponding author. nazia.ehsan@uaf.edu.pk (Nazia Ehsan)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Abstract

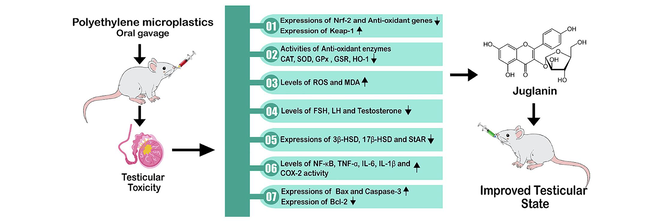

The current research was planned to evaluate the ameliorative role of juglanin (Jug) against polyethylene microplastics (PEMP) prompted testicular impairments. 48 rats were allocated in 4 groups: control, PEMP exposed, Jug + PEMP co-administrated and Jug supplemented group. The activities of antioxidant enzyme, inflammatory markers level, hormonal level, the expressions of steroidogenic enzymes, pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic protein were assessed after the 56 days of the trial. PEMP intoxication significantly disturbed Nrf-2/Keap-1 pathway and the biochemical profile of rats. However, the administration of Jug markedly increased Nrf-2 and anti-oxidant enzymes expressions, besides decreased the Keap-1 expression. Jug administration also increased Catalase (CAT), super oxide dismutase (SOD) glutathione reductase (GPx), glutathione peroxidase (GSR) and Hemeoxygenase-1 (HO-1) activities. On the other hand, the levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and malondialdehyde (MDA) were decreased following Jug administration. Moreover, Jug administration decreased the levels of inflammatory markers. Additionally, Jug administration increased luteinizing hormone (LH), testosterone, follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) levels and steroidogenic enzymes expression including 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (17β-HSD), steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR) and 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3β-HSD) expressions. Jug administration decreased Caspase-3 and Bax expressions, while increasing Bcl-2 expression. Therefore, the current findings suggested that Jug can remarkably alleviate PEMP induced testicular damage due to its therapeutical potentials.

Keywords

Polyethylene microplastics

Juglanin

Testicular damage

Oxidative stress

Inflammatory markers

1 Introduction

Plastics is extensively used in healthcare, agriculture and many other industries due to its excellent physical and chemical properties (Jambeck et al., 2015; Rochman and Hoellein, 2020). It is reported that by the year 2050, there will be 33 billion tons of plastic products on the planet (Phillips and Bonner, 2015). Microplastics (MPs) are ubiquitous environmental pollutants that are produced by the fragmentation of large plastic products into tiny plastic particles (diameter < 5 mm). MPs are recognized as a fourth major environmental problem along with ozone depletion, acidification of ocean and climate change (Jambeck et al., 2015; Galloway and Lewis, 2016)). MPs can infiltrate the human body through many routes. They can penetrate in the body via food chain, drinking water (Kosuth et al., 2018) and by consuming sea salt (Yang et al., 2015). Several reports have illustrated that MPs induce a significant detrimental effects on the growth rate and the survival of different animals. MPs move via bloodstream into various organs to induce damage to human health by stimulating the inflammatory responses (Vethaak and Legler, 2021).

Polystyrene (PS), polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP) and polyester are main types of MPs. PEMP is the prevalent type of MPs, abundantly present in terrestrial and aquatic habitats. PEMP accounts for 93 % of all MPs used and it is also present in personal care and cosmetic products to enhance its cleaning properties (Gouin et al., 2015). Recently a study has been reported that illustrates the damaging impacts of PEMP on the testicular tissues. PEMP disturbs the antioxidant enzymatic profile as well as promotes the production of ROS (Ijaz et al., 2022a). PEMP significantly induces morphological damage to sperm head, tail and mid-piece while, it also reduces sperm motility and epididymal sperm count. Moreover, exposure to PEMP also lowers the hormonal level (testosterone, LH and FSH) (Ijaz et al., 2022a).

Flavonoids are plant-based chemicals that are widely used in medicine. They are found in fruits, nuts, vegetables, grains and legumes (Ahmad et al., 2023). Juglanin (Jug) is a flavonoid extracted from raw Polygonum aviculare. Jug shows multiple therapeutical potentials including anti-inflammatory, anti-cancer, anti-apoptotic, neuroprotective and anti-oxidant (Wei et al., 2022). According to the previous literature plant based anti-oxidant named as rhamnetin can be used to treat PS-MPs induced testicular damage in rats (Hamza et al., 2023a). However, literature is yet unavailable that demonstrates the curative effects of Jug against PEMP induced testicular damage. Therefore, keeping the therapeutical potentials of Jug under consideration the present research was performed to evaluate the curative effects of Jug against PEMP induced testicular damage in rats.

2 Material and methods

2.1 Chemicals used

PEMP (CAS No. 9002-88-4, Size: 35–50 μm) with monodispersed shape were bought from Sigma Aldrich (Germany) and Jug (CAS No. 5041–67-8) from ALFA Chemistry.

2.2 Experimental animals

48 albino rats (6–8 weeks old, 170 ± 35 g) were housed in the animal room of University of Agriculture, Faisalabad (UAF). Rats were housed in cages with normal circadian rhythms (12 hrs light/dark cycle), standard (21–25 °C), temperature as well as adequate amount of moisture (50–60 %). Food and tap water were provided to the rats. The animals were handled according to the protocol of the European Union of Animal Care and Experimentation (CEE Council 86/609) that was further approved by the ethical committee of UAF.

2.3 Experimental layout

The animals (n = 48) were categorized into 4 groups (n = 12). Different doses of Jug and PEMP were administrated to the following groups; Control (0.9 % saline), PEMP administrated group (1.5 mgkg−1 of PEMP), Jug + PEMP co-administrated group (30 mgkg−1 of Jug + 1.5 mgkg−1 of PEMP) and Jug treated group (30 mgkg−1). The dose of PEMP was selected according to previous study (Ijaz et al., 2022a), while the dose of Jug was selected according to the study of Wei et al. (2022). Furthermore, oral toxicity analysis of Jug was performed with 30, 60, 90, 120 and 150 mgkg−1 doses. Health parameters such as diet, changes in weight, fluid intake, and psychomotor changes were measured. Jug did not show any toxicity at all the tested doses. So lowest dose (30 mgkg−1) was selected. The doses of PEMP and Jug were given simultaneously. All the doses were administered daily through oral gavage. Rats were anesthetized by using ketamine (60 mg/kg) and xylazine (6 mg/kg) after 56 days of trial, decapitated and trunk blood was drawn into sterilized tubes. Serum samples were obtained by centrifuging the blood at 1000 g for 15 min at room temperature and stored at –20 °C for biochemical assays. Following dissection, right testes of rats were kept at −80 °C to monitor enzymatic activities. The left testes were homogenized in Na3PO4 buffer solution at 12000 rpm for 14–15 min. Finally, various parameters were evaluated using the supernatant.

2.4 Antioxidant and oxidants assay

Catalase (CAT) and Super oxide dismutase (SOD) activities were evaluated by using the protocol of Aebi (1984) and Kakkar et al. (1984) respectively. The methodology of Lawrence and Burk (1976) as well as Carlberg and Mannervik (1975) was used to evaluate glutathione reductase (GPx) as well as glutathione peroxidase (GSR) activities. Hemeoxygenase-1 (HO-1) activity was measured by following Magee et al. (1999) protocol. The level of malondialdehyde (MDA) was assessed by using the methodology of Placer et al. (1966). Reactive oxygen species (ROS) level was measured by following the protocol of Hayashi et al. (2007).

2.5 Analysis of inflammatory indices

The levels of NF-κB (CSB-E13148r), TNF-α (CSB-E07379r), IL-1ß (CSB-E08055r), IL-6 (CSB-E04640r) and COX-2 activity (CSB-E13399r) were measured with the help of ELISA kit (YL Biotech Co. Ltd., Shanghai, China). The analyses were accomplished using ELISA Plate according to the company's instructions (BioTek, Winooski, USA).

2.6 Hormonal assay

The levels of FSH (serial number-H101), LH (serial number-H206) and plasma testosterone (serial number-H090) were determined by using enzyme linked immune-sorbent assay (ELISA) kits (Los Angeles, CA USA) according to the manufacturer’s procedures.

2.7 Real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

Nrf-2/Keap-1, apoptotic markers steroidogenic enzymes expressions were appraised via RT-qPCR. The total RNA of the cell was isolated by using a Tri-ZOL and its concentration was determined with a Nano-Drop 2000c spectrophotometer. The isolated RNA was transcribed into cDNA with a Fast Quant RT kit (Takara, China). Variations in the expressions were estimated by 2 -ΔΔCT and β-actin was taken as a standard control (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). Table 1 depicted the primer of the genes (Hamza et al., 2023b; Ijaz et al., 2022b).

Gene

Primers 5′ −> 3′

Accession number

Nrf-2

F: ACCTTGAACACAGATTTCGGTG

NM_031789.1

R: TGTGTTCAGTGAAATGCCGGA

Keap-1

F: ACCGAACCTTCAGTTACACACT

NM_057152.1

R: ACCACTTTGTGGGCCATGAA

CAT

F: TGCAGATGTGAAGCGCTTCAA

NM_012520.2

R: TGGGAGTTGTACTGGTCCAGAA

SOD

F: AGGAGAAACTGACAGCTGTGTCT

NM_017051.2

R: AAGATAGTAAGCGTGCTCCCAC

GPx

F: TGCTCATTGAGAATGTCGCGTC

NM_030826.4

R: ACCATTCACCTCGCACTTCTCA

GSR

F: ACCAAGTCCCACATCGAAGTC

NM_053906.2

R: ATCACTGGTTATCCCCAGGCT

GST

F: TCGACATGTATGCAGAAGGAGT

NM_031509.2

R: CTAGGTAAACATCAGCCCTGCT

HO-1

F: AGGCTTTAAGCTGGTGATGGC

NM_012580.2

R: ACGCTTTACGTAGTGCTGTGT

Bax

F: GGCCTTTTTGCTACAGGGTT

NM_017059.2

R: AGCTCCATGTTGTTGTCCAG

Bcl-2

F: ACAACATCGCTCTGTGGAT

NM_016993.1

R: TCAGAGACAGCCAGGAGAA

Caspase-3

F: ATCCATGGAAGCAAGTCGAT

NM_012922.2

R: CCTTTTGCTGTGATCTTCCT

β-actin

F: TACAGCTTCACCACCACAGC

NM_031144

R: GGAACCGCTCATTGCCGATA

2.8 Statistical analysis

Results were depicted as Mean ± SEM. One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s test was used to compare the groups. The level of significance was set at P<0.05.

3 Results

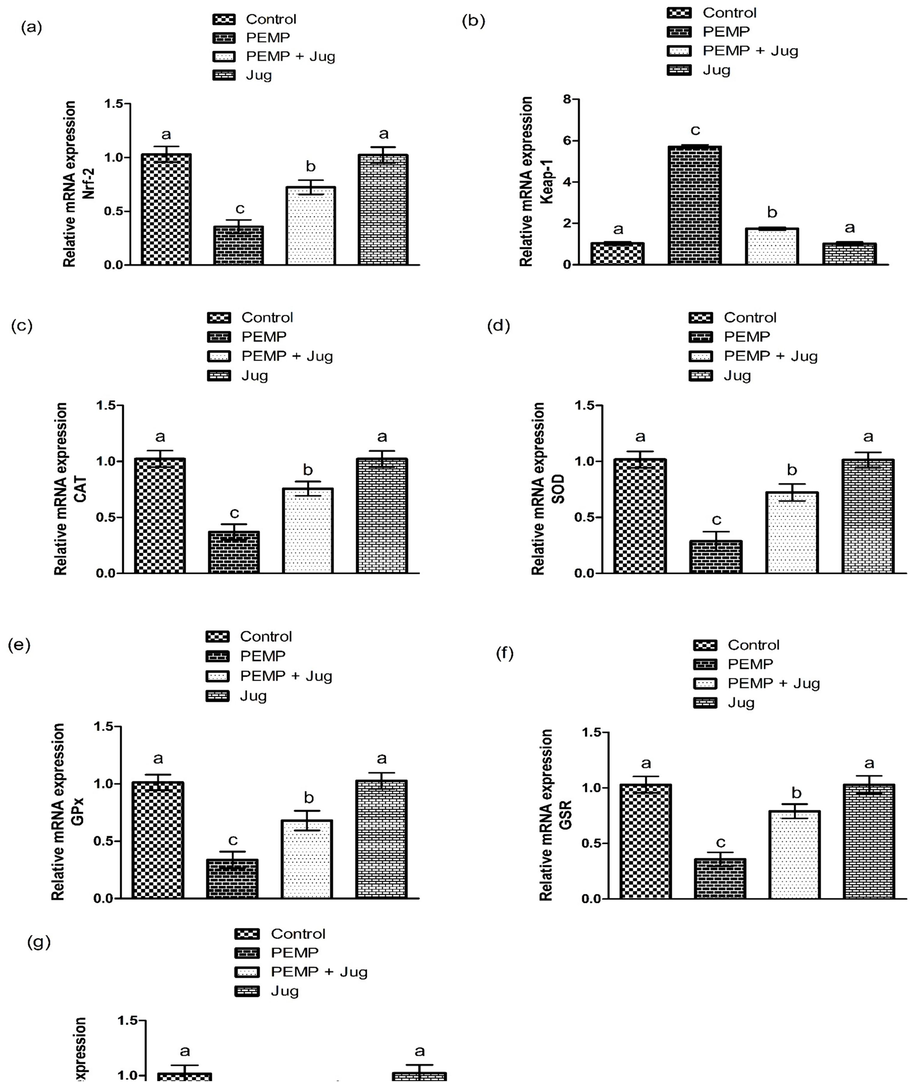

3.1 Jug and PEMP effects on Nrf-2/Keap-1 pathway

PEMP intoxication induced a significant (P<0.05) decrease in Nrf-2 and anti-oxidants expressions, while increasing Keap-1 expression as matched with the control rats. Nevertheless, the administration of PEMP+Jug escalated Nrf-2 and anti-oxidants genes expression and down-regulated the expression of Keap-1. Additionally, Jug alone administered animals presented these expressions close to control animals (Fig. 1).

Effect of PEMP and Jug on the expression of Nrf-2 and Keap-1. Bars are are shown on the basis of Mean ± SEM. Bars with different superscripts are significantly (P<0.05) different from others.

3.2 Jug and PEMP effects on biochemical profile

PEMP exposure showed a substantial (P<0.05) reduction in anti-oxidants activity but there was a noticeable increase was observed in ROS and MDA levels as matched in the control group. Nonetheless, PEMP+Jug co-treatment increase the enzymatic activities of above mention enzymes, while the content of ROS and MDA was decreased in contrast to PEMP induced rats. Additionally, Jug alone supplementation did not show any noticeable difference in the profile of antioxidant/oxidants parameters, when compared with the control group (Table 2). Values are shown on the basis of Mean ± SEM. The values with different superscripts in a row are significantly (P<0.05) different from other groups.

Parameters

Groups

Control

PEMP

PEMP+Jug

Jug

CAT (U/mg protein)

9.32 ± 0.28a

5.03 ± 0.24c

7.77 ± 0.20b

9.36 ± 0.26a

GPx (U/mg protein)

19.03 ± 0.14a

8.77 ± 0.12c

14.96 ± 0.15b

19.07 ± 0.21a

SOD (U/mg protein)

6.97 ± 0.36a

2.56 ± 0.18c

5.39 ± 0.15b

7.08 ± 0.37a

GSR (nM NADPH oxidized/min/mg tissue)

4.39 ± 0.23a

1.49 ± 0.08c

3.38 ± 0.10b

4.43 ± 0.30a

HO-1 (pmoles bilirubin/ mg protein/h)

476.02 ± 9.06a

88.44 ± 6.52c

348.06 ± 14.63b

481.45 ± 12.40a

MDA (nmol/mL)

0.71 ± 0.03c

2.02 ± 0.11a

1.24 ± 0.03b

0.68 ± 0.04c

ROS (U/mg tissue)

0.91 ± 0.04c

7.12 ± 0.24a

1.97 ± 0.09b

0.89 ± 0.04c

3.3 Jug and PEMP effects on inflammatory markers

PEMP intoxication increased the levels of inflammatory markers as compared to the control group. Jug + PEMP treatment notably decreased the level of these markers in contrast to the PEMP-intoxicated group. Nonetheless, the group that received Jug supplementation showed approximately the similar results as in the control group (Table 3). Values are shown on the basis of Mean ± SEM. The values with different superscripts in a row are significantly (P<0.05) different from other groups.

Parameters

Groups

Control

PEMP

PEMP+Jug

Jug

NF-kB (ng/g tissue)

14.19 ± 0.66c

81.25 ± 1.32a

28.76 ± 1.93b

13.99 ± 0.61c

TNF-α (ng/g tissue)

7.93 ± 0.47c

27.75 ± 1.15a

14.25 ± 1.22b

7.76 ± 0.39c

1L-1β (ng/g tissue)

23.30 ± 1.28c

88.71 ± 1.84a

39.96 ± 2.51b

22.95 ± 1.21c

IL-6 (ng/g tissue)

6.31 ± 0.31c

55.88 ± 1.65a

14.54 ± 0.97b

6.28 ± 0.35c

COX-2 (ng/g tissue)

25.33 ± 1.17c

95.42 ± 1.84a

43.36 ± 1.28b

25.13 ± 1.40c

3.4 Jug and PEMP effects on hormonal assay

PEMP treatment significantly (P<0.05) lowered the levels of LH, testosterone and FSH as matched to the control group. The co-administration of PEMP and Jug considerably increased the level of these hormones as compared to PEMP administrated rats. However, the group that received Jug supplementation shows approximately the similar results as in the control group (Table 4). Values are shown on the basis of Mean ± SEM. The values with different superscripts in a row are significantly (P<0.05) different from other groups.

Parameters

Groups

Control

PEMP

PEMP+Jug

Jug

Plasma Testosterone (ng/mL)

4.76 ± 0.04a

2.25 ± 0.04a

110.45 ± 106.89a

4.78 ± 0.04a

LH (ng/mL)

2.46 ± 0.10a

1.18 ± 0.09b

2.11 ± 0.04a

2.50 ± 0.12a

FSH (ng/mL)

3.48 ± 0.08a

1.03 ± 0.09c

2.76 ± 0.06b

3.51 ± 0.09a

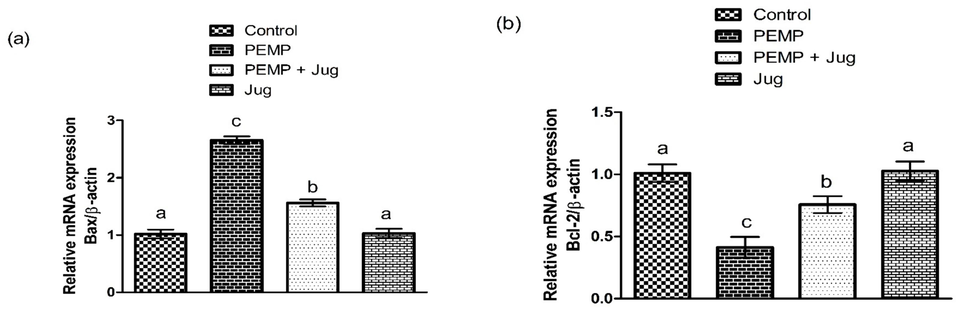

3.5 Jug and PEMP effects on apoptotic proteins

The exposure to PEMP increased (P<0.05) the Bax and Caspase-3 expressions, whereas substantially lowered Bcl-2 expression in contrast with the control group. Jug + PEMP co-administration lowered the augmented Bax and Caspase-3 expressions, while increasing the Bcl-2 expression relative to PEMP intoxicated rats. Jug-only treatment showed the same expression of the abovementioned proteins as in the control rats (Fig. 2).

Effect of PEMP and Jug on the expression of Bax, Bcl-2 and Caspase-3. Bars are are shown on the basis of Mean ± SEM. Bars with different superscripts are significantly (P<0.05) different from others.

Effect of PEMP and Jug on the expression of Bax, Bcl-2 and Caspase-3. Bars are are shown on the basis of Mean ± SEM. Bars with different superscripts are significantly (P<0.05) different from others.

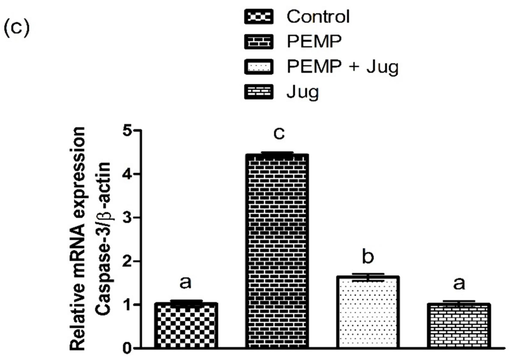

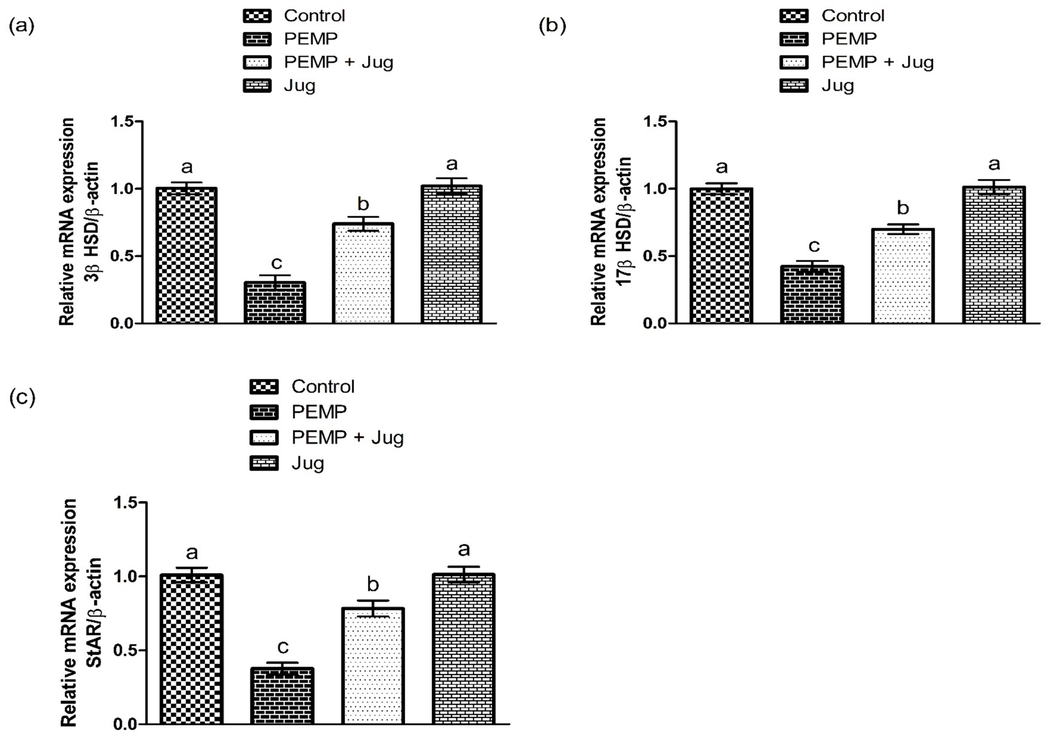

3.6 Jug and PE-MP effects on steroidogenic enzymes

PEMP intoxicated considerably (P<0.05) decreased the expression of 3β-HSD, StAR as well as 17β-HSD as compared to the control group. However, Jug + PEMP treatment increased these expression as compared to PEMP administrated group. However, Jug only treatment depicted similar profile of these enzymes as in the control group (Fig. 3).

Effect of PEMP and Jug on the expression of 3β-HSD, 17β-HSD and StAR. Bars are are shown on the basis of Mean ± SEM. Bars with different superscripts are significantly (P<0.05) different from others.

4 Discussion

In the current study, PEMP exposure downregulated the Nrf-2 and anti-oxidants expression (GSR, CAT, SOD, HO-1 and GPx), whereas increased the Keap-1 expressions. The Nrf-2/Keap-1 signaling pathway is an important antioxidant defense system that promotes an adaptive cellular response to oxidative stress while also play a role in toxicant metabolism and detoxification. The transcription factor Nrf-2 has a key function in regulating both electrophilic stress and oxidative stress (OS). Conversely, Keap-1 interacts with Nrf-2 and inhibits it, and thus controlling its stability (Pintard et al., 2004). OS causes an increase in ROS production, which changes the cysteine residues on Keap-1. This causes Keap-1 to undergo a conformational shift, preventing it from efficiently binding to Nrf-2. Subsequently, Keap-1 liberates Nrf-2, rendering it to undergoing degradation. Because of this, Nrf-2 can build up in the cytosol. When Nrf-2 accumulates, it moves into the nucleus of the cell and attaches itself to anti-oxidant response element, a particular DNA sequence. Various anti-oxidant and detoxifying genes are activated when Nrf-2 binds to ARE (Bellezza et al., 2018). According to Hawkes et al. (2014), Nrf-2 is therefore essential for controlling the induction of antioxidant enzymes. This study found that exposure to PEMP suppressed Nrf-2 expression, while escalating Keap-1 expression, which in turn decreased cytoprotective anti-oxidants expressions. Conversely, the co-treatment of Jug significantly regulated anti-oxidant gene expression by regulating the Nrf-2/Keap-1 signaling pathway.

The oral administration of PEMP significantly dysregulated the antioxidant defense system by decreasing enzymatic activities such as GSR, CAT, SOD, GPx as well as HO-1. Whereas, MDA and ROS concentration was escalated. Antioxidant enzymes are considered a fundamental defense line that shields the DNA, protein and lipids (biomolecules of life) from OS by lowering the formation of ROS (Alvi et al., 2022). Hydrogen peroxide, nitric oxide and hydroxyl radical are the most important oxygen and nitrogen reactive species involved in body impairment (Mijatović et al., 2020). The imbalance between antioxidants and ROS concentration leads to the degradation of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) present in the membrane of sperm (Fois et al., 2018), and it also initiates a self-perpetuating chemical reaction referred as lipid peroxidation (LP). SOD, a free radical scavenger turns oxygen anions (O-) into hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), whereas CAT and GPx transformed H2O2 into hydrogen oxide (H2O) (Aslani and Ghobadi, 2016; Ighodaro and Akinloye, 2018). HO-1 is responsible for the breakdown of heme and regulates cellular homeostasis (Bai et al., 2017). Apart from the intracellular antioxidant defense line, some plant-based remedies such as flavonoids hold hydroxy phenolic groups responsible for their antioxidant activity (Rodríguez De Luna et al., 2020). Jug co-administration with PEMP significantly attenuated the severe damages induced by OS in testes. Our findings coincided with the examination of Wei et al. (2022), who demonstrated that Jug administration alleviated the augmented MDA content and restored the normal anti-oxidant system (CAT, GPx, SOD, GSR and HO-1) activities in the brain cells. Moreover, the ability of Jug to salvage free radicals may be responsible for its antioxidant capacity. Furthermore, Proch́azkov́a et al. (2011) have demonstrated that flavonoids have multiple hydroxyl groups in their chemical structure that contribute to the antioxidant property.

PEMP administration significantly escalated the levels of inflammatory markers. Any cellular instigation activates the inflammatory mediator i.e., NF-κB, which eventually increases IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α level and COX-2 activity (Taniguchi and Karin, 2018). Moreover, up-regulated expression of TNF-α initiates inflammatory responses and apoptosis (Fischer and Maier, 2015). Our outcomes elucidated the remedial role of the Jug responsible for the suppression of inflammatory responses by alleviating the level of inflammatory mediators. Zhang and Xu (2018), illustrated that inactivation of the NF-κB signaling might be the underlying reason associated with the anti-inflammatory potential of Jug. Furthermore our finding are further endorsed by the study of Wei et al. (2022) who reported that Jug supplementation alleviate doxorubicin-induced cognitive impairment in rats by regulating inflammatory responses.

According to our findings, PEMP administration reduced the levels of gonadotropin and androgen hormones (LH, FSH and testosterone respectively). Spermatogenesis is a vital phenomenon that is responsible for the generation of spermatozoa. The indication of a healthy male reproductive tract is associated with the normal production of these hormones. Hypothalamic gonadotrophin-releasing hormones control the liberation of LH and FSH (Khanehzad et al., 2021). LH encourages the activation of Leydig cells found in interstitial space. Activation of Leydig cells triggers testosterone production (O'Shaughnessy, 2014). FSH triggers the proliferation of spermatogonia as well as the Sertoli cells that are present inside the seminiferous tubules (Ramaswamy and Weinbauer, 2014). Ijaz et al. (2022a) evinced that PEMP exposure disrupts the hypothalamus-pituitary–gonadal axis (HPGA) that primarily regulates reproductive functions. However, Jug treatment considerably normalized the hormonal levels. Jug supplementation may avert these hazardous changes in hormonal levels by protecting any damage in HPGA.

PEMP treatment augmented the expressions of apoptotic proteins (Bax and Caspase-3), whereas considerably lowered the Bcl-2 expression. Apoptotic processes or events are regarded as indicator of OS (Ishtiaq et al., 2022). Bax and caspase-3 encourage apoptotic events. Whereas, Bcl-2 (antiapoptotic protein) plays an important role to restrain programmed cell death (Opferman and Kothari, 2018). Thus, the imbalance between these apoptotic and anti-apoptotic proteins is linked to OS produced in rats exposed to PEMP. Moreover, the permeability of the mitochondrial membrane is negatively altered due to a decline in Bcl-2 and an augmentation in Bax, leading to an increase in cytochrome c liberation in cytosol. Elevation in cytochrome c within cytoplasm triggers the stimulation of Caspase-3, the protein that promotes apoptosis (Kaur et al., 2020). The findings of our study predicted that Jug co-administration with PEMP reversed all the alternations in the apoptotic and anti-apoptotic proteins expression. Furthermore, our results are further endorsed by previous research reported that Caspase-3 expression was alleviated in rat’s brain cells supplemented with Jug (Wei et al., 2022).

The treatment of PEMP lowered the expressions of 3β-HSD and 17β-HSD. These enzymes play a vital role to maintain the steroidogenic processes and androgenesis. In steroidogenic events, StAR serves as a transport protein that helps in the shifting of cholesterol to the inner side of mitochondrial membrane (Das et al., 2012). While, steroidogenic (17β-HSD and 3β-HSD) enzymes trigger cholesterol conversion into testosterone hormone (Couture et al., 2020). Thus, downregulation in these enzymes expression in PEMP-administrated animals may cease cholesterol channeling leading to a reduction in the process of steroidogenesis. However, Jug + PEMP co-administration improved steroidogenesis by bringing an elevation in the expression of steroidogenic enzymes. It was also directed from a previous study that the molecular structure of flavonoids is identical to the cholesterol as well as other steroids which might have an impact on the generation of androgens (Martin and Touaibia, 2020). Consequently, it might be the main reason to detect increment in the steroidogenic enzymes followed by Jug + PEMP co-administration.

5 Conclusion

PEMP exposure induced damage in the testes by changing the profile of anti-oxidants and inflammatory indices. The level of hormones, expressions of steroidogenic enzymes and apoptotic/anti-apoptotic proteins were significantly disturbed in PEMP exposed rats. The disturbance in these parameters induced deterioration in the functioning of the reproductive system. While, Jug treatment repaired the above mentioned damages due to its anti-oxidant, anti-apoptotic and anti-inflammatory properties. Collectively, Jug exhibits pharmacological potential to normalize the testicular damage induced by PEMP exposure.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Kaynat Alvi: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization. Ali Hamza: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Methodology, Investigation. Nazia Ehsan: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Moazma Batool: Visualization, Software, Formal analysis, Data curation. Muhammad Zaid Salar: Software, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. Zubair Ahmed: Writing – review & editing, Resources, Funding acquisition. Uman Atique: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Data curation.

Acknowledgement

This work was funded by Researchers Supporting Project number (RSPD2024R1113), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Ameliorative effects of rhamnetin against polystyrene microplastics-induced nephrotoxicity in rats. Pak Vet J. 2023;43(3):623-627.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nephroprotective Effects of Delphinidin against Bisphenol A Induced Kidney Damage in Rats. Pak. Vet. J.. 2022;43(1):189-193.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Studies on oxidants and antioxidants with a brief glance at their relevance to the immune system. Life Sci.. 2016;146:163-173.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Supplemental effects of probiotic Bacillus subtilis fmbJ on growth performance, antioxidant capacity, and meat quality of broiler chickens. Poult. Sci.. 2017;96:74-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nrf2-Keap1 signaling in oxidative and reductive stress. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Mol. Cell Res.. 2018;1865(5):721-733.

- [Google Scholar]

- Purification and characterization of the flavoenzyme glutathione reductase from rat liver. J. Biol. Chem.. 1975;250:5475-5480.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Luteolin modulates gene expression related to steroidogenesis, apoptosis, and stress response in rat LC540 tumor Leydig cells. Cell Biol. Toxicol.. 2020;36:31-49.

- [Google Scholar]

- Taurine protects rat testes against doxorubicin-induced oxidative stress as well as p53, Fas and caspase 12-mediated apoptosis. Amino Acids. 2012;42:1839-1855.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Interrelation of oxidative stress and inflammation in neurodegenerative disease: role of TNF. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev.. 2015;1–18

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of oxidative stress biomarkers in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and therapeutic applications: a systematic review. Respir. Res.. 2018;19:1-13.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Marine microplastics spell big problems for future generations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.. 2016;113:2331-2333.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Use of micro-plastic beads in cosmetic products in Europe and their estimated emissions to the North Sea environment. SOFW J.. 2015;141:40-46.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rhamnetin alleviates polystyrene microplastics-induced testicular damage by restoring biochemical, steroidogenic, hormonal, apoptotic, inflammatory, spermatogenic and histological profile in male albino rats. Hum. Exp. Toxicol.. 2023;42

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hepatoprotective effects of astragalin against polystyrene microplastics induced hepatic damage in male albino rats by modulating Nrf-2/ Keap-1 pathway. J. Funct. Foods. 2023;108:105771

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Regulation of the human thioredoxin gene promoter and its key substrates: a study of functional and putative regulatory elements. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Mol. Cell Res.. 2014;1840(1):303-314.

- [Google Scholar]

- High-throughput spectrophotometric assay of reactive oxygen species in serum. Mutat. Res. Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen.. 2007;631:55-61.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ighodaro, O.M., Akinloye, O.A., 2018. First line defence antioxidants-superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT) and glutathione peroxidase (GPX): Their fundamental role in the entire antioxidant defence grid. Alexandria J. Med. 54, 287-293. Doi.10.1016/j.ajme.2017.09.001.

- Toxic effect of polyethylene microplastic on testicles and ameliorative effect of luteolin in adult rats: Environmental challenge. J. King Saud Univ. Sci.. 2022;34:102064

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chemoprotective effect of vitexin against cisplatin-induced biochemical, spermatological, steroidogenic, hormonal, apoptotic and histopathological damages in the testes of Sprague-Dawley rats. Saudi Pharm. J.. 2022;30(5):519-526.

- [Google Scholar]

- Therapeutic effect of oroxylin a against bisphenol A-induced kidney damage in rats: a histological and biochemical study. Pak. Vet. J.. 2022;42(4):511-516.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Plastic waste inputs from land into the ocean. Science. 2015;347:768-771.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A modified spectrophotometric assay of superoxide dismutase. Indian J. Biochem.. 1984;21:130-132.

- [Google Scholar]

- Molecular mechanism of C-phycocyanin induced apoptosis in LNCaP cells. Bioorg. Med. Chem.. 2020;28:115272

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- FSH regulates RA signaling to commit spermatogonia into differentiation pathway and meiosis. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol.. 2021;19:1-19.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Anthropogenic contamination of tap water, beer, and sea salt. Library Sci. Public. 2018;13:0194970.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Glutathione peroxidase activity in selenium-deficient rat liver. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.. 1976;71:952-958.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25:402-408.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Magee, C.C., Azuma, H., Knoflach, A., Denton, M.D., Chandraker, A., I.Y.E.R, S., Buelow, R and Sayegh, M., 1999. In Vitroandin Vivo Immunomodulatory Effects of RDP1258, a Novel Synthetic Peptide. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 10, 19972005.

- Improvement of testicular steroidogenesis using flavonoids and isoflavonoids for prevention of late-onset male hypogonadism. Antioxidant. 2020;9:237.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The double-faced role of nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species in solid tumors. Antioxidants. 2020;9:374.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Anti-apoptotic BCL-2 family members in development. Cell Death Differ.. 2018;25:37-45.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hormonal control of germ cell development and spermatogenesis. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol.. 2014;29:55-65.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Occurrence and amount of microplastic ingested by fishes in watersheds of the Gulf of Mexico. Mar. Pollut. Bull.. 2015;100(1):264-269.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cullin-based ubiquitin ligases: Cul3–BTB complexes join the family. EMBO J.. 2004;23(8):1681-1687.

- [Google Scholar]

- Estimation of product of lipid peroxidation (malonyldialdehyde) in biochemical systems. Anal. Biochem.. 1966;16:359-364.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Proch́azkov́a, D., Bouˇsov́a, I., Wilhelmov́a, N., 2011. Antioxidant and prooxidant properties of flavonoids. Fitoterapia, 82(4): 513–523.

- Endocrine control of spermatogenesis: Role of FSH and LH/testosterone. Spermatogenesis. 2014;4:996025

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The global odyssey of plastic pollution. Science. 2020;368(6496):1184-1185.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Environmentally friendly methods for flavonoid extraction from plant material: Impact of their operating conditions on yield and antioxidant properties. Sci. World J.. 2020;1–38

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- NF-κB, inflammation, immunity and cancer: coming of age. Nat. Rev. Immunol.. 2018;18:309-324.

- [Google Scholar]

- Protective effect of Juglanin against doxorubicin-induced cognitive impairment in rats: Effect on oxidative, inflammatory and apoptotic machineries. Metab. Brain Dis.. 2022;37:1185-1195.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Microplastic pollution in table salts from China. Environ. Sci. Technol.. 2015;49:3622-13627.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Juglanin ameliorates LPS-induced neuroinflammation in animal models of Parkinson’s disease and cell culture via inactivating TLR4/NF-κB pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother.. 2018;97:1011-1019.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]