Translate this page into:

Morphological, chemoprofile and soil analysis comparison of Corymbia citriodora (Hook.) K.D. Hill and L.A.S. Johnson along with the green synthesis of iron oxide nanoparticles

⁎Corresponding authors. biotechurn@gmail.com (Ayyakannu Usha Raja Nanthini), t.farooq@bangor.ac.uk (Taimoor Hassan Farooq)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Objective

The objective of this research study was to identify the morphological characteristics and essential oil components of Corymbia citriodora (Hook.) K. D. Hill and L.A.S. Johnson grown in two different geographical locations-Kodaikanal and Nashik. A comparative soil analysis was also carried out to detect the soil quality under Corymbia citriodora (C. citriodora) plantation. Green synthesis of Iron oxide nanoparticles from C. citriodora leaf extract has been carried out.

Methods

Hydro-distillation method was used to extract the essential oils from both the species and GC–MS analysis was carried out to detect the chemical components. A comparative morphological analysis was carried out for both the plant specimens while soil analysis from three different places- forest soil, soil under C. citriodora plantation and agricultural field soil was performed. Iron oxide nanoparticles were synthesized by using leaf extract of C. citrodora and its reduction by FeSO4·7H2O solution was found. The structural properties of Iron oxide nanoparticles were studied by UV, X-ray diffraction, FTIR and SEM.

Results

The morphological result showed that both the C. citriodora species had the same characteristics with a slight variation in the bark and leaf colour. The essential oil profile showed citronellol as the major compound in both the species, dI- Isopulegol was found only in C. citriodora from Kodaikanal in more concentration (less than citronellol) while the eucalyptol content was found to be more in Nashik species. For soil analysis it was observed that, even though the soil in the C. citriodora area is more acidic than forest soil, with lower quantities of organic matter and minerals, it also has high levels of organic matter and nutrients, as well as low pH when compared to the soil in agricultural field. The characterisation of iron oxide nanoparticles by UV, FTIR, XRD and SEM confirmed its formation.

Conclusions

The two varieties of C. citriodora from two different locations have not shown wide differences in their morphological characters. The amount of essential oil was observed to be low in Nashik when compared to Kodaikanal, which is due to the geographical area difference. These results showed that the essential oil content varies depending on location, as well as the fact that C. citriodora has little or no negative effects on soil quality. The green method used for synthesis of iron oxide nanoparticles was found to be effective.

Keywords

Corymbia citriodora

GC–MS

Agriculture soil

Forest soil

C. citriodora soil

Iron oxide nanoparticles

1 Introduction

The Corymbia genus is a member of the Myrtaceae family, which is divided into three groups: Angophora, Corymbia and Eucalyptus commonly called as the Eucalyptus group. The Corymbia genus was first included alongwith the Eucalyptusgroup but in 1995, certain studies and new evidence which majorly included genetic variation showed that some Eucalyptus species had more prominence to Angophora genus. Due to this, such Eucalyptus species were then split into the new genus Corymbia (Hill and Johnson, 1995). The species of Corymbia is widely distributed in Australia, while the Eucalyptus group, including the Corymbia genus, has a long history in India. Tipu Sultan, the ruler of Mysore, first planted these species in 1790 at the palace garden near Bangalore, and after sometimes these species was commonly cultivated and used for firewood and paper pulp industry needs (Sundar, 2021).

C. citriodora has long been treasured for its wood and essential oil from its leaves, and this species has well adapted to the agro climatic conditions in the southern belt of India (Singh et al., 1998). It has been reported that Eucalyptus essential oil ranks first in the world trade in which C. citriodora essential oil is the major variety. Different studies have been carried out to study the composition, biological activities and commercial uses of C. citriodora essential oil, but not much has been studied about the influence of climate on essential oil or the effect of C. citriodora growth on the soil properties. A lot of debate has been carried out on the influence of Corymbia along with Eucalyptus on the soil properties with a focus on the possibility of fertility and productivity loss. Some soil qualities are influenced by tree species, according to research (Lugo et al., 1990; Lemma, 2006).Various research and findings have stated the negative impact of Eucalyptus and Corymbia on the soil's characteristics, however the increase in organic carbon content, pH and available nutrients has been observed under young C. citriodora plantation (Prakasarao et al., 1999; Balamurugan et al., 2000).

Various parts of plants like leaf, root, latex, seed and stem are being mostly used for metal nanoparticle synthesis. Nanoparticles produced by plants are more stable, the rate of synthesis is fast and the shape and size of the synthesised nanoparticles are unique when compared with chemically synthesised nanoparticles (Balamurugan et al. (2014)(b)). Synthesis of Iron oxide nanoparticles by using plant extract has been widely reported and this has motivated researchers to synthesise Iron oxide nanoparticles because of their interesting magnetic properties useful for application in biomedical sector, technological areas and agricultural sector (Herelkar et al., 2014).Various works have been reported for the synthesis of Iron oxide nanoaprticles from Eucalyptus leaf extract (Yong et al., 2018; Andrade et al., 2022). C. citriodora has been mostly used to synthesise zinc oxide and manganese nanoparticles (Yuhong et al., 2015; Joao et al., 2022).

An attempt has been carried out in this work to compare and analyse the morphological traits of C. citriodora growing in two different environmental conditions, to determine the effect of regional variation on the essential oil chemical profile as well as quantity. Considering the soil quality factors, an attempt has been made in this work to figure out the effect of C. citriodora growth on the soil properties and also a comparison has been carried out with forest and agriculture field soil. And also the leaf extract of C. citriodora was used for the synthesis of green iron nanoparticles. The findings and studies of this investigation would add detailed information on C. citriodora.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study sites

Two areas with different environmental conditions were selected for the current study. The mountainous area of Kodaikanal, Tamilnadu (10.2381° N, 77.4892° E) and the plain area of Nashik, Maharashtra (19.9975° N, 73.7898° E). Kodaikanal is located at an altitude of 2,133 m, has a monsoon-influenced subtropical highland climate. The temperature is cool throughout the year. On the other hand, Nashik at an altitude of 584 m is in tropical location with mild version of tropical wet and dry climate.

2.2 Sample collection of C. citriodora and soil

The plant specimen(consisting of flowering twig) from Kodaikanal (A) was collected and identified at BSI, Coimbatore, while the plant specimen from Nashik (B) was collected and identified at the Department of Botany, KTHM College in the month of February. The leaf, flower, fruit, and bark characters were all noted down and observed for the morphological characterisation. Soil sampling was carried out from both the areas by standard procedure. Soil was collected from three different areas from both locations (A and B): soil from below the C. citriodora tree, soil from an agricultural field, and soil from a forest (Figs. 1 & 2).

Kodaikanal; 1- Corymbia citriodora (AC); 2- Agriculture field (AA); 3- Forest patch (AF) Latitude-10.26951, Longitude-77.48110 Altitude-2,133 m.

Nashik; 1- Corymbia citriodora (BC); 2- Agriculture field (BA); 3- Forest patch (BF) Latitude-19.94129, Longitude-73.78307 Altitude-584 m.

2.3 Morphological characterisation of plant specimens

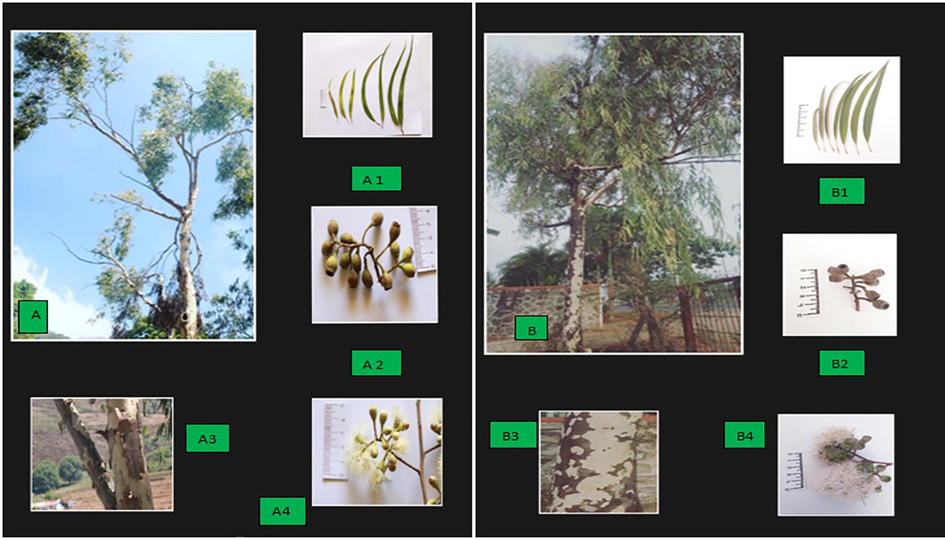

A detailed morphological characterisation was done for both A and B specimens by visual assessment (Lutatenekwa et al., 2020) (Fig. 3 A-A4 & B-B4).

A - Corymbia citriodora (Kodaikanal). A1 - Leaves; A2 - Fruits; A3 - Bark; A4 - Flower and Buds; B - Corymbia citriodora (Nashik). B1 - Leaves; B2 - Fruits; B3 - Bark; B4 - Flower and Buds.

2.4 Extraction of essential oils and GC–MS analysis

The leaves of C. citriodora from both the study areas- Kodaikanal and Nashik were collected and the same day, essential oil was extracted using the hydro distillation process 0.4 kg of freshly cleaned leaves were added to sufficient quantity of water in copper hydro distillation unit. The essential oils were extracted and isolated after 4 h and stored at room temperature in sealed bottles. Both the essential oils were analysed for the identification of metabolites by GC–MS analysis according to Dey and Harborne (1997), method, with considerable modifications. For compound separation and identification, an Agilent 7890B gas chromatography system with an Agilent 5977B MS detector was used (Paul et al., 1999).

2.5 Study of soil properties

All soil samples were chemically analysed at the District soil testing laboratory in Nashik. A pH metre was used to determine the pH by making an aqueous suspension of soil (soil and water in a 1:2.5 ratio) (Jackson, 1967). The electrical conductivity was measured by using an EC meter (Wagh et al., 2013). The organic carbon in soil was measured by standard chromic acid wet oxidation method (Walkley and Black, 1934). The organic matter was found out with the formula, Organic matter (%) = Total Organic carbon × 1.72. The nitrogen content available from the soil was calculated with the alkaline permanganate method (Subbiah and Asija, 1956). The available phosphorous was estimated by Olsen, Bray, and Kurtz extraction methods (Wagh et al., 2013).

2.6 Preparation of C. citriodora leaf extract and the synthesis of iron oxide nanoparticles

The leaves were washed with double distilled water and dried; about 20 gm of leaves were boiled with 500 ml of deionised water. After the sample was cooled, the extract was vacuum filtered and stored in the fridge. A solution of 0.10 M FeSO4.7H2O was prepared with deionised water. After 5 min, 10 ml of the aqueous solution of C. citriodora leaf extract was added to the chemical mixture, and immediately the yellowish colour of the mixture changed into a greenish black colour. After a few minutes, solution of sodium hydroxide was added to the mixture for the nanoparticles to precipitate and settle uniformly. After the addition of sodium hydroxide, the mixture showed black suspended particles. The Iron oxide nanoparticles were separated by carrying out centrifugation for 20 min at 30,000 RPM/hr two times. The Iron Oxide nanoparticles pellet were purified by dispersing in sterile distilled water and again centrifuged 3 times.

2.7 Characterisation of iron oxide nanoparticles

The UV-spectrophotometer analysis characterization of iron oxide nanoparticles were carried out by using UV–visible spectrophotometer (Elico- SL 218 model). The nanoparticles were then subjected to FT-IR spectroscopy measurements to identify the available functional groups responsible for the reduction and capping of Iron oxide nanoparticles (FTIR spectroscopy (PerkinElmer Spectrum). X-ray diffraction (XRD, Bruker D8 Advance model) was carried out to determine the crystalline structure of Iron oxide nanoparticles. SEM analysis was done using software-controlled scanned electron microscope, and the size and morphology were determined by SEM.

3 Results

3.1 Morphological characterisation

While observing the morphological features of the leaves of both A and B species, it was found that the leaf length and width of B species were greater than that of A. The B species leaves were darker green and had a rough texture when compared to the A species. Another difference observed was the size of flowers, the flowers in B species were bigger and more dense than the A species. The A species fruit was bigger than the B species fruit. The rest of the morphological characters like bark, twigs and inflorescence were found to be similar to each other and were not affected by the difference in altitude or climate (Table 1).

S. No.

Characters

A species

B species

1.

Tree

Tall and straight trunk, around 25 m

Tall and straight trunk, around 20 m

2.

Bark

White in colour with prominent brown strips falling out

White in colour mottled

3.

Twig

Woody, cylindrical in older part and quadrangular towards younger part.

Colour- RedWoody, cylindrical in older part and quadrangular towards younger part.

Colour- Dark brown

4.

Leaf

Leaf arrangement-Alternate

Shape-Lanceolate shape in both young and old

Texture- Soft in both young and old

Colour- Light green in older leaves; reddish green in young leaves

Size- 10–26 × 0.9–2 cm

Petiole – Petiolate

Size- 0.8–1.9 cm in length

Colour- Red on outside and light green beneath

Leaf has prominent midrib and reticulate venationLeaf arrangement-Alternate

Shape-Lanceolate shape in both young and old

Texture- Rough in old and soft in young

Colour- Dark green in both old and young leaves

Size- 14–30 × 1–2 cm

Petiole – Petiolate

Size- 1–2.4 cm in length

Colour- Red on outside and light green beneath

Leaf has prominent midrib and reticulate venation

5.

Inflorescence

Position- Axillary

Arrangement- Alternate

Peduncle – 1 cm long

Umble with 3 buds, green in colour, conical operculum

Pedicel length- 0.4–0.6 mm

The flowers were white in colourPosition- Axillary

Arrangement- Alternate

Peduncle – 1 cm long

Umble with 3 buds, green in colour, conical operculum

Pedicel length- 0.3–0.6 mm

The flowers were white in colour

6.

Fruit

Shape- urceolate

Size- 1.5–2 cm long

Colour- Brownish blackShape- urceolate

Size-1–1.5 cm long

Colour- Black

3.2 Essential oils and GC–MS analysis

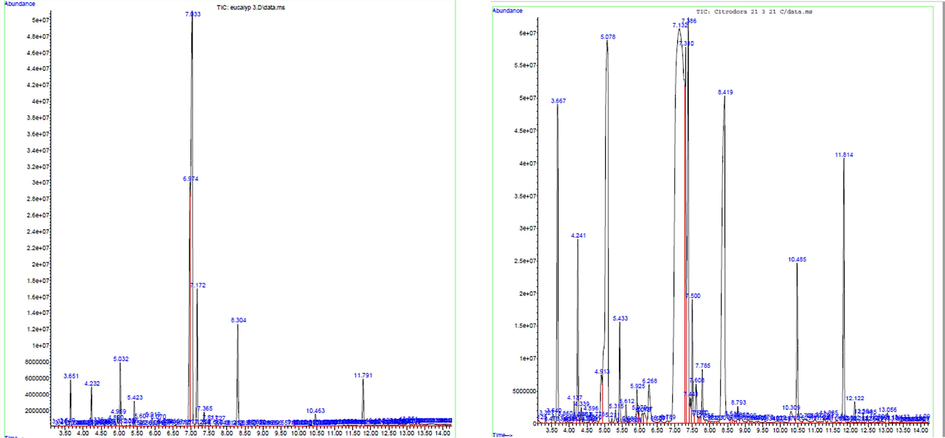

Both A and B essential oil were obtained in dark yellow colour and with strong lemon scented aromatic odour. The yield of A essential oil was 7 ml/4 kg of leaves and for B it was 3.2 ml/4 kg. The difference in the essential oil quantity is due to the geographical location differences. The essential oils of Eucalyptus and Corymbia produce mostly terpenoidal hydrocarbons. The essential oil of A showed 26 compounds, which represents a total percentage of ≥91.86% of the oil profile (Fig. 4). The major compound found was citronellal (49.17%) followed by dI-isopulegol (25.39%), eucalyptol (3.54%), caryophyllene (3.15%) and α-pinene (2.21%). Rest of the compounds were found to be below 2%. Similarly, in the essential oil of B, 27 compounds were shown and represented a total percentage of ≥93.4% of the oil profile (Fig. 4). Citronellal (44.56%) was the most abundant compound followed by eucalyptol (13.30%), cyclohexanol, 5-methyl-2-(1-methylethyl) (12.43%), isopulegol (6.55%), α-pinene (4.51%) caryophyllene (3.30%), 3,6-octadien-3-ol (2.02%) and camphene (2.01%) (Table 2)Most of the compounds in both A and B essential oils were the same, but some minor amount of compounds were absent in either one of the essential oils. Fenchone, cyclohexanol, 5-methyl-2-(1-methylethyl), cis-carveol were absent in essential oil A, while D-limonene, linalool, dI-isopulegol, menthone and oleic acid were absent in essential oil B.

GC–MS analysis of A and B species.

S. No

Compound identified

RT

A

B

1.

α-phellandrene

3.5

0.14

0.16

2.

α-pinene

3.6

2.21

4.51

3.

Camphene

3.8

0.03

2.1

4.

β-pinene

4.2

2.07

0.01

5.

β-myrcene

4.3

0.15

0.17

6.

3-carene

4.7

0.12

0.04

7.

p-cymene

4.8

0.29

0.95

8.

D-limonene

4.9

0.71

–

9.

β-ocimene

5.2

0.08

0.05

10

Eucalyptol

5.0

3.54

13.30

11.

γ-terpinene

5.4

1.34

0.99

12.

(+)-4-carene

5.9

0.57

0.44

13.

Fenchone

5.11

–

0.19

14.

Linalool

6.0

0.38

–

15.

dI- isopulegol

6.9

25.39

–

16.

citronellal

7.0

49.17

44.56

17.

Menthone

7.2

0.09

–

18.

isopulegol

7.3

0.94

6.55

19.

α-terpineol

7.7

0.37

0.67

20.

cyclohexanol, 5-methyl-2-(1-methylethyl)

8.0

–

12.43

21.

cis-carveol

8.5

–

0.10

22.

Citral

9.0

0.01

0.06

23.

citronellic acid

9.8

0.10

0.10

24.

3,6-octadien-3-ol

10.0

–

2.02

25.

2(1H)-naphthalenone

10.6

0.03

0.16

26.

aromadendraane

11.6

0.09

0.30

27.

caryophyllene

11.7

3.15

3.30

28.

naphthalene

12.1

0.16

0.02

29.

α-humulene

12.3

0.19

0.12

30.

alloaromadendrane

12.4

0.17

0.10

31.

oleic acid

13.3

0.37

–

3.3 Classification of the essential oil compounds

Both the essential oil A and B has high concentration of monoterpenes and low concentration of sesquiterpenes (Table 3). The monoterpene concentration in A essential oil (Citronellal and Eucalyptol) is 87.51% and 3.76% of sesquiterpenes, while in B essential oil (Citronellal and Eucalyptol) it is 89.11% of monoterpenes and 3.84% of sesquiterpenes. Cyclic monoterpenes are more in concentration; the major compound citronellol belongs to acyclic alcohol monoterpene group. Two types of ketones and acids are present in each essential oil which contributes to ≤1% of essential oil profile. A slight increased variation of monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes is observed in B essential oil (Low altitude) when compared with the A essential oil (High altitude).

Monoterpenes (Acyclic)

1. β-myrcene

2. β-ocimene

3. citral

4. 3,6-octadien-3-ol

Monoterpenes (Cyclic)

1. α-pinene

2.camphene

3. β-pinene

4. α-phellandrene

5. p-cymene

6. d limonene

7. gamma-terpinene

8. (+)-4-Carene

Monoterpene (Epioxides)

1. eucalyptol

Monoterpene (Acyclic alcohol)

1. linalool

2. citronellal

3. isopulegol

4.di-isoplulgeol

5. terpineol

Monoterpene (cyclic alcohol)

1. alpha-terpineol

2. cis-carveol

3.cyclohexanol,5-methyl-2-(1-methylethyl)

Monoterpene (Bicyclic)

1. 3-carene

Sesquiterpene hydrocarbons

1. aromadendrene

2. α-humulene

3. allo-aromadendrene

4. naphthalene

5. caryophyllene

Ketones

1. fenchone

2. menthone

Acids

1. citronellic acids

2. oleic acid

Non-terpioneodal

2(1H)-naphthalenone

3.4 Effect of C. citriodora species on soil properties when compared with forest soil and agriculture field soil

According to our knowledge C. citriodora affecting the soil parameters has been not studied widely and due to lack of research in this group, our soil parameters study comparison was done with Eucalyptus group (C. citriodora belongs to this group).

3.4.1 Soil pH and EC

The acidity or alkalinity of the soil is expressed by the soil pH. The samples collected in our study reflected a moderately weak acid range of 5.02–6.7. The AA soil showed a 5.02 pH and it was the highest when compared with the rest of the AC (5.92) and AF (6.7). A similar pattern was seen in BA with a 5.45 pH value, which showed the more acidic nature of the soil when compared with BC (5.96) and BF (6.5). In both soil samples, it has been observed that the agriculture soil is more acidic when compared to soil under C. citriodora. The electrical conductivity of aqueous soil extracts determines the total soluble salts. It is also one of the important factors to be noticed while studying soil properties. The EC level in our study was normal (<0.8 dS m−1), with a range of 0.16–0.28 dS m−1. While comparing the AA and BA with AC and BC, a slight variation is observed where agriculture soil shows more EC than C. citriodora soil. Similarly, while comparing AE and BE with AF and BF it is shown that, the C. citriodora soils have fewer EC values (0.17dS m−1 and 0.16 dS m−1). While there is no large variation observed among the soils while observing the EC values (Table 4).

Parameters

AA

(Kodaikanal agriculture field)AC (Kodaikanal C. citriodra soil)

AF (Kodaikanal Forest soil)

BA (Nashik agriculture field)

BC

(Nashik C. citriodora soil)BF (Nashik Forest field)

pH

5.02

5.92

6.7

5.45

5.96

6.5

EC (ds m−1)

0.28

0.17

0.20

0.22

0.16

0.24

OC (%)

2.30

3.28

5.60

2.32

2.80

5.23

OM (%)

3.956

5.64

9.632

3.99

4.81

8.99

N (kg ha−1)

320

356

396

350

373

390

P (kg ha−1)

85

92

98

90

94

97

3.4.2 Organic carbon and organic matter

The result showed that the organic carbons as well as organic matter were highest in both forest soil samples when compared with agriculture soil and Eucalyptus species soils. Organic carbon and organic matter for AF were observed to be 5.60% and 9.63%, while for BF it was 5.23% and 8.99%. Both organic carbon and organic matter were observed to be in greater percentages in AC and BC when compared to AA and BA (Table 4).

3.4.3 Nitrogen and phosphorous

The nitrogen values in our study ranged from 320 to 396 kg ha−1.The nitrogen quantity in AF (396 kg ha−1) and BF (390 kg ha−1) were found to be higher than the other two soils. When compared to AA (320 kg ha−1) and BA (350 kg ha−1), the AC (356 kg ha−1) and BC (373 kg ha−1) were abundant. The available phosphorous was recorded from 85 kg ha-1to 98 kg ha−1. The AF (98 kg ha−1) and BF (97 kg ha−1) had more amount of when compared to agriculture soil and C. citriodora soils. Similar to nitrogen content, the phosphorous content in AC (92 kg ha−1) and BC (94 kg ha−1) was more than AA (85 kg ha−1) and BA (90 kg ha−1) (Table.4).

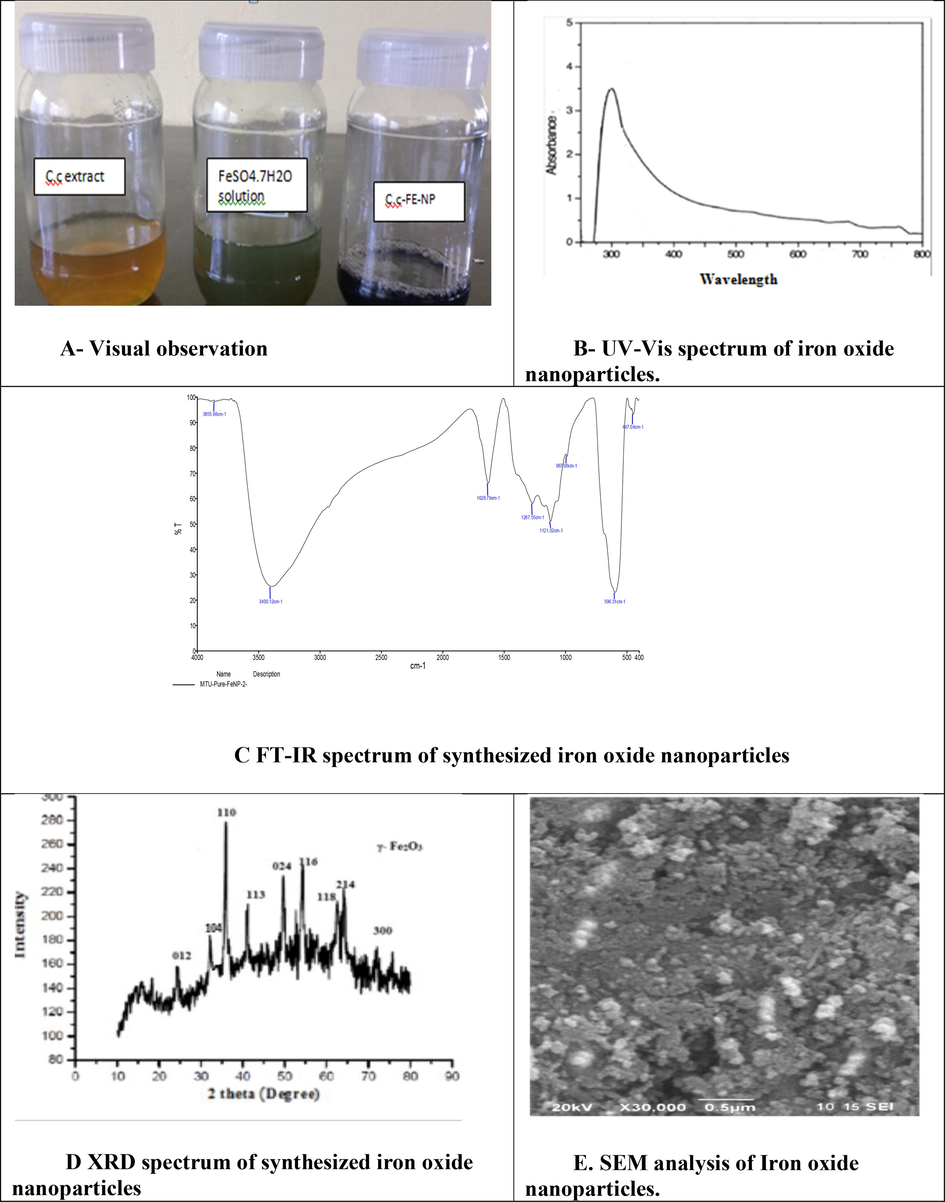

3.5 Characterisation of iron oxide nanoparticles

In the typical synthesis of iron oxide nanoparticles, C. citriodora leaf extract was added slowly into FeSO4.7H2O solution at room temperature. After adding the leaf extract into FeSO4.7H2O solution, within 3 min, a visible colour change was observed, the bluish green colour aqueous solution of FeSO4.7H2O turned to black indicating the synthesis of Iron oxide nanoparticles (Fig. 5A). UV–visible spectroscopy image of the synthesised iron oxide nanoparticles, the colour changes from yellow to greenish black and this indicates the formation of iron oxide nanoparticles. The analysis of UV was done in the range of 200–800 nm and the maximum absorbance was observed at 310 nm region (Fig. 5B). FT-IR spectrum was recorded within the wavelength range 4000–400 cm−1 which ensured the synthesis of iron oxide nanoparticles and also some of the functional groups of the C. citriodora leaf extract. The peak 3400.1 cm−1 indicates –OH stretching, 1628.7 cm−1 indicates H–O–H bond, 1267.55 and 1121.02 cm−1 indicates plant materials and 596.31 cm−1 were assigned to Fe–O stretching (Fig. 5C). The XRD analysis determines the average size, the crystalline nature of the particles and quality of the compound. The XRD pattern displayed nine characteristic 2θ peaks at 25°, 34°, 37°, 42°, 52°, 56°, 64°,66° and 73° marked by their indices (0 1 2), (1 0 4), (1 1 0), (1 1 3), (0 2 4), (1 1 6), (1 1 8), (2 1 4) and (3 0 0) respectively (Fig. 5D) which indicated the formation of iron oxide nanoparticles. The sharp intense peaks showed that the iron oxide nanoparticles synthesised by C. citriodora leaf extract was crystalline in nature. SEM images revealed that the synthesized iron oxide nanoparticles were aggregated as irregular rhombic shapes with panoramic view and range from 50 to 80 nm in size (Fig. 5E).

A - Visual observation; B - UV–Vis spectrum of iron oxide nanoparticles; C - FT-IR spectrum of synthesized iron oxide nanoparticles; D - XRD spectrum of synthesized iron oxide nanoparticles; E - SEM analysis of Iron oxide nanoparticles.

4 Discussions

It has been observed that morphological changes in leaves occur in response to the changing environment, and these changes are readily acquired by the plants (Yang et al., 2015). Sultan, 1995 has reported that in response to the environmental variations plants have the ability to bring out changes in their morphological characters, hence same species plant growing in different locations can show different morphological characteristics. Even though the difference is not large between A and B species, McDonald et al., (2003) studied that the leaf size decreases with increasing altitude, and this is due to precipitation, as well as a reduction in soil nutrient concentration. The micro environment surrounding the Eucalyptus and Corymbia species can bring about changes in the leaf development pattern (Shelly and David, 2000).The difference in the essential oil quantity is due to the geographical location differences. Various exogenous factors like light, precipitation, growing site which includes the latitude and altitude, nature of the soil (chemical properties) etc affects the yield of essential oils (Barra, 2009). A previous study has reported the higher altitude plants produces higher oil yield when compared to lower altitude plants (Singh et al., 2012).Differences in essential oil yield show that the source of seed (area or region) within a species has a significant impact on the success and productivity of forest tree plantings (Missanjo et al., 2014). Kodaikanal has high altitude and more amount of rainfall when compared to Nashik area, due to this difference, it was observed that some compounds (>1% concentration) like, α-pinene, camphene, eucalyptol, isopulegol and caryophyllene increased in quantity with the decrease in altitude, while a few compounds like β-pinene, γ-terpinene and citronellal increased with the increase in altitude. The same result was found by Sanli and Karadogan (2017) when compared with essential oils compounds of Kundmanniaanatolica Hub.-Mor. At different altitudes, chemical components, such as α-thujene, α-phellandrene, β-pinene, β-myrcene and γ-terpinene decreased in quantity with altitudinal increase, while constituents like alpha-pinene increased in quantity with a decrease in altitude. The difference in climatic factors especially, rainfall and humidity may attribute to the presence of compounds like D-limonene, linalool, dI-isopulegol, menthaone and oleic acid in Kodiakanal C. citriodora species while these compounds were absent in Nashik C. Citriodora species.

The essential oils of Eucalyptus and Corymbia produce mostly terpenoidal hydrocarbons. Tobla et al. (2015) reported the major compounds were citronellal (69.77%), citronellol (10.63%), and isopulegol (4.66%) in the essential oil of E. citriodora from Algeria (C. citriodora). Our study showed the presence of 4 acyclic monoterpenes, 8 Cyclic monoterpenes, 1 monoterpene (epioxides), 5 acyclic alcohol monoterpene, 3 cyclic alcohol monoterpene, 1 bicyclic monoterpene, 5 sesquiterpene hydeocarbons, 2 ketones, 2 acids and 1 non-terpioneodal comnpounds. The percentage of sesquiterpene hydrocarbon decreased with an increase in altitude (Talebi et al., 2019). Bilger et al. (2007) have stated that plants at higher altitudes face higher UV-B radiations that havepleiotropic effects on contents of secondary metabolites. Our results agreed with previous findings. Concentrationof terpenes differ in essential oil compositions along the altitude gradient. The sesquiterpenes accounted for the majority of the altitudinal variations in terpene chemistry, with most sesquiterpenes decreasing as altitude increased (Lockhart, 1990).

Soil analysis study showed that even though the difference is not drastic, the acidity of soil in agricultural land can be due to the addition of fertilizer or use of chemical materials. Soil acidity increases with exhausting farming, which is prolonged for many years with the use of fertilisers. The findings matched those of Alemie's, (2009) investigations, which found lower soil pH and values shifting from 3.5 to 4.0 beneath eucalyptus species plantations in Ethiopia's Koga watershed. Liang et al. (2016) reported the same results when compared to nearby agricultural land. The forest soils in both the areas are showing less acidic level when compared to C. citriodora and Agricultural soil. It has been found that forest soils should be mildly acidic in order to maintain a balanced nutrient flow (Leskiw, 1998). The electrical conductivity of aqueous soil extracts determines the total soluble salts. It is also one of the important factors to be noticed while studying soil properties. While there is no large variation observed among the soils while observing the EC values. The high EC values in AA and BA (when compared to AC, BC, AF and BF) can be due to the use of fertilizers or increased amount of irrigation (Visconti and de Paz, 2016).

Soil physical properties are affected by changes in SOC (Soil Organic Carbon) concentration. Organic matter in the form of surface residues can also have a direct impact on water retention by lowering evaporation rates and enhancing water infiltration (Gairola et al., 2012).When compared to agriculture and C. citriodora soil, the high organic carbon and organic matter in forest can be attributed to the extended canopy cover and increased productivity in dense, indigenous (Liang et al., 2016). The forest vegetation is also diverse in species of trees, including grasses and a limited number of animals grazing, which all adds to the increased organic material (Singwane and Malinga, 2012). Both organic carbon and organic matter were observed to be in greater percentages in AC and BC when compared to AA and BA. Despite the fact that our findings contradict a few comparative studies on soil nutrients from exotic Eucalyptus species plantations and other land uses, (Michelsen et al., 1996) similar results have been shown by research conducted out by Ashagrie et al. (2005) and Bekel et al. (2006), who showed that plantation of Eucalyptus species has increased the total soil organic matter after 20 years of plantation.

In most ecosystems, nitrogen is the most limiting nutrient found in soil (Fenn et al., 1998).Our result was found to be in line with Yitaferu et al., 2013 who stated that there was more nitrogen in eucalyptus planted land than other lands. Nitrogen and phosphorous are both linked with the quantity of organic matter, as increased litter falling in the forest and C. citirodora area increases the microorganisms’ breakdown, which generates more nitrogen and phosphorous which increases the organic matter (Alemayhu and Yakob, 2020). A major reason is that the agriculture fields are cultivated and harvested more frequently due to the fact that which they lose a lot of additional nutrients in their topsoil. Although fertilizers are added to increase the nitrogen and phosphorous content in soil, they are actively used up by the crops, causing the soil to become depleted quickly (Alemie et al., 2013).

The degradation of soil by Eucalyptus and Corymbia species is one of the most concerning parts. Studies have reported that these species plantations make the soil unfit for future agricultural uses (Palmberg, 2002). Overall physico-chemical characteristics show that the C. citriodora growth has not affected the soil as compared to the agricultural land. Of the three area soils, the forest soil from both A and B locations had higher quality soil. However, in comparison to the agriculture field soil from both A and B, the C. citriodora soils with significantly higher level of organic matter and comparable pH and nutrient levels suggest that C. citriodora plantation may not always be as detrimental to soil properties as stated in most of the studies. Cunha et al. (2019) has reported that long-rotation nutrient cycling process of C. citriodora is important for maintaining efficiency of the forest site. The soil under C. citriodora has been found to show effect on concentration of P, K, OC, Ca, Mg, Cu, Fe, Mn and B which was found to be reduced however the concentration of N,Z and Sn was found to be increased (Ramamurthy et al., 2016).

One of the most important properties of Iron oxide nanoparticles is to evaluate its optical and photo catalytic activity, UV–Visible spectroscopy is carried out as a preliminary testing to know the above activity. The addition of C. citriodora extract to FeSO4·7H2O solution showed an immediate colour change which determined the formation of Iron oxide nanoparticles (Dadhore et al., 2019). The absorption maxima iron oxide nanoparticles with a peak above 300 nm have been reported by Sravanthi et al. (2016). FTIR displays three strong bonds around 1628.7 cm−1, 1121.02 cm−1 and 596.31 cm−1. The broad peak observed around 596.31 cm−1 (Fe–O stretching) can be due to the presence of organic molecule from the leaf extract on the surface of iron oxide nanoparticles. The other broad peak 1628.7 cm−1 shows H–O–H stretching which indicates phenolic compounds. The weak bond at 447.04 cm−1 and 9570.6 cm−1 may be indicating the presence of unsaturated nitrogen compounds, alkaloids and tannins. The results obtained have been found to be similar with Niraimathee et al. (2016) and Sarvanthi et al. (2016). The XRD pattern and the peaks obtained confirmed the presence of Iron oxide nanoparticles, the crystallinity and the purity of the nanoparticles was denoted by the sharp peaks (Balamurughan et al., 2014 (a)). The surface morphology and size of particles were determined by SEM analysis. The interaction between the iron nanoparticle and its magnetism shows an agglomeration to some extent (Arokiyaraj et al., 2013). Along with green fertilizer use of iron oxide nanoparticles it has also shown antifungal, antibacterial and various other biomedical applications (Bhuvaneshwari et al., 2022).

5 Conclusions

C. citriodora has great commercial value due to its essential oil. The two varieties of C. citriodora from two different locations have not shown a wide difference in their morphological characters. The amount of essential oil was observed to be low in Nashik when compared to Kodaikanal, which is due to the geographical area difference. Temperature, altitude, rainfall, humidity all plays a major role in a plant’s growth and in the synthesis of its secondary metabolites. Citronellal was the major compound found in both the species followed by alpha-pinene. In both species, eucalyptol which is the major compound found in all Eucalyptus species, was found to be in different concentration (lower than citronellal) in both. The difference in essential oil amount between locations as well as the presence and absence of some compounds could be caused by various factors, counting internal and external factors. These are the same factors that influenced oil accumulation in eucalyptus species. The impacts of the Eucalyptus group on soil health remain highly debated among scientists and farmers. Our result indicates that the soil under the C. citriodora is more acidic and has fewer nutrients and organic matter when compared to the forest soils, but the difference is not large. However, there is also evidence from our study that C. citriodora plantations exhibit high organic matter and nutrients in comparison to nearby agriculture fields and there is no increase in acidity. Even though eucalyptus appears to be more favourable than agricultural soil in our study in terms of six soil characters, other ecological effects of C. citriodora like water use and allelopathic have not been carried out. As a result future research needs to be carried out to understand the role of C. citriodora on soil and the rehabilitation of agricultural soil that has been previously degraded by extensive cultivation. While the synthesis of Iron oxide nanoparticles by using green method has been found to be eco-friendly and cost-effective when compared to chemical ways. The prepared iron oxide nanoparticles can be effectively applied as nano-fertilisers without any modification.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by TNSCSCT/DST, reference number TNSCSCT/DST-PRG/TD-AWE/VR/06/2017/3033. The authors would like to acknowledge Sree Balaji Dental College and Hospital, Pallikarani, Chennai, India for providing support and facilities for the completion of this work.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Soil physicochemical properties under Eucalyptus tree species planted in alley maize cropping agroforestry practice in DechaWoreda, Kaffa zone, Southwest Ethiopia. Int. J. Agric. Res. Innovat. Technol.. 2020;10(2):7-14.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Effect of Eucalyptus on Crop Productivity, and Soil Properties in the Koga Watershed, Western Amhara Region, Ethiopia, M.Sc. Thesis. Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University; 2009. p. :60.

- Eco-hydrological impacts of Eucalyptus in the semi humid Ethiopian Highlands: the Lake Tana Plain. J. Hydrol. Hydromech.. 2013;61(1):21-29.

- [Google Scholar]

- Green synthesis of of superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles with eucalyptus globules extract and their applications in the removal of heavy metals from agricultural soil. Molecules. 2022;27(4):1367.

- [Google Scholar]

- Enhanced antibacterial activity of iron oxide magnetic nanoparticles treated with Argemone mexicana L. leaf extract: an in vitro study. Mater. Res. Bull.. 2013;48:3323-3327.

- [Google Scholar]

- Transformation of a Podacarpusfalcatus dominated natural forest into a monoculture Eucalyptus globulus plantation at munesa, Ethipoia: soil organic C, N and S dynamics in primary particle and aggregrate-size fractions. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ.. 2005;106:89-188.

- [Google Scholar]

- (a). Ocimum sanctum leaf extract mediated green synthesis of iron oxide nanoparticles. Spectroscopic and microscopic studies. J. Chem. Pharm. Sci.. 2014;4:201-204.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis of iron oxide nanoparticles by using eucalyptus globulus plant extract. e-J. Surf. Sci. Nanotech. 2014;12:363-367.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of eucalyptus citriodora on the physical and chemical properties of soils. J. Indian Soc. Soil Sci.. 2000;48:491-545.

- [Google Scholar]

- Factors affecting chemical variability of essential oils: a review of recent developments. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2009:1147-1154.

- [Google Scholar]

- Soil carbon sequestration under different exotic tree species in the south western highlands of Ethiopia. Geoderma. 2006;136:886-898.

- [Google Scholar]

- UV screening in higher plants induced by low temperature in the absence of UV-B radiation. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci.. 2007;6:190-195.

- [Google Scholar]

- Iron oxides and their prospects for biomedical applications. Metal oxides for biomedical and biosensor applications. Metal Oxides 2022:503-524.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nutrient cycling in Corymbia citriodora in the state of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Florest. Ambient.. 2019;26(2):e20170204.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and characterization of zero valent iron nanoparticles. In: AIP Conference Proceedings Volume 2100. 2019.

- [Google Scholar]

- Plant Biochemistry (1st edition). London: Academic Press; 1997. eBook ISBN: 9780080525723

- Nitrogen excess in North American ecosystems: predisposing factors, ecosystem responses and management strategies. Ecol. Appl.. 1998;8(3):706-733.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chemical properties of soils in relation to forest composition in moist temperate valley slopes of Garhwal Himalaya, India. Environmentalist. 2012;32:512-523.

- [Google Scholar]

- Systematic studies in the eucalypts. 7. A revision of the bloodwoods, genus Corymbia (Myrtaceae) Telopea. 1995;6(2–3):388-389.

- [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, M. L., 1967.Soil Chemical Analysis. Prentice-Hall of India Pvt. Ltd, New Delhi, 123-126.

- Lemma, B., 2006. Impact of Exotic Tree Plantations on Carbon and Nutrient Dynamics in Abandoned Farmland Soils of Southwestern Ethiopia. PhD dissertation, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Faculty of Natural Resources and Agricultural Sciences, Uppsala: SLU Service/Repro. 42.

- Land Capability Classification for Forest Ecosystem in the Oil Stands Region. Edmonton: Alberia Environmental Protection; 1998.

- Effects of exotic Eucalyptus spp. plantations on soil properties in and around sacred natural sites in the northern Ethiopian Highlands. AIMS Agric. Food. 2016;1(2):175-193.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lockhart, L.A., 1990. Chemotaxonomic relationships within the Central American closed-cone pines. Silvae Genet., 39; 5–6.

- Nutrients and mass in litter and top soil of ten tropical tree plantation. Plant Soil. 1990;125:263-280.

- [Google Scholar]

- A review of plant characterization: First step towards sustainable forage production in challenging environments. Afr. J. Plant Sci. 2020:350-357.

- [Google Scholar]

- Leaf-size divergence along rainfall and soil-nutrient gradients: is the method of size reduction common among clades. Funct. Ecol.. 2003;217:50-57.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparisons of understory vegetation and soil fertility in plantations and adjacent natural forests in the Ethiopian Highlands. J. Appl. Ecol.. 1996;3:627-642.

- [Google Scholar]

- Essential oil yield of Corymbiacitrodora as influenced by harvesting age, seasonal variation and provenance at citrifine plantations in northern Malawi. J. Biodivers. Manage. For.. 2014;3:3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Green synthesis of iron oxide nanoparticles from mimosa pudica extract. Int. J. Environ. Sustain. Develop.. 2016;15(3)

- [Google Scholar]

- Annotated Bibliography on Environmental, Social and Economic Impacts of Eucalypts. FAO; 2002.

- Essential oil of Santlina rosamarinifolia L., ssp. Rosmarinifolia: first isolation of capillene, a diacetylene derivative. Flav. Frag J.. 1999;14(2):131-134.

- [Google Scholar]

- Eucalyptus citriodora-agranomic potentials, distillation technology and soil fertility. Fafai J. 1999:44-47.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of age of plantation and Eason on leaf yield, content and composition of oil of Eucalyptus citriodora Hook. and soil properties in Semi Arid conditions of Karnataka. Res. Crops. 2016;17(1):112-117.

- [Google Scholar]

- Geographical impact on essential oil composition of endemic Kundmanniaanatolica Hub-Mor (Apiaceae) Afr. J. Trad. Complement. Altern. Med.. 2017;14:131-137.

- [Google Scholar]

- Influence of light availability on leaf structure and growth of two Eucalyptus globules ssp. Globules provenances. Tree Physiol.. 2000;20(15):1007-1018.

- [Google Scholar]

- Production potential of aromatic crops in the alleys of Eucalyptus citriodora in semi-arid tropical climate of South India. J. Med. Arom. Plants Sci.. 1998;20:749-752.

- [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of in vitro antioxidant activity of essential oil of Eucalyptus citriodora (lemon-scented Eucalypt; Myrtaceae) and its major constituents. LWT-Food Sci. Technol.. 2012;48:237-241.

- [Google Scholar]

- Impacts of pine and eucalyptus forest plantations on soil organic matter content in Swaziland -Case of Shiselweni forests. J. Sustain. Dev. Afr.. 2012;14:137-151.

- [Google Scholar]

- Green synthesis and characterisation of Iron oxide nanoparticles using Wrightia ticctoria leaf extract and their antibacterial studies. Int. J. Curr. Res. Acad. Rev.. 2016;4:30-44.

- [Google Scholar]

- A rapid procedure for the estimation of available nitrogen in soils. Curr. Sci.. 1956;25:259.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phenotypic plasticity and plant adaptation. Acta Bot. Neerlandica. 1995;44(4):363-383.

- [Google Scholar]

- A Comparative study of the chemical composition of the essential oil from Eucalyptus globulus growing in Dehradun (India) and around the world. Orient. J. Chem.. 2021;32(1):331-340.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of altitude on essential oil composition and on glandular trichome density in three Nepeta species (N.sessilifolia, N. Heliotropifolia and N. Fissa) Mediterr. Bot. 2019

- [Google Scholar]

- Essential oil of Algerian Eucalyptus citriodora: chemical composition, antifungal activity. J. Mycol. Med. 2015:128-133.

- [Google Scholar]

- Electrical conductivity measurements in agriculture: the assessment of soil salinity. In: New Trends and Developments in Metrology. InTech; 2016.

- [Google Scholar]

- Wagh, G.S., Chavhan D.M., Sayyed, M.R.G., 2013. Physico-chemical analysis of soils from Eastern part of Pune city. Univ. J. Environ. Res. Technol., 3(1), 93-99.

- An examination of the Degtjareff method for determining soil organic matter and a proposed modification of the chromic acid titration method. Soil Sci... 1934;40:233-243.

- [Google Scholar]

- Leaf form-climate relationships on the global stage: an ensemble of characters. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr.. 2015;24:1113-1125.

- [Google Scholar]

- Expansion of Eucalyptus woodlots in the fertile soils of the highlands of Ethiopia: Could it be a treat on future cropland use? J. Agric. Sci.. 2013;5(8):97-103.

- [Google Scholar]

- The formation of iron nanoparticles by Eucalyptus leaf extract and used to remove Cr (VI) Sci. Total Environ.. 2018;627:470-479.

- [Google Scholar]

- Green biosynthesis and characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles using Corymbia citriodora leaf extract and their photocatalytic activity. Green Chem. Lett. Rev.. 2015;8(2):59-63.

- [Google Scholar]