Translate this page into:

Synthesis of silver nanoparticles from marine bacteria and evaluation of antimicrobial, antifungal and cytotoxic effects

⁎Corresponding author at: Department of Biosciences, MES College, Marampally, Aluva, Kerala, India. nishap@mesmarampally.org (Nisha Pallath)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background

Marine bacteria, a relatively untapped resource, have shown potential for synthesizing nanoparticles with distinct properties.

Methods

The AgNPs were synthesized by using the marine bacteria Planococcus maritimus MBP-2 as a reducing and capping agent. The nanoparticles produced were characterized by UV–Vis spectroscopy, TEM and FTIR. The Planococcus maritimus MBP-2 synthesized AgNPs adhered antibacterial activity against selected both gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus cereus, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumonia, and antifungal such Aspergillus niger, Aspergillus flavus, Penicillium commune and Penicillium digitatum. and the cytotoxic effect of Dalton’s Lymphoma Ascites (DLA) cell lines.

Results

The formation of AgNPs by bacteria was confirmed visually by a shift in color of the solution and the presence of UV-absorption maxima at 440 nm. The TEM images revealed spherical and cubic structures, with an average size of 24.9 nm. FTIR analysis confirmed the presence of some functional groups by showing peaks at 3330 and 1636 cm−1. The AgNPs exhibited minimal antibacterial activity except P. aeruginosa. (11 mm). Whereas, inhibiting the growth of the fungi belonging to genus Aspergillus than to Penicillium. Also, in vitro cytotoxicity of AgNPs was evaluated using Dalton’s Lymphoma Ascites (DLA) cell lines. The percentage of cell death was maximum (95.4 ± 2.16) at 20 µg/mL, indicating an excellent cytotoxic efficiency of AgNPs against DLA cells from the peritoneal cavity of the tumor-bearing mouse.

Conclusion

This study suggests that Planococcus maritimus MBP-2 bacteria-mediated AgNPs can effectively be used as a potential biomedical agent.

Keywords

AgNPs

Pigment-producing marine bacteria

Planococcus maritimus

Antimicrobial

Antifungal

Cytotoxicity

1 Introduction

Nanotechnology has offered numerous attractive route of research, offering a specific structures and wide-ranging bids in various fields, such as pharmaceutical, biomedical, agriculture, environmental care, textile, and food [Salem et al., 2022; Caruthers et al., 2007]. Nanosized particles or molecules are promising alternatives for the treatment of several diseases, due to their characteristics such nano-dimension, large surface, optical density, electrical conductivity, high carrier capacity and high reactivity [Lal and Uthaman, 2021]. These special features are useful to control different characteristics of drugs or biomolecules, as an agent to maintain and control several processes, including solubility and blood pool retention time, which enhances controlled release and specific site-targeted delivery [Caruthers et al., 2021].

Ag gained importance at nanoscale level. Ag ultra-sized particles have sizes from 1 to 100 nm and unique morphologies and characteristics [Firdhouse and Lalitha, 2015; Devanesan, et al., 2018]. Therefore, they have been exploited for numerous applications in biomedical field, as antibiotics, antioxidants anti-cancerous and anti-inflammatory agents [Haider and Kang, 2015; Oves et al., 2022].

Several methods have been employed to synthesize Ag nanoparticles (AgNPs). Various physical forces can be used to synthesize AgNPs from bulk material to powder and then to nanostructures [Sobi et al., 2022; Suriyakala et al., 2022]. Even though, the synthesis of AgNPs has few disadvantages in term of large space, time and energy consuming to achieve the target [Iravani, et al., 2014]. Chemical methods employ agents, like glucose, ascorbate, ethylene glycol, citrate, hydrazine, sodium borohydride, or other organic compounds to reduce Ag+ into Ag0 [Goulet and Lennox, 2010]. Additionally, capping agents, such as chitosan, polyethylene glycol (PEG), cellulose, polymers, etc., are used to avoid agglomeration and oxidation of nanoparticles [Pillai and Kamat, 2004].

Considering the disadvantages of physical and chemical methods, the synthesis of AgNPs through biogenic way is getting the interest of many researchers. Biological entities, like plant extracts and microorganisms, have been explored as valuable alternative to other means of synthesis of nanoparticles. They have many advantages, such as easy, non-toxic, ecofriendly, yet producing stable and high-quality nanoparticles, which are compatible with living beings [Naganthran et al., 2022]. The plant parts contain numerous active components, which are involved as synergetic effects, leads to improve the therapeutic value [Verma et al., 2019]. The phytochemical constituents, such as phenolic and flavonoids groups, etc., may act as a capping and reducing agents [Pradeep et al., 2022]. AgNPs from Boswellia carterii resulted able to inhibit the growth of gram- and gram-negative microbial pathogens [Al-Dahmash, et al., 2021].

In the formation of metal-based nanoparticles using microorganisms, the metal ions first resulted attached to inside the microbial cells. The metal ions became reduced into metal elements through the presence enzymes [Ghosh et al., 2021]. Biosynthesis of nanoparticles using microorganisms have been demonstrated by exploiting bacteria, fungi and algae. Naganthran et al. interpreted that the intracellular components in the bacterial extract reduce the Ag+ ions into Ag nanoparticles [Naganthran et al., 2022]. In fact, several bacteria, such as Bacillus cereus [Sunkar and Nachiyar, 2012], Pseudomonas stutzeri AG259 [Klaus et al., 1999], Lactobacillus plantarum TA4 [Mohd Yusof et al., 2020], K. pneumonia [Saleh and Khoman Alwan, 2020], Streptomyces albidoflavus [Prakasham et al., 2012] were used to synthesize AgNPs intra-and extracellularly and proved its potential against pathogenic bacteria, fungi, virus and cancer cells. The AgNPs synthesized from Bacillus methylotrophicus exhibited enhanced fungal activity against Candida albicans [Wang et al., 2016]. Pseudomonas indica mediated AgNPs effectively performed against mucormycosis disease causing fungi [Salem and Fouda, 2021]. Sriram et al. demonstrated the efficiency AgNPs produced from bacterial cells, as an antitumor agent [Sriram et al., 2010]. The authors claimed the less hemolystic properties using Shewanella sp. ARY1 in the synthesis of AgNPs. The results encouraged the low dose 8 μg/mL with biocompatibility for mice erythrocytes assay [Mondal et al., 2020]. Another study reported photocatalytic properties of Streptomyces tuirus strain-based synthesis of AgNPs. It has proven the better photocatalytic activities such 71.3 % for methylene blue dye under sunlight irradiation [Mechouche, et al., 2022].

The aim of the present study was to synthesize AgNPs using marine bacteria as a source of reducing agent. Planococcus maritimus MBP-2 -AgNPs evaluated activities of gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria and antifungal and cytotoxic effects. The Marine Bacteria Planococcus maritimus MBP-2 mediated synthesized AgNPs shows excellent antifungal effects, good antimicrobial and cytotoxic effects are observed.

2 Materials and methods

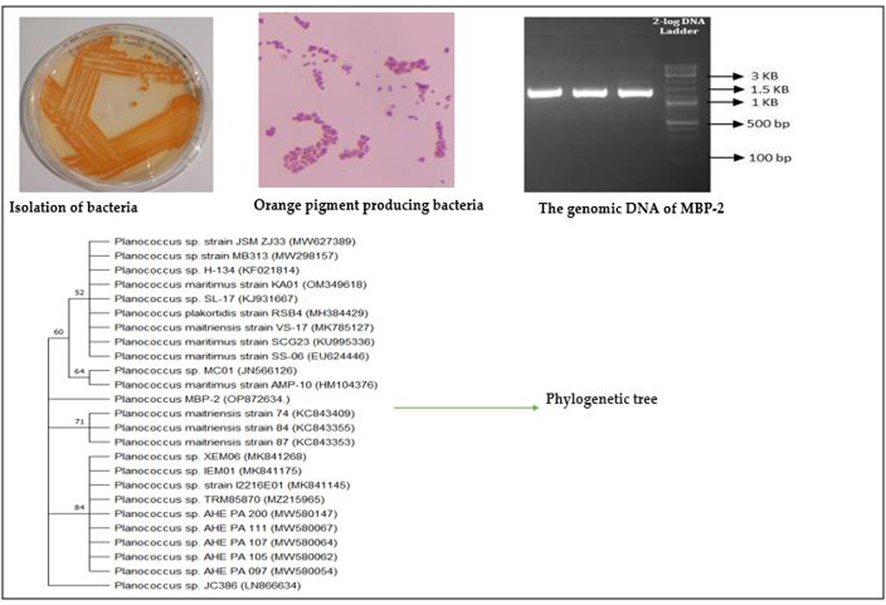

Sample process

Marine samples were collected by scraping the boat hull from Cochin Port in Kerala, India. Bacterial strain was isolated by standard plate dilution method from scarping hull using nutrient agar, NaCl, peptone and yeast extract and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. The growth bacteria were confirmed and identified (Planococcus maritimus MBP −2) through 16S rRNA sequence analysis using universal standard primers 27F and 1492R and compared online using BLAST [Akter et al., 2018]. Then the gene sequence obtained was submitted to Gene Bank, NCBI for further confirmation of the strain (GenBank accession No– OP872634) [Nisha et al.,2023]. The pure culture of bacteria was kept at 4 °C for further studies.

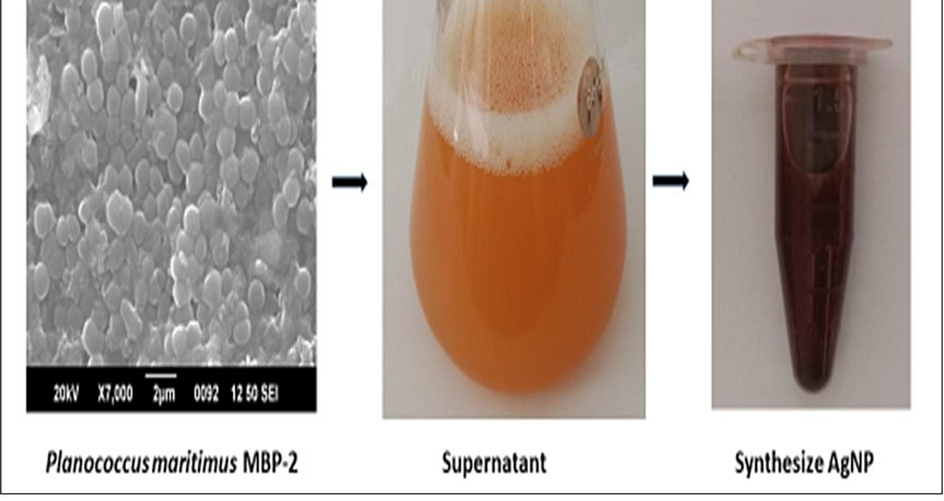

Preparation of bacterial supernatant

The bacterial suspension was prepared using nutrient broth at 37 °C for 24 h, the pure culture the inoculation loop full of Planococcus maritimus MBP-2 culture and incubated in rotary shaker at room temperature for 24–48 h. The culture media was centrifuged at 10000 rpm for 10 min, the process was repeated thrice and the pre filtered to remove particulate material from the sample and separated as a pellet. The bacterial supernatant was stored 4 °C and used for nanoparticles synthesis.

Synthesis of AgNPs

3 mM silver nitrate (AgNO3) solution was prepared by dissolving 0.91 g of AgNO3 in 180 mL of double distilled water and covered with aluminum foil to prevent the photo oxidation of the solution. The separated supernatant of Planococcus maritimus MBP-2 culture was used for the synthesis of silver nitrate nanoparticles (AgNPs). 180 mL of AgNO3 solution was mixed with 20 mL of bacterial supernatant, the mixture was placed into orbital shaking incubator with a rotation speed 100 rpm at room temperature for 24 h. The colour changes was occurred from clear to brownish colored solution visually noticed. In this process, the bacterial supernatant acts as reducing and capping agents as presence of several microbial enzymes. Then the solution along with AgNPs was collected by high speed centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 10 min. The process was repeated thrice to remove any other substances for purity and collected nanoparticles were dried and grinded to make a powder form. This AgNPs were further used for characterization and biological application studies.

Characterizations

UV–Vis spectroscopy is the widely used technique to characterize and confirm the presence of reduced Ag ions as AgNPs and measured for absorbance ranging from 250 to 700 nm using UV–visible spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV 1800, Japan). The size and shape of AgNPs were measured by Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) JEOL, Tokyo, Japan. TEM images were obtained using FE-TEM at an accelerating voltage of 300 kV. The samples for TEM were prepared by placing the nanoparticles on a copper grid containing carbon film. The functional groups present in the bacterial-mediated AgNPs were analyzed with Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan).

Antibacterial activity

The antibacterial activity by following agar well diffusion assay method [Perez, 1990] against standard bacterial strains such as S. aureus, B. cereus, K. pneumonia, P. aeruginosa and E. coli. The bacterial strains were inoculated into peptone broth and incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. Solidified Muller-Hinton Agar (MHA) plates were prepared and the broth culture of each bacterial strains was spread using sterile cotton swab. The wells were cut by using a sterilized gel puncture and loaded with 50 µL of AgNPs suspension at a concentration of 1 µg/mL, prepared by suspending 50 µg synthesized AgNPs in 50 µL sterile distilled water. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24–48 h. Then the zone of inhibin was examined on the plates, which appear as a clear area around the well. A well loaded with sterile distilled water was served as negative control.

Antifungal activity

The antifungal activity of bacteria-mediated AgNPs was assayed by a well diffusion method using different fungal pathogens, such as A. niger, A. flavus, P. commune and P. digitatum. Pre-inoculum was prepared by inoculating the pathogenic culture separately in Sabouraud Dextrose broth and incubated at 37 °C for 2–6 h. Solidified Sabouraud Dextrose Agar (SDA) plates were prepared and the pre-inoculum of fungal cultures was spread on the plate using sterile cotton swab. Wells were cut on the plate and added with 50 µL of AgNPs suspension, at a concentration of 1 µg/mL. The wells with sterile distilled water was used as negative control. The zone of inhibition of pathogenic fungi was measured in millimeter after incubation of plates for 3–4 days at 27 ± 2 °C.

In vitro cytotoxicity assay

Cell lines

The AgNPs against tumor cells were studied by in vitro cytotoxicity assay using Dalton’s Lymphoma Ascites (DLA) cell lines obtained from Pune, India. The cytotoxic study experiments followed by [Sriram et al., 2010].

Trypan blue exclusion method

Briefly, viability of DLA cells was assessed by Trypan blue exclusion method [Shylesh and Nair, 2005]. The viable cell suspension (1x106 cells in 0.1 mL suspension) was added to the tubes containing Planococcus maritimus MBP-2, AgNPs, ranged from 0.25 to 20 µg/mL and total volume 1 mL using PBS solution. Without Planococcus maritimus MBP-2, AgNPs mediated consider as a control. Then, assay mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 3 h. Furthermore, the cell suspension was mixed with 0.1 mL of 1 % Trypan blue and kept for 2–3 m and loaded on a haemocytometer. The cell attached to the dyes it become blue as consider dead cell whereas without colour is live cells The experimental data was performed one- way ANOVA and mean and SD (P < 0.05).

3 Results

The marine bacteria Planococcus maritimus MBP-2 identified by complete sequence of 16S rRNA and phylogenetic tree was used to identify the relationship to the specific strains as reported supplementary Fig. 1. In addition, the biochemical analysis was carried out, as reported in Table 1. --negative reaction, + positive reaction

Sl. no

Biochemical test

Result

1

Indole

–

2

Methyl red

–

3

Vogues Proskeaur

–

4

Citrate

–

5

Triple sugar iron

–

6

Urease

–

7

Glucose

–

8

Lactose

–

9

Sucrose

–

10

Maltose

–

11

Catalase

+

12

Oxidase

–

A shift in the color of the reaction mixture was the initial indication of the obtained synthesis of AgNPs (Fig. 1). Later, the color of the mixture changed from light orange to dark brown color within few h of incubation and the intensity of color increased with the increase in the incubation time, due to bio-reduction of Ag+ ions to Ag0.

The process of green synthesis of AgNPs using marine bacteria Planococcus maritius MBP-2. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

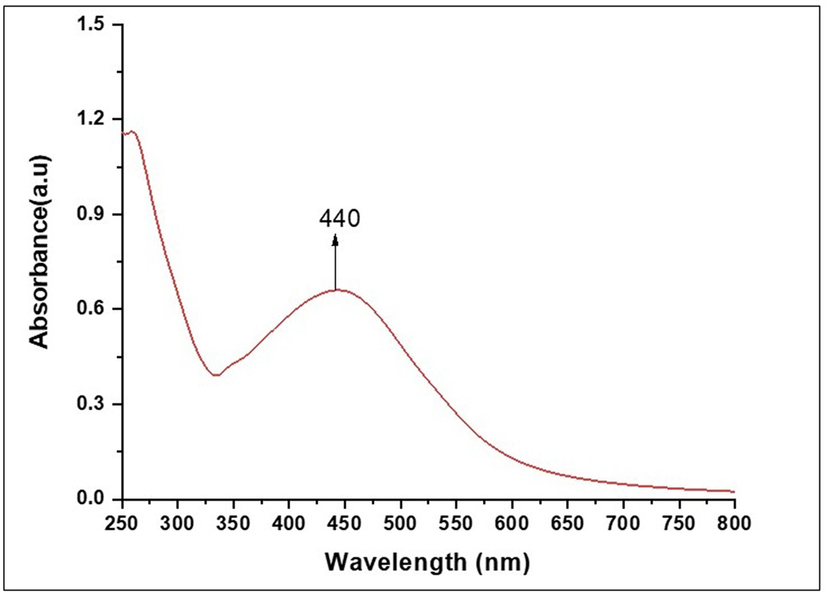

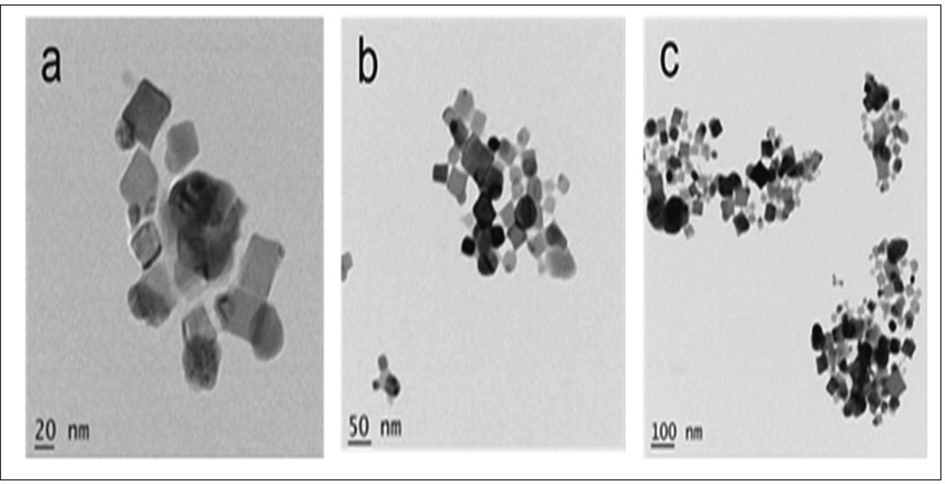

The formation of silver nanoparticles was confirmed by UV–Vis spectroscopy. In the absorbance spectrum, AgNPs showed maximum surface plasmon resonance. (SPR) at 440 nm, which was attributed to the general feature of AgNPs (Fig. 2). The UV–Vis spectral analysis of AgNPs suspension showed a narrowing spectrum with band at 440 nm, indicating the synthesis of AgNPs of smaller size, with a spherical to cubic shape. TEM analysis was used to prove the morphological characterization of synthesized AgNPs with a different magnification such 20 nm to 100 nm (Fig. 3.(a-c)). The TEM images showed that extracellular biosynthesized nanoparticles were well dispersed and spherical to cubic shaped. This is an evidence for synthesized using Planococcus maritimus MBP-2 may fall within size range 100 nm. The average particle diameter estimated by TEM is 24.9 nm. All the magnifications are spherical and few are non- spherical shapes. The smaller size of the AgNPs (less than 100 nm) attached with high surface particular matter and slowly released the silver cations and higher effect as compared to the larger size NPs.

UV–Visible absorbance spectra of silver nanoparticles synthesized by Planococcus maritius MBP-2.

TEM micrographs of silver nanoparticels synthesized by Planococcus maritimus MBP-2. The micrographs were given at three different magnifications: (a) 20 nm; (b) 50 nm and (c) 100 nm.

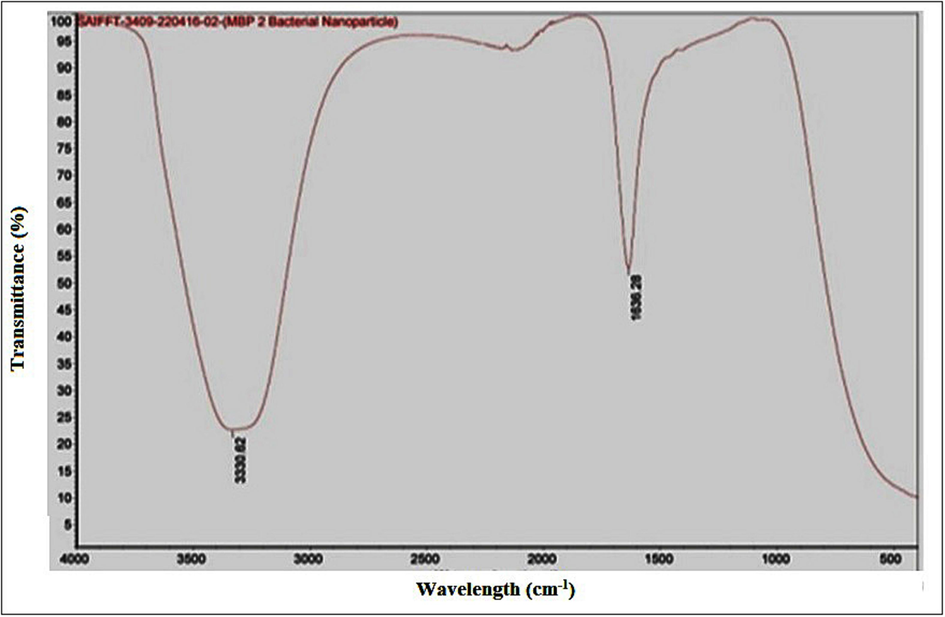

In the FTIR spectrum of AgNPs (Fig. 4), the peak at 3330.62 cm−1 was assigned that, the peaks in between 3200 cm−1 to 3600 cm−1 is the presence of O–H stretching of hydroxyl group and –NH2 amines and 1636.28 cm−1 to amide 1 protein groups. Major peaks in the regions of 1700–1500 and 3500–3300 cm−1 confirmed the presence of carbonyl, carboxyl and hydroxyl groups at the surface.

FTIR spectra of silver nanoparticles synthesized by Planococcus maritimus MBP-2.

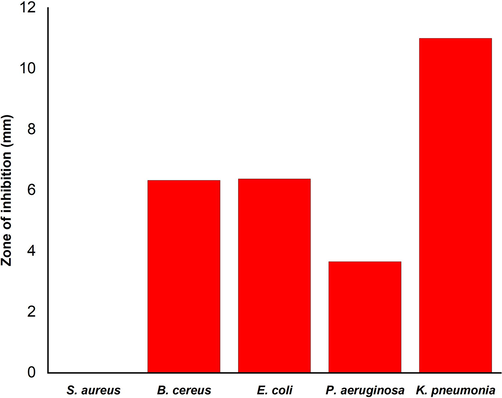

Antibacterial efficiency of AgNPs synthesized by Planococcus. maritimus MBP-2 was investigated against both gram positive (S. aureus and B. cereus.) and gram negative (E. coli, P. aeruginosa and K. pneumonia.) bacteria by agar well diffusion method. Silver nanoparticles at the volume of 50 µL/mL showed different antibacterial effects on all tested bacterial strains (Fig. 5). The highest zone of inhibition was achieved for P. aeruginosa. (11 mm). Whereas, B. cereus and E. coli the zones of inhibition were 6.33 mm and 3.66 mm for K. pneumonia., respectively. Inhibition of bacterial growth around the well was due to the slow release of diffusible compounds, i.e. AgNPs. No inhibition zone was revealed for S. aureus swabbed plate, indicating a strong resistance nature of bacteria. In the last case, the concentration of nanoparticles added may not be sufficient to inhibit the growth. Also, no limitation of cell growth was observed in control, where the wells contained only sterile distilled water without nanoparticles.

Antifungal activity of silver nanoparticles synthesized by Planococcus maritimus MBP-2.

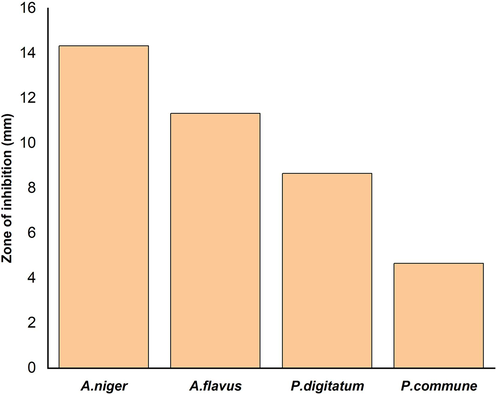

The antifungal activity of AgNPs was assayed against Aspergillus niger, Aspergillus flavus, Penicillium commune and Penicillium digitatum using agar plate well diffusion method. Growth inhibition was observed after 24 h on plates loaded with 50 µL of AgNPs. Nanoparticles were found to be effective in inhibiting the growth of all the fungus tested and the highest efficiency was observed against Aspergillus group compared to Penicillum group (Fig. 6). The diameter of zone of inhibition was highest in A. niger (14.33 mm), followed by A. flavus (11.33 mm) whereas, the Penicillum group activities were 8.66 mm in P. digitatum, while it was 4.66 mm in P. commune. Based on the obtained results exhibit the minimal quantity of AgNPs have highly potential against tested fungal pathogens.

Effect of silver nanoparticles synthesized by Planococcus maritimus MBP-2 on different fungal pathogens.

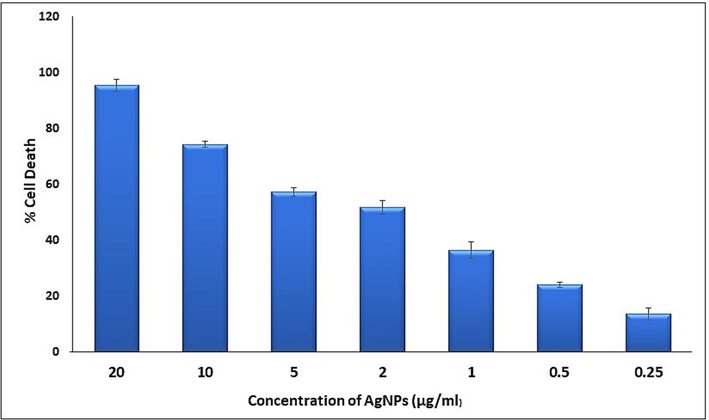

The effect of AgNPs on viability of tumor cells was determined by Trypan blue exclusion assay using DLA cells. The Planococcus. maritimus MBP-2 mediated AgNPs were able to reduce the viability in a dose-dependent 0,25, 0.5,1, 2, 5, 10 and 20 µL/mL manner (Fig. 7). After 3 h of assay, the AgNPs were found to be cytotoxic to DLA cells at concentrations of 2 µg/mL and higher. Silver nanoparticles at 2 µg/mL recorded 52 % of cell death of the initial level and maximum cell death 95 % was recorded at 20 µg/mL. The small size of Planococcus. maritimus MBP-2 facilitated AgNPs can easily penetrate inside to cell, and interact with cellular structures. The biomolecules are support to increase the ROS lead to an apoptosis. Different concentrations AgNPs with obtained results are shown in Table 2.

The effect of different concentrations (0.25 to 20 µg/mL) of AgNPs synthesized by Planococcus maritimus MBP-2 on tumor cell viability.

S. no

Different Con. AgNPs

Live cells

Dead cell

Total no. cells

SD

% Cell Death

1

0.25

87.75

13.75

101.5

2.162

13.6 ± 2.16

2

0.5

73.25

23.25

96.5

1.004

24 ± 1

3

1

67.75

38.75

106.5

2.962

36. 3 ± 2.96

4

2

52.5

56

108.5

2.503

51.6 ± 2.6

5

5

46.75

63.5

109.5

1.582

57.3 ± 1.58

6

10

26.75

77

103.75

1.126

74.2 ± 1.13

7

20

4.75

98.25

103

2.16

95.4 ± 2.16

4 Discussion

There are numerous marine microbial sources in the Ocean, the isolated bacteria Planococcus maritimus MBP-2, from boat hull as a probiotic bacterium. The bacteria involved in capping reducing agents leads to formation of small size of nanoparticles by reductase enzymes. The enzyme catalases were produced by Planococcus maritimus MBP-2 (Table 1) are plays a major role in defense mechanisms such oxidative stress. The Previous report, the Streptomyces strains contain typical catalases without aggregations are protects them from toxic substances and also several secondary metabolites production with elucidated an enriched biological activity [Yuan et al., 2021]. The synthesized AgNPs from bacteria has numerous biological applications including antimicrobial, antifungal, antitumor and antioxidant properties. Thus, the present study. As mentioned by Thomas et al., intracellular synthesis involves synthesis of nanoparticles from wet bacterial biomass and requires additional steps for purification of nanoparticles [Thomas et al., 2014]. Extracellular synthesis of nanoparticles involves a single step process and avoids additional steps to purify the nanoparticles [Huq and Akter, 2021]. In this study, to make AgNPs the extracellular process was used. The mechanism of AgNPs by bacteria has been reported that the Ag + ions are first surrounded on the surface cells and the trapped ions are further reduced to Ag0 forming AgNPs by NADH related enzyme [Tamboli and Lee, 2013] TEM images shows the spherical to cubic with an average 25 nm. The similar report shows that the TEM image of AgNPs through Bacillus subtilis, produced with a round and slightly rounded shapes with 2 to 20 nm in size [Alsamhary, 2020].

The similar study reported for UV–Vis spectroscopy, a sharp peak at 400–450 nm in synthesis of AgNPs from Pseudoduganella eburnea MAHUQ-39 [Huq, 2020]. In another report, marine algae, an absorbance peak at 445 nm [Bhuyar et al., 2020]. Mostly, SPR band of Ag appearing peak at 420 nm to 445 nm. These reports are in accordance with the current results.

The size and shape of the nanoparticles and the dielectric properties of surrounding medium determines the strength of the SPR. Also, the optical properties of AgNPs change, as a result of particles aggregation. Furthermore, the conduction of electrons near each particle surface becomes delocalized and shared by particles nearby [Das et al., 2021; Vrandečić et al., 2022].

The current study results of antimicrobial properties of bacteria mediated synthesis of AgNPs have a perfect matching with previous studies. Marine bacteria (Planomicrobium sp.) mediated AgNPs exhibited a strong antibacterial activity against B. subtilis [Rajeshkumar and Malarkodi, 2014; Zhao et al., 2022]. Several studies are concentration dependent antimicrobial activities of AgNPs [Saleh et al, 2020; Baker et al., 2005]. Another study revealed, antimicrobial effect of 13 different pathogens were tested using soil isolated bacteria mediated synthesis of AgNPs. The results exhibit a clear inhibition zone with a higher value by agar well diffusion methods. As well as recorded to effect on MRSA7, MRSA8 [Saeed et al., 2020].

Tamboli and Lee observed the roughness and breakage of cell membrane structures of bacterial cells exposed to AgNPs [Tamboli and Lee, 2013]. The smaller particles have greater level of interaction with bacterial cells, so they have more antibacterial effect compared to larger particles [Rani et al., 2023].

Hashem, et al reported the antifungal efficacy of AgNPs from Aspergillus species against different fungal pathogens such as A. niger, A. terreus, A. flavus, and A. fumigatus. The AgNPs inhibit the growth significantly to the tested organisms [Hashem et al., 2022] Bocate et al. observed that AgNPs imposed a greater damage on fungal cells of A. flavus and A. ochraceus, preventing hyphae elongation and inhibiting the germination of conidial spores [Bocate, et al., 2019]. Rathod et al. reported that the binding of nanoparticles to mycelia depends on the surface area available for interaction [Rathod et al., 2011]. The antifungal effects while using the AgNPs are highly potential as the fungal cell contains full of fiber, starches and sugars which leads to rigid. The smaller size of AgNPs was easily penetrate and inhibit the growth and also save from fungal diseases [Matras et al., 2022].

The cytotoxic effect of AgNPs on cell viability play an important role in antitumor activity, thereby slows down the disease progression [Huq and Akter, 2021]. In general, the percentage of cell death ranged between 14 and 95 % and the highest was recorded at the concentration of 20 µg/mL. It is assumed that the interactions of tumor cells with AgNPs lead to cell wall damage and cell death [Alsalhi et al., 2016]. The cell wall was damaged as a result of the hydrophobic interactions between AgNPs and the cell wall interacted. This makes the dye to enter into the tumor cell from their surroundings. Consequently, the damaged cell or non-viable cells appeared blue, whereas viable cells do not take up the Trypan blue. It is also discovered that AgNPs interact with the cell membrane proteins and generate high level of reactive oxygen species (ROS [Kabir et al., 2020].

5 Conclusions

The current study focused on the fast, ecofriendly and cost effective synthesize of AgNPs from the orange pigmented marine bacteria Planococcus maritimus MBP-2. The synthesized AgNPs an average size 24.9 nm and are showing good antibacterial activity of against P. aeruginosa (11 mm) as compared to other tested microbial strains. The sensible antifungal activities recorded against A. niger (14.33 mm) and A. flavus (11.33 mm). An excellent cytotoxic agent against DLA cells from the different concentration of Planococcus maritimus MBP-2 AgNPs. Based on our observations, this study supports the successful use of marine bacteria as cell factories for the synthesis of stable AgNPs with potent biological activities in various medical and pharmaceutical sectors.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their sincere appreciation to the Researchers Supporting Project Number (RSP2023R398) King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- A systematic review on silver nanoparticles-induced cytotoxicity: Physicochemical properties and perspectives. J. Adv. Res.. 2018;9:1-16.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Dahmash, N.D., Al-Ansari, M,M., Al-Otibi, F.O., Ranjith Singh, A.J.A., 2021. Frankincense, an aromatic medicinal exudate of Boswellia carterii used to mediate silver nanoparticle synthesis: Evaluation of bacterial molecular inhibition and its pathway. J. Drug. Deliv. Sci. Technol. 61, 102337. doi.org/10.1016/j.jddst.2021.102337.

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Pimpinella anisum seeds: antimicrobial activity and cytotoxicity on human neonatal skin stromal cells and colon cancer cells. Int. J. Nanomedicin.. 2016;11:4439-4449.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Eco-friendly synthesis of silver nanoparticles by Bacillus subtilis and their antibacterial activity. Saudi J. Biol. Sci.. 2020;27(8):2185-2191.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and antibacterial properties of silver nanoparticles. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol.. 2005;5:244-249.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis of silver nanoparticles using marine macroalgae Padina sp. and its antibacterial activity towards pathogenic bacteria. Beni-Suef Univ. J. Basic Appl. Sci.. 2020;9:3.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antifungal activity of silver nanoparticles and simvastatin against toxigenic species of Aspergillus. Int. J. Food Microbiol.. 2019;291:79-86.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nanotechnological applications in medicine. Anal. Biotechnol.. 2007;18:26-30.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Photo-mediated optimized synthesis of silver nanoparticles using the extracts of outer shell fibre of Cocos nucifera L. fruit and detection of its antioxidant, cytotoxicity and antibacterial potential. Saudi. J. Biol. Sci.. 2021;28(1):980-987.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial and cytotoxicity effects of synthesized silver nanoparticles from Punica granatum peel extract. Nanoscale Res. Lett.. 2018;13(1):315.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles and its applications. J. Nanotechnol.. 2015;829526

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Microbial nano-factories: synthesis and biomedical applications. Front. Chem.. 2021;9:626834

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- New insights into Brust− Schiffrin metal nanoparticle synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc.. 2010;132:9582-9584.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Preparation of silver nanoparticles and their industrial and biomedical applications: a comprehensive review. Adv. Mater. Sci.. Eng.. 2015;165257

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antifungal Activity of Biosynthesized Silver Nanoparticles (AgNPs) against Aspergilli Causing Aspergillosis: Ultrastructure Study. J. Funct. Biomater.. 2022;13:242.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Pseudoduganella eburnea MAHUQ-39 and their antimicrobial mechanisms investigation against drug resistant human pathogens. Int. J. Mol. Sci.. 2020;21(4):1510.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bacterial mediated rapid and facile synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their antimicrobial efficacy against pathogenic microorganisms. Materials.. 2021;14:2615.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis of silver nanoparticles: chemical, physical and biological methods. Res. Pharm. Sci.. 2014;9(6):385-406. PMID: 26339255

- [Google Scholar]

- Anticancer efficacy of biogenic silver nanoparticles in vitro. SN Appl. Sci.. 2020;2:1111.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Silver-based crystalline nanoparticles, microbially fabricated. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.. 1999;96:13611-13614.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lal, H.M., Uthaman, A., 2021. Thomas, S. Silver Nanoparticle as an Effective Antiviral Agent. In: Polymer Nanocomposites Based on Silver Nanoparticles; Lal, H.M., Thomas, S., Li, T., Maria, H.J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany. pp 247–265.

- Surface properties-dependent antifungal activity of silver nanoparticles. Sci. Rep.. 2022;12:18046.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Biosynthesis, characterization, and evaluation of antibacterial and photocatalytic methylene blue dye degradation activities of silver nanoparticles from Streptomyces tuirus strain. Environ. Res.. 2022;204:112360

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Microbial mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles by lactobacillus plantarum TA4 and its antibacterial and antioxidant activity. Appl. Sci.. 2020;10:6973.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay, K. biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using culture supernatant of Shewanella sp. ARY1 and their antibacterial activity. Int. J. Nanomed.. 2020;15:8295-8310.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, characterization and biomedical application of silver nanoparticles. Materials. 2022;15:427.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Isolation and characterization of novel carotenoid pigment from marine Planococcus maritimus MBP-2 and their biological applications. J. King Saud Univ. Sci.. 2023;35:102872

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles by Conocarpus lancifolius plant extract and their antimicrobial and anticancer activities. Saudi J. Biol. Sci.. 2022;29(1):460-471.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antibiotic assay by agar-well diffusion method. Acta Biol. Med. Exp.. 1990;15:113-115.

- [Google Scholar]

- What factors control the size and shape of silver nanoparticles in the citrate ion reduction method? J. Phys. Chem.. 2004;108:945-951.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pradeep, M., Kachlicki, D.K.P., Mondal, D., Franklin, G., 2022. Uncovering the phytochemical basis and the mechanism of plant extract-mediated eco-friendly synthesis of silver nanoparticles using ultra-performance liquid chromatography coupled with a photodiode array and high-resolution mass spectrometry. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2022 10 (1), 562-571, doi: 10.1021/acssuschemeng.1c06960.

- Characterization of silver nanoparticles synthesized by using marine isolate Streptomyces albidoflavus. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol.. 2012;22(5):614-621.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- In vitro antibacterial activity and mechanism of silver nanoparticles against foodborne pathogens. Bioinorg. Chem. Appl.. 2014;581890

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis of silver nanoparticles by leaf extract of Cucumis melo L. and their in vitro antidiabetic and anticoccidial activities. Molecules. 2023;28:4995.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Biosynthesis of highly stabilized silver nanoparticles by Rhizopus stolonifer and their Anti-fungal efficacy. Int. J. Mol. Clin. Microbiol.. 2011;1:65-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bacterial-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their significant effect against pathogens. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res.. 2020;27:37347-37356.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bio-synthesis of silver nanoparticles from bacteria Klebsiella pneumonia: their characterization and antibacterial studies. J. Phys. Conf. Ser.. 2020;1664:012115

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Green synthesis of metallic nanoparticles and their prospective biotechnological applications: an overview. Biol. Trace Elem. Res.. 2021;199:344-370.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pseudomonas indica-mediated silver nanoparticles: antifungal and antioxidant biogenic tool for suppressing Mucormycosis fungi. J. Fungi.. 2022;8:126.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Shylesh, B., Nair, S.A., 2005. Subramoniam, A. Induction of cell-specific apoptosis and protection from Dalton’s lymphoma challenge in mice by an active fraction from Emilia sonchifolia. Indian J. Pharmacol. 37, 232. doi: 10.4103/0976-500X.99420.

- Size dependent antimicrobial activity of Boerhaavia diffusa leaf mediated silver nanoparticles. J. King Saud Univ. Sci.. 2022;34(5):102096

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antitumor activity of silver nanoparticles in Dalton’s lymphoma ascites tumor model. Int. J. Nanomedicine. 2010;5:753-762.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Biogenesis of antibacterial silver nanoparticles using the endophytic bacterium Bacillus cereus isolated from Garcinia xanthochymus. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed.. 2012;2:953-959.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Phytosynthesis of silver nanoparticles from Jatropha integerrima Jacq. flower extract and their possible applications as antibacterial and antioxidant agent. Saudi. J. Biol. Sci.. 2022;29(2):680-688.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mechanistic antimicrobial approach of extracellularly synthesized silver nanoparticles against gram positive and gram-negative bacteria. J. Hazard. Mater.. 2013;260:878-884.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antibacterial properties of silver nanoparticles synthesized by marine Ochrobactrum sp. Braz. J. Microbiol.. 2014;45:1221-1227.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Green Nanotechnology: Advancement in Phytoformulation Research. Medicines.. 2019;6:39.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The richness and diversity of catalases in bacteria. Front. Microbiol.. 2021;12:645477

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Characteristics of bacterial community in Pelteobagrus fulvidraco integrated multi-trophic aquaculture system. Water. 2022;14:3192.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Appendix A

Supplementary material

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2023.103073.

Appendix A

Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article: