Translate this page into:

Non randomness in spatial distribution in two inland water species malacostracans

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

The benthic crustaceans do not have random spatial distribution under natural conditions, this means that these species can have a determined pattern such as associated or uniform. In this work we studied a non-random spatial pattern in two freshwater malacostracan species, Aegla cholchol (Decapoda) from Cautin river, and Hyalella patagonica (Amphipoda) from Quillelhue lake (38°S, Araucania Region, Chile) respectively. The data revealed that both species have an associated pattern, and negative binomial distribution. These results agree with similar observations for other inland water benthic species from Southern Chilean rivers and streams.

Keywords

Malacostracan

Randomness negative binomial distribution

Spatial distribution

1 Introduction

The macrozoobanthos crustaceans in Chilean Patagonian inland waters have amphipods of the genus Hyalella and decapoda of the genus Aegla and Samastacus (Jara et al., 2006). Many of the studies are oriented to taxonomy (González, 2003; Jara et al., 2006) and the first related to the ecology of these organisms have been restricted primarily to the rivers of central and northern Patagonia (Figueroa et al., 2003, 2007, 2009, 2013; Oyanedel et al., 2008; Córdova et al., 2009; Palma et al., 2009).

The amphipods of Patagonian (51–54°S) Chilean inland waters belong to three species: Hyalella patagonica Cunningham, 1871, H. franciscae González & Wattling, 2003, and H. simplex Schellenberg, 1943 ( González, 2003; Gonzalez and Watling, 2003; De los Ríos-Escalante et al., 2013a, 2013b, 2014a,b). The Aegla genus includes 20 endemic species in Chile distributed between 31 and 45°S, and crayfishes of Family Parastacidae with six species belonging to Parastacus, Samastacus and Virilastacus genus (Jara et al., 2006; De los Ríos-Escalante et al., 2013b; Jara, 2013). The aim of the present study is to analyze the spatial distribution patterns of the key species for Chilean inland waters Hyalella patagonica and Aegla cholchol.

2 Materials and methods

Hyalella patagonica specimens were collected during January 2012 in the littoral zone of Quwillelhue lake (39°34′S; 71°32′W), using a Surber net of 80 μm mesh size, removing submersed vegetation and stones in the sampled quadrant (25 cm × 25 cm) (Dominguez and Fernández, 1999). Individuals of Aegla cholchol were collected in littoral zone of Cautin river, close to Cajón town (38°45′S; 72°40′W) during January 2006, using the same sampling device, removing submersed stones in the sampled quadrant with the opening facing the current of the river (Dominguez and Fernández, 1999). The specimens were preserved with absolute ethanol and then counted at the laboratory.

Variance/mean ratios were calculated to determine if the spatial distribution pattern of the studied populations was associated, uniform or random (Zar, 1999; Fernándes et al., 2003). First, we registered the number of individuals for each sample, and then determined the variance and mean of each sample as a way to determine the spatial pattern for both species. So, if the variance-mean ratio value is 1, the distribution is random; whereas if the variance mean ratio is lower than 1, the distribution is uniform; and finally if the variance mean ratio is greater than 1, the spatial distribution is aggregated (Zar, 1999; Fernándes et al., 2003). After this, data were examined using the Poisson, binomial or negative binomial distributions as appropriate probabilistic models of the spatial distribution patterns results obtained by Variance/mean ratio. If the first analysis denoted associated, uniform and random spatial distribution, a second step analysis was applied with the negative binomial, positive binomial, and Poisson probability distributions, respectively (Fernándes et al., 2003), all these statistical analysis were done using Xlstat software.

3 Results and discussion

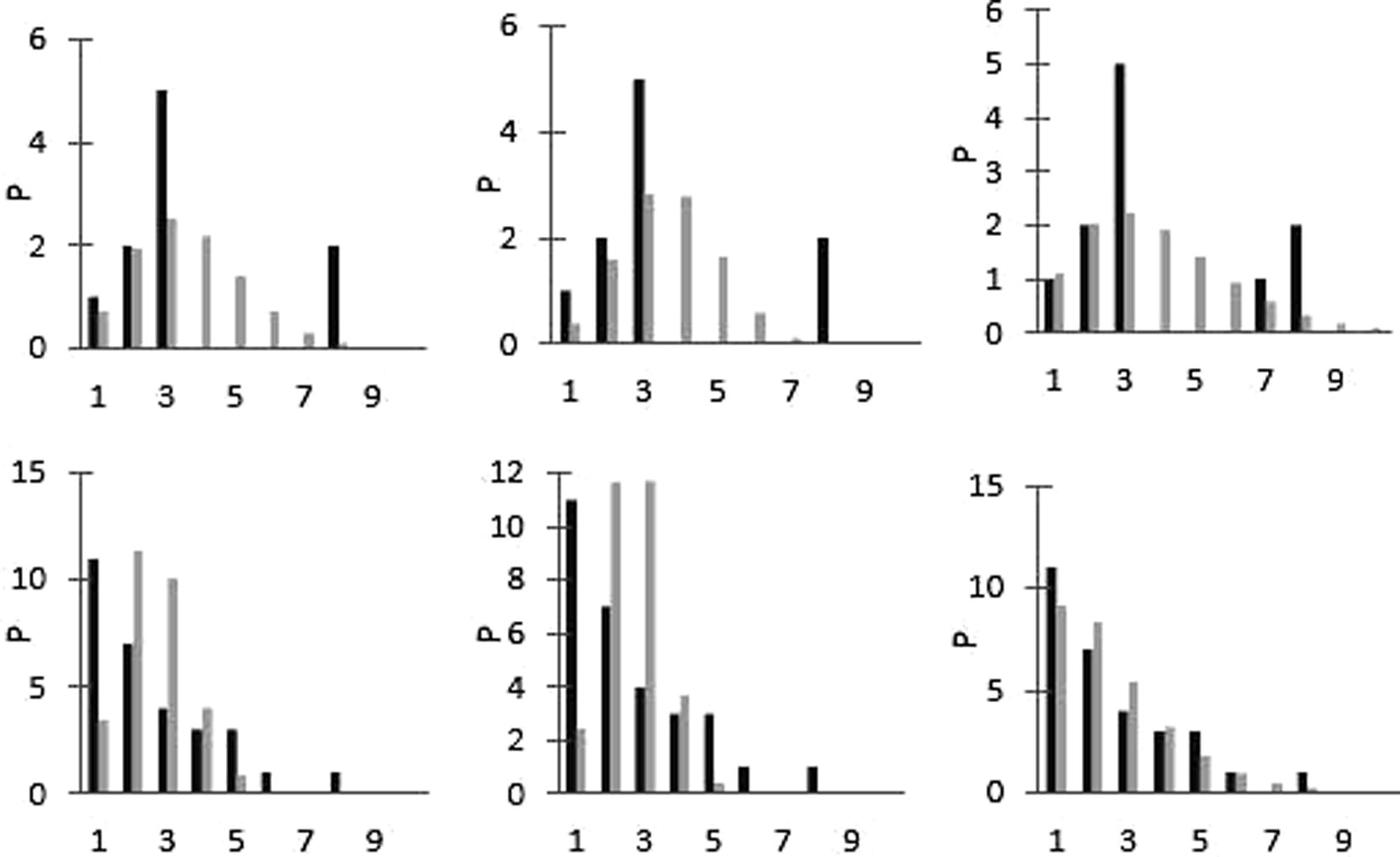

The mean densities observed were 2.909 ind/m2 for Hyalella patagonica and 1.500 ind/m2 for Aegla cholchol (Table 1). The results of the variance mean ratio revealed the aggregated condition of spatial distribution for 2.163 and 3.125 for H. patagonica and H. cholchol respectively (Table 1), nevertheless H. patagonica has not adjusted to the mentioned probabilistic models, whereas A. cholchol has a negative binomial distribution (Table 1; Fig. 1). H. patagonica; A. cholchol.

Density

2.909 + 6.291

1.500 + 2.684

Variance/mean ratio

2.163

3.125

Results of Poisson distribution

c2 observed

3.167

1076.501

c2 table

15.507

15.507

P

<0.001

<0.001

Results of binomial distribution

c2 observed

414.009

4110159.994

c2 table

15.592

15.592

P

<0.001

<0.001

Results of negative binomial distribution

c2 observed

16.008

4.534

c2 table

14.067

14.067

P

<0.001

0.717

Results of spatial distribution: Poisson (left), binomial (centre) and negative binomial (right) for H. patagonica (first row) and A. cholchol (second row). (Black bars: observed frequence; grey bars: expected frequence.)

For both the species, observed densities were similar to those reported for A. rostrata Jara, 1977 (0.0–14.4 ind/m2) and for H. patagonica 0.0–24.0 ind/m2 in a small urban river in Temuco area, Chile (Correa-Araneda et al., 2010) and for A. alacalufi, Jara, 1982 (3 ind/m2). Although, for H. patagonica the observed density was low in comparison to the earlier reported value of 40 ind/m2 in southern Chilean rivers (Oyanedel et al., 2008).

The presence of aggregated pattern for observed taxa would be associated to ecological strategies for optimal and efficient resources utilization and protection against environmental stressors (Gray, 2005; De los Rios-Escalante et al., 2011). In this scenario Aegla species are representative of low polluted zones in rivers and lakes where they feed on dead animal, vegetal particulated matter and benthic organisms (Lara and Moreno, 1995; Figueroa et al., 2003, 2007). Whereas that Hyalella genus is more abundant in zones with more organic matter content in the sediments and moderate organic pollution, it would feed on macrophytes and dead vegetals (De los Rios-Escalante et al., 2011).

Negative binomial distribution has been suggested for explaining associated spatial distributions (Zar, 1999; Fernándes et al., 2003), and it has been applied in studies for terrestrial insects (Maruyama et al., 2002; Fernándes et al., 2003), ectocommensals (De los Ríos-Escalante et al., 2014), parasites (Shaw et al., 1998; Peña-Rehbein and De los Ríos-Escalante, 2012; Peña-Rehbein et al., 2013), and macrozoobenthos (Gray, 2005; Noro and Buckup, 2010; De los Rios-Escalante et al., 2011; De los Ríos-Escalante and Mansilla, 2017; Elliot, 1999). The negative binomial distribution is not an obligatory condition for aggregated spatial pattern, a possible cause would be strong environmental heterogeneity (Benton et al., 2002; De los Rios-Escalante et al., 2011).

Acknowledgements

The present study was funded by the project DG-UCT 2007-01 and the Environmental School Sciences of the Catholic University of Temuco. Valuable comments and suggestions by MI are acknowledged.

References

- The population response to environmental noise: population size, variance and correlation in an experimental system. J. Anim. Ecol.. 2002;71:320-332.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluación de la calidad de las aguas del estero Limache (Chile Central), mediante bioindicadores y bioensayos. Latin Am. J. Aquat. Res.. 2009;37:199-209.

- [Google Scholar]

- Amphipoda and decapoda as potential bioindicators of water quality in an urban stream (38° S, Temuco, Chile) Crustaceana. 2010;83:897-902.

- [Google Scholar]

- Spatial patterns of Pisidium chilense (Mollusca, Bivalvia) and Hyalella patagonica (Crustacea, Amphipoda) in an unpolluted stream in Navarino island (54° S, Cape Horn Biosphere Reserve) J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2017;29:28-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- The presence of the genus Hyalella (Smith, 1875) in water bodies near to Puerto Williams (Cape Horn BiosphereReserve, 54° S, Chile) (Crustacea, Amphipoda) Pan-Am. J. Aquat. Sci.. 2011;6:273-279.

- [Google Scholar]

- Probabilistic model for understand the presence of Temnocephala chilensis (Moquin-Tandom 1846) (Platyhelminthes: Temnocephalidae) on adults of a population of Parastacus pugnax (Poeppig 1835) (Decapoda: Parastacidae) in southern Chile. Gayana. 2014;78:81-84.

- [Google Scholar]

- Zoogeography of Chilean inland water crustaceans. Latin Am. J. Aquat. Res.. 2013;41:846-853.

- [Google Scholar]

- Inland water microcrustacean assemblages in an altitudinal gradient in Aysen región (46° S, Patagonia, Chile) Brazilian Journal of Biology. 2014;74:8-15.

- [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez E., Fernández H.R., eds. Macroinvertebrados bentónicos sudamericanos. Sistemática y Biología. Tucumán, Argentina: Fundación Miguel Lillo; 1999. p. :1-654.

- Some methods for the statistical analysis of benthic invertberates. Frehswat. Biol. Assoc. Sci. Publ.. 1983;25:1-157.

- [Google Scholar]

- Distribucao espacial de Alabama argillacea (Hubner) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) Neotropical Entomol.. 2003;32:107-115.

- [Google Scholar]

- Macroinvertebrados bentónicos como indicadores de calidad de agua de ríos del sur de Chile. Rev. Chil. Hist. Nat.. 2003;76:275-285.

- [Google Scholar]

- Análisis comparativo de índices bióticos utilizados en la evaluación de la calidad de las aguas en un río mediterráneo de Chile: río Chillán, VIII Región. Rev. Chil. Hist. Nat.. 2007;80:225-242.

- [Google Scholar]

- Caracterización ecológica de humedales de la zona semiárida en Chile central. Gayana. 2009;73:76-94.

- [Google Scholar]

- Freshwater biodiversity and conservation in mediterranean climate streams of Chile. Hydrobiologia. 2013;719:269-289.

- [Google Scholar]

- The freshwater amphipods Hyalella Smith, 1874, in Chile (Crustacea, Amphipoda) Rev. Chil. Hist. Nat.. 2003;76:623-637.

- [Google Scholar]

- A new species of Hyalella from the Patagonia, Chile, with redescription of H. simplex Schellenberg, 1943 (Crustacea: Amphipoda) J. Nat. Hist.. 2003;37:2077-2094.

- [Google Scholar]

- Selecting a distributional assumption for modeling relative densities of benthic macroinvertebrates. Ecol. Model.. 2005;185:1-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Estados de conocimiento de los malacostracos dulceacuícolas. Gayana. 2006;70:40-49.

- [Google Scholar]

- A checklist of the Chilean species of the genus Aegla (Decapoda, Anomura, Aeglidae) Crustaceana. 2013;86:1433-1440.

- [Google Scholar]

- Efectos de la depredación de Aegla abtao (Crustacea, Aeglidae) sobre la distribución espacial y abundancia de Diplodon chilensis (Bivalvia), Hyriidae) en el lago Panguipulli, Chile. Rev. Chil. Hist. Nat.. 1995;68:123-129.

- [Google Scholar]

- Distribucao espacial de Dilobopterus costalimai Young (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae) em Cistros na regiao de Tamaringa SP. Neotrop. Entomol.. 2002;31:034-040.

- [Google Scholar]

- The burrows of Parastacus defossus (Decapoda: Parastacidae), a fossorial freshwater crayfish from southern Brazil. Zoologia (Curitiba). 2010;27:341346.

- [Google Scholar]

- Patrones de distribución espacial de los macroinvertebrados bentónicos de la cuenca del río Aysén (Patagonia chilena) Gayana. 2008;72:241-257.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluación de rivera y hábitat fluvial a través de los índices QBR e IHF. Gayana. 2009;73:57-63.

- [Google Scholar]

- Use of negative binomial distribution to describe the presence of Anisakis in Thyrsites atun. Rev. Brasil. Parasitol. Veter.. 2012;21:78-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- Use of a negative binomial distribution to describe the presence of Sphyrion laevigatum in Genypterus blacodes. Rev. Brasil. Parasitol. Veter.. 2013;22:602-604.

- [Google Scholar]

- Patterns of macroparasite aggregation in wildlife host populations. Parasitology. 1998;117:597-610.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biostatistical analysis. New Jersey: Prentice Hall; 1999. pp. 1–663