Translate this page into:

Development of quick and accurate methods for identifying human pathogenic yeast by targeting the phospholipase B gene, topoisomerase II gene, Candida drug resistance gene, and species-specific ITS 2

*Corresponding author: E-mail address: drzahid.casvab@um.uob.edu.pk (M. Mustafa)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

Abstract

Candida species are a major cause of mortality in immune-compromised patients with head and neck cancer. The early detection and classification of Candida species isolated from clinical samples is crucial because of their diverse antifungal resistance patterns. This study aimed to innovate a quick and species-specific PCR-based approach for identifying Candida and pink yeast in clinical specimens. The newly developed method targets Phospholipase B (PLB), Topoisomerase II, Candida Drug Resistance (CDR) genes, and species-specific Internal transcribed spacer (ITS2) genes as novel targets. In this study, we used human pathogenic yeast species identified using universal ITS1 and 4 primers, followed by DNA sequencing. A fast and species-specific molecular technique based on PCR was carried out to identify the eight most common isolated yeast species from clinical specimens, including Candida dubliniensis, C. tropicalis, C. albicans, C. parapsilosis, C. lusitaniae, C. glabrata, Cryptococcus gattii, and Rhodotorula mucilaginosa primers targeting phospholipase B (PLB), topoisomerase II, Candida Drug Resistance (CDR) and Species-specific ITS2 region. The newly developed primers successfully amplified the targeted regions by PCR, resulting in the identification of the selected species. No cross-amplification was observed in yeast or other Candida species. The amplified products were subsequently confirmed using DNA Sanger sequencing. The study suggests that species-specific primers for several genes provide a novel approach for identifying and detecting yeast species with medicinal significance in clinical samples.

Keywords

Candida Drug Resistance (CDR) gene

Internal Transcribe Spacer (ITS2)

Isomerase II gene

Phospholipase B (PLB) gene

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

Rapid detection

1. Introduction

In recent years, fungal infections, particularly Candida, Aspergillus, Mucor, and Cryptococcus species, have significantly increased in the majority of immunocompromised patients, mostly cancer patients (Tufa et al., 2023; Gnat et al., 2021; Shariati et al., 2020). Compared to others, Candida species mostly cause yeast infections. Nevertheless, their clinical manifestations and prognoses may vary. Candidiasis, a fungal infection caused by Candida species, is a significant threat to human health. Notably, Candida albicans is the predominant etiological agent responsible for invasive yeast infections (Pappas et al., 2018; Lass-Flörl et al., 2024). However, recent epidemiological studies have revealed an alarming surge in candidiasis cases attributed to non-albicans Candida species, including C. guilliermondii, C. parapsilosis, C. krusei, C. tropicalis, C. kefyr, C. glabrata, and C. dubliniensis, particularly in immunocompromised individuals, like those with cancer (Arafa et al., 2023; Aydemir et al., 2017; Taei et al., 2019). Another form of yeast infection caused by Rhodotorula species has emerged in patients with cancer. Although Rhodotorula species, including R. minuta, R. glutinis, and R. mucilaginosa, have been identified as human pathogens, members of the Rhodotorula genus were previously believed to be non-pathogenic. The majority of the infections were caused by fungemia, that is, the presence of yeast infection in the blood (Miglietta et al., 2015; FaqeAbdulla, 2024). Fungal diseases are responsible for an estimated 1.6 million deaths per year, and more than a billion individuals suffer from serious fungal diseases (Almeida et al., 2019; Rokas, 2022).

Several approaches for the rapid and accurate identification of yeasts have been developed. Numerous yeast identification tests are available, ranging from traditional methods to molecular methods. Clinical microbiology laboratories face significant challenges in selecting an accurate, cost-effective, easy-to-interpret, and reasonably fast yeast identification system (Bharathi, 2018). Fungal identification primarily relies on morphological and physiological characteristics. However, the distinctive properties of fungi make morphological identification and classification difficult (Fajarningsih, 2016; Arifah et al., 2023). Furthermore, identification processes require specialized knowledge, can yield misleading results, and are typically time-consuming, delaying an accurate diagnosis. Alternative diagnostic methods that directly detect diagnostic molecules are becoming increasingly popular (Gabaldón, 2019).

Specific primers derived from genome sequences were created, and their specificities were verified by PCR-based identification, enabling quick species-level detection of Candida (Harmal et al., 2013), and a single, targeted DNA fragment from the pertinent genomic DNA of the Candida species was amplified by each primer (Kanbe et al., 2002).

Phospholipases (PLB) are enzymes found in most living organisms, particularly eukaryotes (Cerminati et al., 2019). They help balance membrane contents, obtain nutrients, and produce bioactive molecules (Köhler et al., 2006; Giriraju et al., 2023). The PLB gene of Candida species was selected as the place to make primers for Candida species because it is a new target, and the sequences of Candida species vary greatly. This resulted in a few unique sequences for each species of Candida, making it possible to create primers for each species that target the unique sequences of the PLB gene (Harmal et al., 2013).

DNA topoisomerases are enzymes that catalyze topological changes in DNA by reuniting double-helical strands. Type II enzymes simultaneously cut and seal both strands, eliminating twists and knots ( Matias-Barrios, & Dong, 2023 ;Uusküla-Reimand & Wilson, 2022; Wang, 1996). They play important roles in gene expression, recombination, repair, and DNA replication. DNA topoisomerases are potential therapeutic targets. However, research on fungal DNA topoisomerase II is limited (Keller et al., 1997; Madabhushi, 2018). The nucleotide sequences of the gene in Aspergillus nidulans and Candida species have been determined (Kato et al., 2001). This gene is a useful target to research phylogenetic links between fungal species, evolution of fungal genes, and the molecular identification of several fungal species (Kanbe et al., 2002).

Candida species are resistant to clinical fungicides because of their multidrug efflux pumps, which help move drugs out of cells (Krishnasamy et al., 2018). This resistance is linked to the growth of gene families and increased gene expression. Specifically, ATP-Binding Cassette (ABC) and Major Facilitator Superfamily (MFS) transporters are involved; notably, CDR1 had the highest expression. CDR1 is an ABC transporter with the highest basal expression level among the ABC transporters. The Candida drug resistance (CDR) genes, including CDR1, facilitate the transport of azoles and other compounds. (de Oliveira Santos et al., 2018; Rybak et al., 2019). The foundation for the use of ribosomal DNA (rDNA) genes for the identification of fungal species was established by identifying conserved areas in 5.8S and 28S rDNA that permit the amplification of the Internal transcribed spacer (ITS2)c region between these two genes (Keller et al., 2009). Recent research suggests that sequence variations and sizes of fungal ITS2 areas are relevant for quick identification of therapeutically important fungi (Turenne et al., 1999). PCR using fungus-specific primers that target conserved regions of 5.8S and 28S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) caused the species-specific ITS2 regions, whose amplicon lengths differed, to be amplified (Turenne et al., 1999).

This study involved the development of a PCR technique tailored to specific species. The technique targets specific genes, such as phospholipases, DNA topoisomerases, Candida drug resistance, and ITS2 found in yeast species. This enabled the identification and differentiation of the most prevalent, clinically, and medically important Candida and pink yeast strains.

2. Material and methods

2.1 Source of fungal species

In this study, previously identified yeast species in patients with head and neck cancer were used. The specificity of the designed primers was verified in this study using a variety of identified cultures of yeast species, comprising C. albicans OR116194, C. glabrata OR095859, C. lusitaniae OR078628, C. dubliniensis OR342710, C. parapsilosis OR105646, C. tropicalis OR091337, Cryptococcus gattii OR192923, and Rhodotrula mucilaginosa OR105622.

2.2 Culture of fungal species

Culture tests were performed on yeast and mold agar media (Wickerham 1951). Yeast cultures were aseptically inoculated on YM agar using a sterile cotton swab, incubated for 48-96 hours at 37°C in a low-temperature incubator, and then examined and purified.

2.3 DNA extraction

The standard cetyl trimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) technique was used to isolate genomic DNA (Lee et al., 1988; Wu et al., 2001). The cell walls of the fungal mycelia were disrupted using CTAB-containing crushed glass powder. After adding the CTAB extraction buffer and incubating at 65°C, purification with phenol, chloroform, and isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) was performed. This was followed by precipitation with isopropanol. After resuspension in 1X TE buffer, the DNA pellet was kept cold -20°C.

2.4 Universal PCR amplification

Universal ITS primers were used to amplify the conserved region of yeast genomic DNA. The reverse and forward sequences of ITS1 and ITS4 were 5’-TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG-3’ and 5’-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3’, respectively.

PCR reaction mixture (25 µL) was prepared using 1 µL of each ITS1 and ITS4 primers, 2 µL template DNA, and 21 µL Master mix was added to the reaction mixture. The master mix contained MgCl2, Buffer, dNTPs, Taq polymerase, and PCR water. The PCR program included 35 cycles, each lasting for six minutes at 95°C for denaturation. PCR conditions for all were denaturation at 95°C for 40 s, annealing at 59°C for 40 s, and an extension at 72°C for 1 min. The final extension was set for 6 min at 72°C, after which the temperature was maintained at 4 °C until the samples were withdrawn from the thermal cycler. The PCR products were then examined by gel electrophoresis, and the CLINX Science Instruments Gel Doc System was used to visualize the results.

2.5 Species-specific identification of yeasts

Nucleotide sequences of the PLB, topoisomerase II, CDR genes, and species-specific ITS2 regions were used in this study for specific identification of pink yeasts and Candida species. The sequences of genes were retrieved from National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Gene Bank for, C. glabrata, C. lusitaniae, C. gattii, C. albicans, C. parapsilosis, C. tropicalis, C. dubliniensis, and R. mucilaginosa. Species-specific primers were designed using Primer 3 online tools and in silico PCR was performed to check their accuracy for targeted amplification.

The PLB gene in Candida species has been used for species-specific identification owing to its high variability (Harmal et al., 2013). Primers targeting this gene were synthesized for C. parapsilosis, C. gattii, C. albicans, C. glabrata, C. tropicalis, C. lusitaniae, and C. dubliniensis. The DNA topoisomerase II-encoding gene was chosen because of its highly homologous and species-specific sequence. Primers were developed for C. parapsilosis, C. glabrata, and C. lusitaniae, and PCR was used to verify the presence of CDR genes in Candida species. ITS regions were used to identify fungal species, but the amplified PCR products were sequenced to determine the species.

The PCR experiment involved a 20 µL volume of the Master Mix, primers, and template DNA. The mixture underwent 35 cycles of denaturation, annealing, and extension in a thermal cycler. Template-free reactions were used as negative controls. Each PCR product was combined with 6x loading dye and loaded onto 2% agarose gel. To evaluate and determine the PCR product size, the first lane was filled with a 100 bp DNA marker. The gel was run at 110 V for 30 min, and PCR products were visualized using a Gel Documentation system. The species-specific primers, their annealing temperatures, and PCR product sizes have been listed in Table 1.

| Yeast species | Primer name | Primer sequence (5’-3’) | Annealing temperature | Polymerase chain reaction product size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. glabrata |

CG(PLB) CG(TOP) CG(CDR) |

GCATGTGCCATCATGAAAAG CCTCTGGGTTGATGAAGGAA TCTTCCGGTCTTGCTTCAGT TTCCTGCACAAGCAAGTGTC ACGGTACCAAGCCATACGAG GAACACTGGGGTGGTCAAGT |

58.2°C 60.5°C 62.3oC |

160bp 215bp 188bp |

| C. parapsilosis |

CP(PLB) CP(TOP) CP(CDR) |

AACACGTTGTGGCAAATTCA TTGGAAACCGTTTTGAGACC CTGCGTATCAAGGGTCAGGT CAGCGTTCTTTGCAATTTGA CTTCCGGTCACTTGAATGGT TCCTCCATAATGGGCTTGTC |

57.58oC 58.6°C 60.1oC |

234bP 220bp 221bp |

| C. tropicalis |

CT(PLB) CT(CDR) |

ATGTTGAATGGTGCTGGTCA TTCCAACCACCTGGATTCAT GATCGGGAATTGCTCACACT AATTTGCAGCCGTCAAAAAC |

59.2°C 57.8oC |

230bp 163bp |

| C. lusitaniae |

CL(PLB) CL(TOP) |

GCCGATAAAATCTCCGATGA TCCTCCGGAGAATGCAATAC CAAGGACCACCGTTTCTGTT CAGACAGCGCCTTATTCTCC |

58.1°C 60.4°C |

177bp 219bp |

| C. dubliniensis |

CD(PLB) CD(CDR) |

CTCAAGGCTTGTGGGAACTC TGGTTACATCGGACCACAAA TCTCACGTTGCCAAACAATC CAGCAAAGAACATGGAAGCA |

60.3°C 57.6oC |

225bp 241bp |

| C. albicans | CA(PLB) |

GGCTCATCTGGTGGAACATT TGGTACCATGAACTGCCTGA |

57°C | 164bp |

| Cryptococcus gattii | CRG(PLB) |

GCTGCCTTAGGAAATGCAAG GACTACCAAACGCCCAAGAA |

59.1°C | 205bp |

| Rhodotorula mucilaginosa | RM(ITS2) |

ACTCTCGCAAGAGAGCGAAC GGTGCGTTCAAAGATTCGAT |

59.3°C | 187bp |

2.6 DNA sequencing

Commercial Sanger sequencing for DNA was performed by the Gene Janch DNA sequencing service, Karachi. PCR-amplified products of each yeast species were sequenced and BLAST in NCBI was used for confirmation of species identification.

3. Results

Amplicons of different sizes were produced during the PCR process because of the variation in length between the ITS 1 and ITS regions of distinct Candida and pink species. The PCR products of, C. tropicalis, C. lusitaniae, C. albicans C. glabrata, C. dubliniensis, C. parapsilosis, C. gattii, and R.mucilaginosa generated using ITS 1and ITS 4 universal fungal primers, were roughly 524bp ,377bp, 535bp, 871bp, 540bp, 520bp, 600bp, and 630bp, respectively.

3.1 Phospholipase B gene PCR amplification

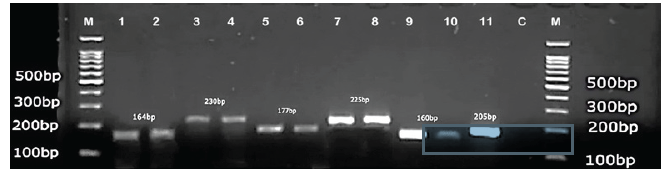

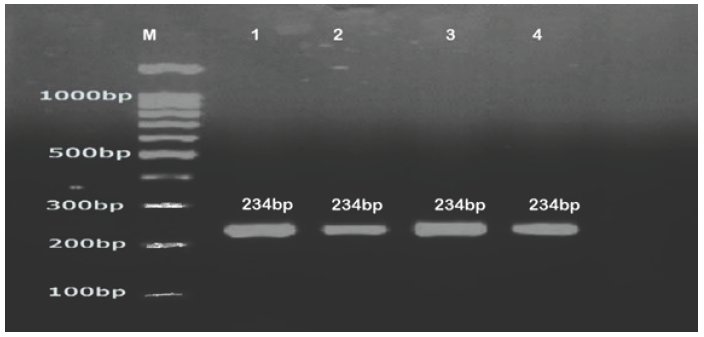

Species-specific primers of six Candida species viz., C. dubliniensis, C. lusitaniae, C. parapsilosis, C. glabrata, C. albicans, C. tropicalis, and C. gattii were designed from a region of the PLB gene using Primer 3 online software tools. Distinct band-size PCR products were produced on a 2% agarose gel by all six Candida species. The amplified PCR bands were observed at, 230bp, 225bp, 234bp, 164bp, 160bp, 177bp, and 205bp and respectively identified as C. tropicalis, C. dubliniensis, C. parapsilosis, C. albicans, C. glabrata, C. lusitaniae, and C. gattii (Figs. 1 and 2).

- DNA ladder 100bp (Transgen Biotech), C. albicans, (1,2): C. tropicalis (3,4) : C. lusitaniae (5,6) : C. dubliniensis (7,8): C. glabrata (9,10), 11: Cryptococcus gattii (11): C: negative control (12) 1 M: DNA molecular marker.

- DNA ladder 100bp (Transgen Biotech), C. parapsilosis (1,2,3,4).

3.2 PCR amplification of topoisomerase II gene

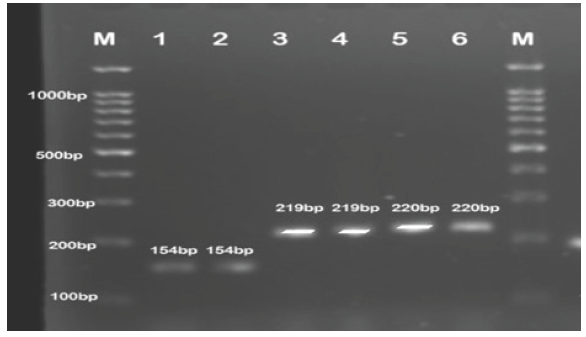

The topoisomerase II gene of Candida spp. has been selected as a novel target for species identification. In this study, primers specific to each species were created for three different Candida species, including Lusitaniae, C. parapsilosis, and C. glabrata, because of variation in their topoisomerase II genes. Visualization on 2% gel showed that C. glabrata produced 154bp pair PCR amplified products, whereas C. parapsilosis gave 220bp and C. lusitaniae gave 219bp PCR products (Fig. 3).

- PCR products of three (3) different Candida species viz., C. glabrata (1,2), C. lusitaniae (3,4), C. parapsilosis (5,6) 100bp DNA Ladder (M). PCR: Polymerase chain reaction.

3.3 PCR Amplification of Candida Drug Resistance (CDR) gene

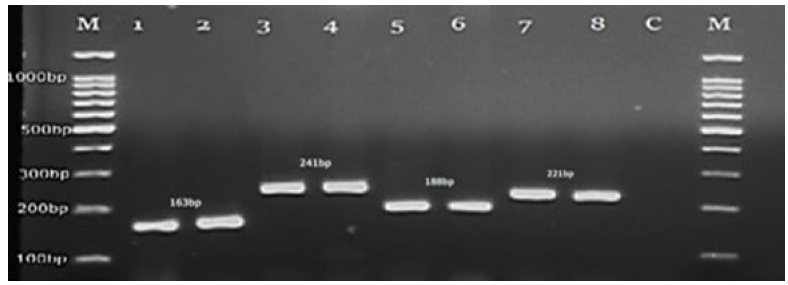

Species-specific primers for the CDR1 gene were also used to specifically identify the four Candida species. When PCR-amplified products of these Candida species were visualized on a 2% gel, C. parapsilosis, C. Tropicalis, C. glabrata, and C. dubliniensis showed characteristic PCR bands of 241bp, 163bp,188bp, and 221bp, identified correctly (Fig. 4).

- DNA marker (M), Candida tropicalis (1,2), C. dubliniensis (3,4), C. glabrata (5,6), C. parapsilosis (7,8), negative control (9) and DNA marker (100bp).

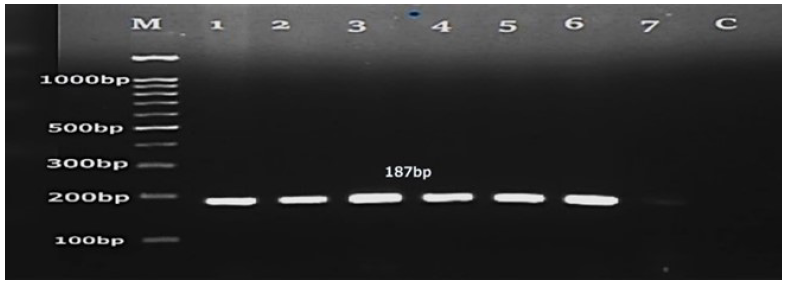

3.4 PCR amplification of ITS2 gene

Species-specific ITS2 primers were designed using Primer 3 online tool for the pink yeast R. mucilaginosa. PCR was performed using template DNA from all 29 pink yeast cultures of R. mucilaginosa and the ITS2 primer set (ITS2F&R). The targeted region of the ITS2 gene of all cultures of R. mucilaginosa was successfully amplified using these species-specific primers and examined using 2% gel electrophoresis. The PCR findings revealed a distinct band of the same size of around 187 base pairs (Fig. 5).

- PCR amplified products of ITS2 gene of Rhodotorula mucilaginosa (lane 1-7) 100bp DNA marker (M) (Transgen Biotech) and negative control (C). PCR: Polymerase chain reaction.

3.5 Sequencing and species-specific PCR verification

The species-specific PCR-amplified product of the yeast species was sent to the Gene Janch, Karachi Sequence Service for sequencing. PCR amplicon sizes of yeast species and the number of cultures produced with different primer sets targeting different target regions/genes have been listed in Table 2. The DNA sequence and chromatogram were edited using BioEdit software. This sequence was then subjected to BLAST in the NCBI reference sequence database for the identification of species.

| No. | Yeast spp. | PCR amplicon sizes (bp) of various yeast species using different primers* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Universal primers | PLB | TOPO II | CDR | ITS 2 | ||

| 1. | Candida albicans | 535 | 164 | - | - | - |

| 2. | C. dubliniensis | 540 | 225 | - | 241 | - |

| 3. | C. glabrata | 871 | 160 | 154 | 188 | - |

| 4. | C. lusitaniae | 377 | 177 | 219 | - | - |

| 5. | C. parapsilosis | 520 | 234 | 220 | 221 | - |

| 6. | C. tropicalis | 524 | 230 | - | 163 | - |

| 7. | Cryptococcus gatii | 600 | 205 | - | - | - |

| 8. | Rhodotorula mucilaginosa | 630 | - | - | - | 187 |

PLB: Phospholipase B gene, TOPOII: Topoisomerase II gene, CDR: Candida drug resistance gene; ITS2: Internal transcribed spacer 2. PCR: Polymerase chain reaction.

4. Discussion

Fungal infections can cause a range of symptoms from mild superficial to life-threatening invasive ones. They cause diseases in immunocompromised individuals such as those with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), cancer, diabetes, transplant, or immunosuppression, such as those receiving chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or immunosuppressive drugs. Effective detection and treatment of high-risk populations are crucial to prevent most deaths (Bongomin et al., 2017; Pathakumari et al., 2020). We created a PCR test to detect and identify the most clinically significant yeast species through species-specific amplification of target genes.

Phospholipases are enzymes found in most living organisms, including eukaryotes, that help maintain the membrane balance, obtain nutrients, and produce bioactive compounds (Aloulou et al., 2018; Köhler et al., 2006). Unlike rRNA genes, PLB genes contain limited variable areas (Harmal et al., 2013) and can therefore be used for specific identification. Because of the significant sequence variability between Candida species, PLB was chosen as the locus for designing Candida species-specific primers. Consequently, this yielded distinct and exclusive sequences for each Candida species, facilitating the development of primers that specifically target individual sequences of the PLB gene (Harmal et al., 2013). Species-specific primers were designed to amplify specific regions of PLB genes for the identification of six Candida spp. and C. gattii. All designed primers successfully amplified the target and specific regions. The product sizes were exactly the same as the predicted sizes, and Candida species, that is, C. albicans (164bp), C. glabrata (160bp), C. lusitaniae (177bp), C. dubliniensis (225bp), C. parapsilosis (234bp), C. tropicalis (230bp), and Cryptococcus gattii (205bp) were correctly identified, corroborating the observations of Harmal et al. (2013) and Pfaller et al. (2010).

DNA topoisomerases catalyze topological changes in DNA by breaking and reuniting double-helical strands (Wang, 1996). These drugs are crucial therapeutic targets. However, few studies have focused on fungal DNA topoisomerase II (Keller et al., 1997). Phylogenetic relationships and characteristics of Candida species have been revealed through isolation and sequencing of their DNA topoisomerase II genes. This gene is crucial for understanding fungal gene evolution and the molecular identification of multiple species (Kato et al., 2001).

To analyze fungal DNA topoisomerase II genes for phylogenetic studies and patient-infecting fungal species, researchers have identified Aspergillus nidulans and numerous Candida species (Kanbe et al., 2002; Kato et al., 2001). The DNA topoisomerase II-encoding gene was selected as the target because it is present in all organisms and has a sequence that is highly similar and unique to each species (Al-Tekreeti et al., 2018; Kanbe et al., 2002). In this experiment we designed primers for three Candida species, C. glabrata, C. lusitaniae, and C. parapsilosis, based on variation in their topoisomerase II genes. Results showed C. glabrata as producing 154bp PCR products, while C. parapsilosis produced 220bp and C. lusitaniae produced 219bp.

Candida species develop resistance to clinical fungicides owing to multidrug efflux pumps, which help them move drugs out of their cells. This resistance can occur because of gene family growth or increased expression (Morschhäuser et al., 2007). Five CDR genes, including CDR1, have been identified in Candida spp. to transport azoles and other drugs, such as cycloheximide and chloramphenicol (Maras et al., 2021). CDR genes have been used in drug expression testing; however, their use for yeast species identification through PCR amplification remains limited. We also used species-specific primers for the CDR1 gene to identify four Candida species, including C. tropicalis, C. Dubliniensis, C. parapsilosis, and C. glabrata. The PCR bands for these Candida spp. were recorded at 163bp,221bp, 241bp, and 188bp, respectively, as expected.

rDNA genes were used to specifically identify fungal species by amplification of the ITS2 region between 5.8S and 28S rDNA (James et al. 1996). ITS2 regions specific to a species are amplified by PCR using primers specific to fungi, and amplicon length varies (Turenne et al., 1999). In the present study, species-specific ITS2 primers were created for the pink yeast R. mucilaginosa (rubra). The targeted region of the ITS2 gene was successfully amplified in all R. mucilaginosa cultures and 187bp PCR products were resolved using 2% agarose gel electrophoresis and observed under UV light.

Fungal infections can range from mild superficial infections to life-threatening invasive ones, causing disease in immunocompromised individuals like those with HIV, cancer, diabetes, transplant, or immunosuppressed such as those receiving chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or using immune suppressive drugs. Effective detection and treatment of high-risk populations are crucial to prevent most deaths (Bongomin et al., 2017; Pathakumari et al., 2020).

5. Conclusions

The recent outcome has encouraged us to take on a new molecular technique development for the identification and discrimination of other medically significant human fungal infections, in addition to Candida species. Species-specific primers were discovered to be a more efficient, rapid, and accurate molecular approach for the identification of yeast species, thereby eliminating the necessity for time-consuming and labour-intensive DNA sequencing methodologies. Species-specific PCR is a versatile tool for quickly identifying a broad range of pathogenic microorganisms at the species level with the ability to add newly developed primers to other medically important human pathogens.

Acknowledgments

This research work was performed at Balochistan University of IT, Engineering and Management Sciences, which is highly acknowledged. This research work was not directly supported or financed by any national or international funding agency.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Ayisha Hafeez: Formal analysis, Data curation, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft. Muhammad Mushtaq: Project administration, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision. Muhammad Hanif: Data curation, Investigation, Visualization. Haleema Saadia: Formal analysis, Investigation. Kaleemullah Kakar: Formal analysis, Investigation. Hira Ejaz: Methodology, Software, Visualization. Syed Moeezullah: Methodology, Writing. Sajjad Karim: Software, Writing – review & editing. Peter Natesan Pushparaj: Software, Writing – review & editing. Mohammad Zahid Mustafa: Project administration, Writing – review & editing. Mahmood Rasool: Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Data availability

All data are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding authors.

Declaration of Generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

References

- Molecular identification of clinical Candida isolates by simple and randomly amplified polymorphic DNA-PCR. Arab. J. Sci. Eng.. 2018;43:163-70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13369-017-2762-1

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The still underestimated problem of fungal diseases worldwide. Front. Microbiol.. 2019;10:214. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.00214

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Phospholipases: An overview. Methods Mol. Biol.. 2018;1835:69-105. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-8672-9_3

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candida diagnostic techniques: A review. J. Umm Al-Qura Uni. App. Sci.. 2023;9:360-77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43994-023-00049-2

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Molecular and morphological characterization of fungi isolated from nutmeg (Myristica fragrans) in North Sulawesi, Indonesia. Biodiversitas Journal of Biological Diversity 2023:24. https://doi.org/10.13057/biodiv/d240151

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Emerge of non-albicans Candida species; evaluation of Candida species and antifungal susceptibilities according to years. Biomed. Res.. 2017;28:1-6. https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12619/65759

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of chromogenic media with the corn meal agar for speciation of Candida. J. Pure Appl. Microbiol.. 2018;12:1617-22. http://dx.doi.org/10.22207/JPM.12.3.68

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Global and multi-national prevalence of fungal diseases—estimate precision. J. Fungi. 2017;3:57. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof3040057

- [Google Scholar]

- Industrial uses of phospholipases: Current state and future applications. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol.. 2019;103:2571-82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-019-09658-6

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candida infections and therapeutic strategies: Mechanisms of action for traditional and alternative agents. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:1351. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2018.01351

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) as DNA barcoding to identify fungal species: a review. Squalen Bulletin. 2016;11:37-44.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Identification and antifungal susceptibility of rhodotorula muci-laginosa isolated from women patients in Erbil City-Iraq Kurdistan. Revis Bionatura. 2023;8:118. http://dx.doi.org/10.21931/RB/(2023).08.03.118

- [Google Scholar]

- Recent trends in molecular diagnostics of yeast infections: From PCR to NGS. FEMS Microbiol. Rev.. 2019;43:517-47. https://doi.org/10.1093/femsre/fuz015

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Functional role and therapeutic prospects of phospholipases in infectious diseases. In: Phospholipases in Physiology and Pathology. Academic Press; 2023. p. :39-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- A global view on fungal infections in humans and animals: opportunistic infections and microsporidioses. J. Appl. Microbiol.. 2021;131:2095-113. https://doi.org/10.1111/jam.15032

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Identification and differentiation of Candida species using specific polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of the phospholipase B gene. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res.. 2013;7:2159-66. http://dx.doi.org/10.5897/AJMR(2013).2501

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Use of an rRNA internal transcribed spacer region to distinguish phylogenetically closely related species of the genera Zygosaccharomyces and Torulaspora. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol.. 1996;46:189-94. https://doi.org/10.1099/00207713-46-1-189

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- PCR‐based identification of pathogenic Candida species using primer mixes specific to Candida DNA topoisomerase II genes. Yeast. 2002;19:973-89. https://doi.org/10.1002/yea.892

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phylogenetic relationship and mode of evolution of yeast DNA topoisomerase II gene in the pathogenic candida species. Gene. 2001;272:275-81. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00526-1

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- 5.8 S-28S rRNA interaction and HMM-based ITS2 annotation. Gene. 2009;430:50-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gene.2008.10.012

- [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molecular cloning and expression of the Candida albicans TOP2 gene allows study of fungal DNA topoisomerase II inhibitors in yeast. Biochem. J.. 1997;324:329-39. https://doi.org/10.1042/bj3240329

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phospholipase A2 and phospholipase B activities in fungi. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2006;1761:1391-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.09.011

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Molecular mechanisms of antifungal drug resistance in Candida species. J. Clin. Diagn. Res.. 2018;12:DE01-DE06. http://dx.doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/(2018)/36218.11961

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Invasive candidiasis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 2024;10:20. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-024-00503-3

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- A rapid, high yield mini-prep method for isolation of total genomic DNA from fungi. Fungal Genet. Newsl.. 1988;25:23-4. https://doi.org/10.4148/1941-4765.1531

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The roles of DNA topoisomerase IIβ in transcription. Int. J. Mol. Sci.. 2018;19:1917. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms(1907)1917

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Hyperexpression of CDRs and HWP1 genes negatively impacts on Candida albicans virulence. PloS One. 2021;16:e0252555. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252555

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- The implication of topoisomerase II inhibitors in synthetic lethality for cancer therapy. Pharmaceuticals. 2023;16:94. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph16010094

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Central venous catheter-related fungemia caused by Rhodotorula glutinis. Med. Mycol. J.. 2015;56:E17-E19. https://doi.org/10.3314/mmj.56.e17

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The transcription factor Mrr1p controls expression of the MDR1 efflux pump and mediates multidrug resistance in Candida albicans. PLoS Pathog.. 2007;3:e164. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.0030164

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Invasive candidiasis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:18026. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2018.26

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Immune defence to invasive fungal infections: A comprehensive review. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2020;130:110550. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110550

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Variation in Candida spp. distribution and antifungal resistance rates among bloodstream infection isolates by patient age: report from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program (2008–2009) Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis.. 2010;68:278-83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2010.06.015

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evolution of the human pathogenic lifestyle in fungi. Nat Microbiol. 2022;7:607-619. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-022-01112-0

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Abrogation of triazole resistance upon deletion of CDR1 in a clinical isolate of candida auris. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.. 2019;63:e00057-19. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.00057-19

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- An overview of the management of the most important invasive fungal infections in patients with blood malignancies. Infect. Drug Resist.. 2020;13:2329-54. https://doi.org/10.2147/idr.s254478

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- An alarming rise of non-albicans candida species and uncommon yeasts in the clinical samples; a combination of various molecular techniques for identification of etiologic agents. BMC Res. Notes. 2019;12:779. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-019-4811-1

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Access to the world health organization-recommended essential diagnostics for invasive fungal infections in critical care and cancer patients in africa: A diagnostic survey. J Infect Public Health. 2023;16:1666-74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiph.2023.08.015

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapid identification of fungi by using the ITS2 genetic region and an automated fluorescent capillary electrophoresis system. J. Clin. Microbiol.. 1999;37:1846-51. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.37.6.1846-1851.1999

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Untangling the roles of TOP2A and TOP2B in transcription and cancer. Sci. Adv.. 2022;8:eadd4920. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.add4920

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- DNA topoisomerases. Annu. Rev. Biochem.. 1996;65:635-92. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.003223

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taxonomy of yeasts. US Department of Agriculture; 1951.

- A simplified method for chromosome DNA preparation from filamentous fungi. Mycosystema 2001:20, 575-577.

- [Google Scholar]